After The Gold Rush

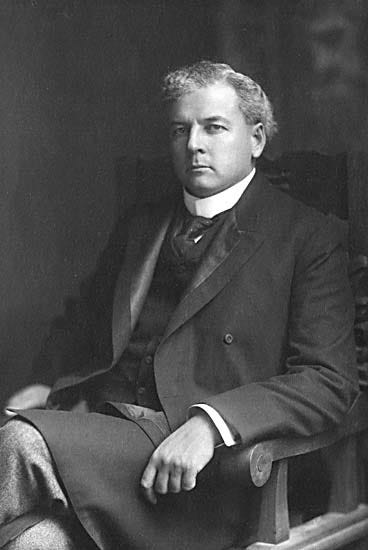

Sir Richard McBride was not your typical politician. Picture him as a blend of a frontier cowboy and a shrewd dealmaker with a knack for bending rules when the stakes were high. He was born in 1870 in New Westminster, British Columbia - just after the gold rush - and a year before BC joined confederation.

I imagine him as Kevin Costner’s John Dutton, the fierce patriarch of Yellowstone. Both men are steely, uncompromising leaders with a deep connection to the land they protect. Like Dutton, McBride operated in a high-stakes environment where decisions carried enormous consequences, and he wasn’t afraid to bend—or break—rules to get results. His bold, unilateral moves mirror Dutton’s tendency to take matters into his own hands when the system falls short.

Both are pragmatic visionaries, understanding that the future of their territory relies on decisive action, often in the face of bureaucracy or external threats. McBride, like Dutton, saw himself as a guardian of his people and their way of life, willing to engage in power plays and calculated risks to ensure the survival and prosperity of his province. Each embodies a blend of tradition and modernity, recognizing the value of legacy while embracing the tools necessary to navigate a rapidly changing world.

Warning: The following segment contains specific types of content, e.g., scenes of war, distressing martial themes, or images of war including machines and men in uniforms]. It may not be suitable for all audiences. Viewer discretion is advised.

You won’t be surprised to learn that BC and various cities and towns are in the process of changing the names of streets and schools named after McBride and removing his images because of his public stance on issues from immigration to voting rights.

If you prefer to bypass the complexities of history and avoid wrestling with the nuance of past eras, you can stop here. Instead, consider this linked article detailing how institutions and landmarks named after Sir Richard McBride are being renamed, a trend reflecting the modern inclination to judge historical figures by today’s standards of social justice.

My view is that while it’s easy in the light of present-day progress and achievement to ridicule and condemn the men, ideas, and customs of any past age, doing so risks losing the wisdom and beauty that history can offer. For those willing to explore these layers, the essay continues.

For others, here’s your alternative text: Sir Richard McBride's Legacy Reexamined.

Take What You Can From Nova Scotia

British Columbia in those days was a land of transformation—a rugged frontier evolving into a vital part of Canada’s national fabric. When the province joined Confederation in 1871, it was a sparsely populated outpost, a Jurassic land of dense rainforests, towering mountains, and isolated communities clinging to the edges of the Pacific.

The gold rush in British Columbia burned bright but brief, leaving behind more than abandoned claims and ghost towns. The Fraser Canyon and Cariboo gold rush—times and places where people could simply pick up gold off the ground and be rich—played out by the 1860s. It marked the end of a chaotic, transient era and the beginning of a more settled, structured society, as the province shifted its focus from the lure of quick riches to the steady promise of industry and infrastructure.

The promise of economic opportunity still hung in the air, but the province’s isolation was its greatest challenge. The Pacific Ocean hemmed it in on one side, while the vast Rocky Mountains loomed as a natural barrier to the rest of Canada.

At 19, McBride headed to Nova Scotia. When he arrived, Halifax was a cauldron of ambition, innovation, and political intrigue. The province’s beating heart, it was a bustling port city alive with the clang of shipyards and the hum of telegraph lines. He arrived in time for the opening of the Public Gardens Bandstand to commemorate Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee, the ornate bandstand in the Halifax Public Gardens designed by Henry Busch, became a central venue for public gatherings and musical performances, enhancing the city's cultural life that saw increased attention to social issues, including public health and education. Nearby institutions such as the School for the Blind in 1871 and the School for the Deaf in 1857 underscored a growing public commitment to addressing the needs of all citizens.

The newspapers were the lifeblood of public discourse, their pages dripping with scandal, satire, and the sharp edge of political rivalry. Premier William Stevens Fielding was in his element, maneuvering through the province's stormy political seas as he pushed for economic reforms and navigated the sour aftertaste of Confederation’s discontent after Nova Scotia was drawn in without any democratic process. Meanwhile, industrial titans like Simon Hugh Holmes wielded influence like hammers, shaping the province’s future with ships, coal, steel, and steam. Part of a Pictou County clan, Holmes in 1858 founded and edited the Pictou Colonial Standard as “a dedicated advocate of the principles of true Conservatism.” The paper and Holmes were advocates of Canadian confederation fighting Joseph Howe’s dominant Anti-Confederates every step of the way to Canada. On the cultural front, Joseph Howe's legacy loomed large, his spirit still sparking debates about the soul of Nova Scotia in regular public meetings and widely read local media that tackled issues of progress, purpose, and prosperity. It was an era of bold dreams and bare-knuckle politics, with every player scrambling to leave their mark on history. McBride soaked it all in.

At the local taverns, inns, and public houses, serving as popular social hubs for Haligonians of the time Alexander Keiths India Pale Ale (IPA) and other traditional British-style ales were in a fierce competition with upstart brewer and mother of nine, Susannah Oland’s October Brown Ales. A competition that university students in the town help battle out to this very day.

By the time McBride graduated from Law School at Dalhousie University in Halifax in the spring of 1893 he was filled with bold ideas about how his new province should work - how it should have hospitals, an education system, and control over its natural resources. He returned to a Vancouver that had transformed from a sleepy logging settlement into a thriving city. Its deep-water port became the lifeblood of the province’s economy, handling goods from around the globe. Steamships lined the docks, bringing immigrants from Europe and Asia, as well as goods that would fuel further industrial growth.

The city’s streets pulsed with the energy of a burgeoning metropolis: electric streetcars, grand hotels, and theaters showcased British Columbia’s growing prosperity. Yet beneath the surface, tensions simmered. Economic disparity, social unrest, and political debates about immigration and resource management shaped the province’s identity.

The People’s Dick

Within five years, at just 28 years old, his conscience would not release him from the problems of the day, McBride entered politics, winning a seat in the British Columbia Legislature in 1898 for the Dewdney district as a member of the Conservative Party. His youthful energy and sharp legal mind quickly distinguished him.

Five years later, in 1903, he was Premier of British Columbia, holding the distinction of being the province’s first native-born leader. He was fiercely patriotic, determined to cement Canada’s position in the British Empire and protect his home province from external threats.

During this time he affiliated as a junior member of Union Solomon Lodge №9, a community-building-oriented lodge of Craft Freemasonry in the city of New Westminster, BC, falling under the jurisdiction of the Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon.

On the sometimes rough streets of BC’s port towns, and in raucous political campaigns Richard McBride was known by his nickname… The People’s Dick.

During his first remarkable decade as Premier, McBride transformed British Columbia from a rugged frontier into a thriving, modern province. He championed the construction of critical railways, including the Pacific Great Eastern, stitching together remote communities and unlocking the province’s vast economic potential. Under his leadership, British Columbia tapped into its wealth of natural resources—forestry, mining, and fisheries—turning these industries into economic cornerstones. McBride also laid the foundation for a better quality of life by establishing schools and hospitals, ensuring the province’s rapid growth was matched by essential public services. Ever mindful of British Columbia’s strategic position, he became a staunch advocate for national defense, playing a key role in the early development of the Royal Canadian Navy. His tenure was a masterclass in building prosperity while safeguarding the province's future.

But it was in 1914, with war clouds looming, that McBride’s flair for audacious action would cross over into an international caper that set the course for Canada through two world wars.

A New Nation, Totally Unprepared for Nationahood

As whispers of war grew louder in Europe, Canada’s military readiness was laughable, particularly on the west coast. The Royal Canadian Navy had just been formed in 1910, but it was still in its infancy. Vancouver and Victoria were bustling ports, ripe for attack, and with Germany's Pacific Squadron prowling the seas, British Columbia seemed defenseless.

It may seem surprising today, but during World War I, the British plan to defend Canada’s west coast included relying on the Royal Japanese Navy. At the time, this strategy made perfect geopolitical sense. Japan was not only an ally under the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902, but it also possessed one of the most powerful and modern navies in the world, fresh from its decisive victory in the Russo-Japanese War.

Meanwhile, Canada’s naval presence on the Pacific was… weak, with only the aging cruiser hilariously named HMCS Rainbow to protect its vast coastline. Britain, focused on the European theater, lacked the resources to safeguard distant territories like British Columbia. The Royal Japanese Navy, already patrolling the Pacific and hunting German ships, was well-positioned to extend its reach. Though unconventional, the arrangement highlighted the strategic pragmatism of the Allies, leveraging Japan’s naval dominance to secure vital Pacific routes and protect vulnerable coastal settlements from potential German attacks.

Germany’s East Asia Squadron, under the command of the formidable Admiral Maximilian von Spee, was a force cloaked in both mystery and menace. Based out of the remote German-controlled port of Tsingtao in China, this fleet was a floating arsenal of cutting-edge cruisers, bristling with heavy guns and manned by battle-hardened sailors. Von Spee's flagship, the Scharnhorst, led a fleet that moved like a phantom across the vast Pacific, appearing suddenly to wreak havoc on Allied shipping lanes before vanishing into the open ocean. The squadron’s reputation was as much for its daring as for its eccentricity—its sailors were known for their precise discipline and peculiar rituals, including planting elaborate gardens on remote atolls where they briefly anchored. Like a leviathan in the depths, Germany’s Pacific fleet loomed large as a dark, unpredictable threat, capable of striking terror across thousands of miles of open sea.

For British Columbians, relying on a distant Imperial Japanese Royal fleet to protect their growing province seemed as unlikely as the HMCS Rainbow taking on the great grey ghost of the German fleet.

Enter McBride. He was no stranger to risk or bold schemes. As Premier, he had championed railway expansions, schools, and hospitals, and fought for provincial autonomy over its natural resources. But now, he faced a more urgent mission: to defend the coast before it was too late.

The Submarine Plot

McBride’s opportunity came through a shadowy figure named Captain Edward E. Sloan, a middleman with connections to the shipyards in Seattle. Sloan knew that two submarines, originally built for Chile, were languishing in the docks. Due to complications with U.S. neutrality laws, the Chilean deal had fallen through — at least for the moment, the Chileans were still in Seattle bargaining with the government for ‘their’ ships. These submarines were up for grabs—but only if the buyer acted fast and discreetly.

McBride didn’t hesitate. Knowing that federal approval would take months or years and Ottawa might balk at the expense, he took matters into his own hands. In a move that would make Clive Cussler proud, McBride authorized the purchase in secret, securing a clandestine nighttime operation to move the subs across the border under the nose of American authorities.

The deal itself was a classic cloak-and-dagger affair. McBride relied on a trusted lieutenant, Lieutenant-Commander W.H. Logan, to form a sort of expert team to meet the runaway submarines in the Strait of Juan de Fuca between the two countries in the night. The plan was they would inspect the submarines on the spot and negotiate the price — filling in the final numbers and handing them a cheque from the government of British Columbia right there on the open water. Logan was skeptical at first, noting the vessels' rough state, but time was short, and McBride’s resolve was unshakable. They couldn’t afford to lose this chance.

The Night Run

In the dead of night, August 4, 1914, the two submarines slipped out of Puget Sound and navigated through the inky waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The secret navy crew that would ferry the boats back to Canada had entered the US without paperwork and wearing plain clothes. The journey was perilous. The submarines were untested, their crews inexperienced, and the threat of interception by American patrols loomed large. If caught, it would mean a diplomatic scandal of epic proportions and long prison sentences for the crews.

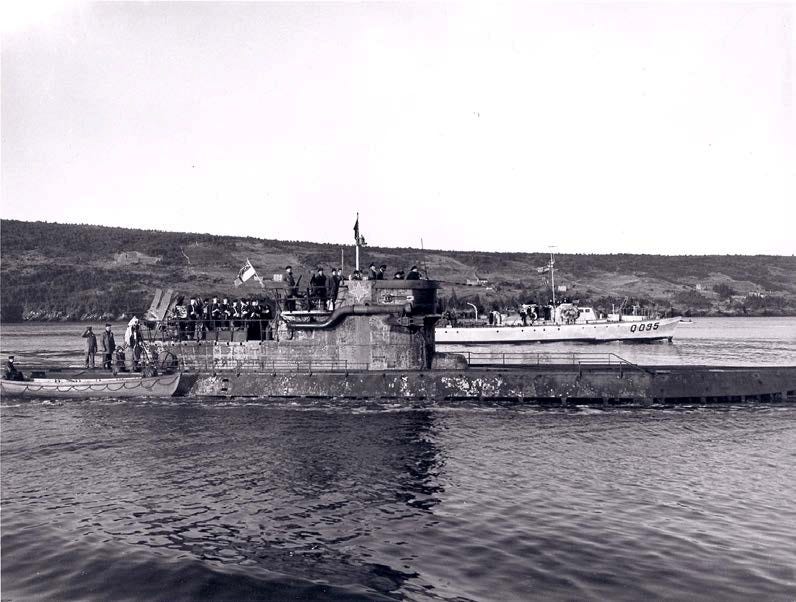

But luck—and daring—were on their side. The submarines reached Esquimalt, the pretense of a naval base near Victoria, just as war was officially declared. Canada now had its first line of Pacific defense.

The Fallout: A Gamble Pays Off

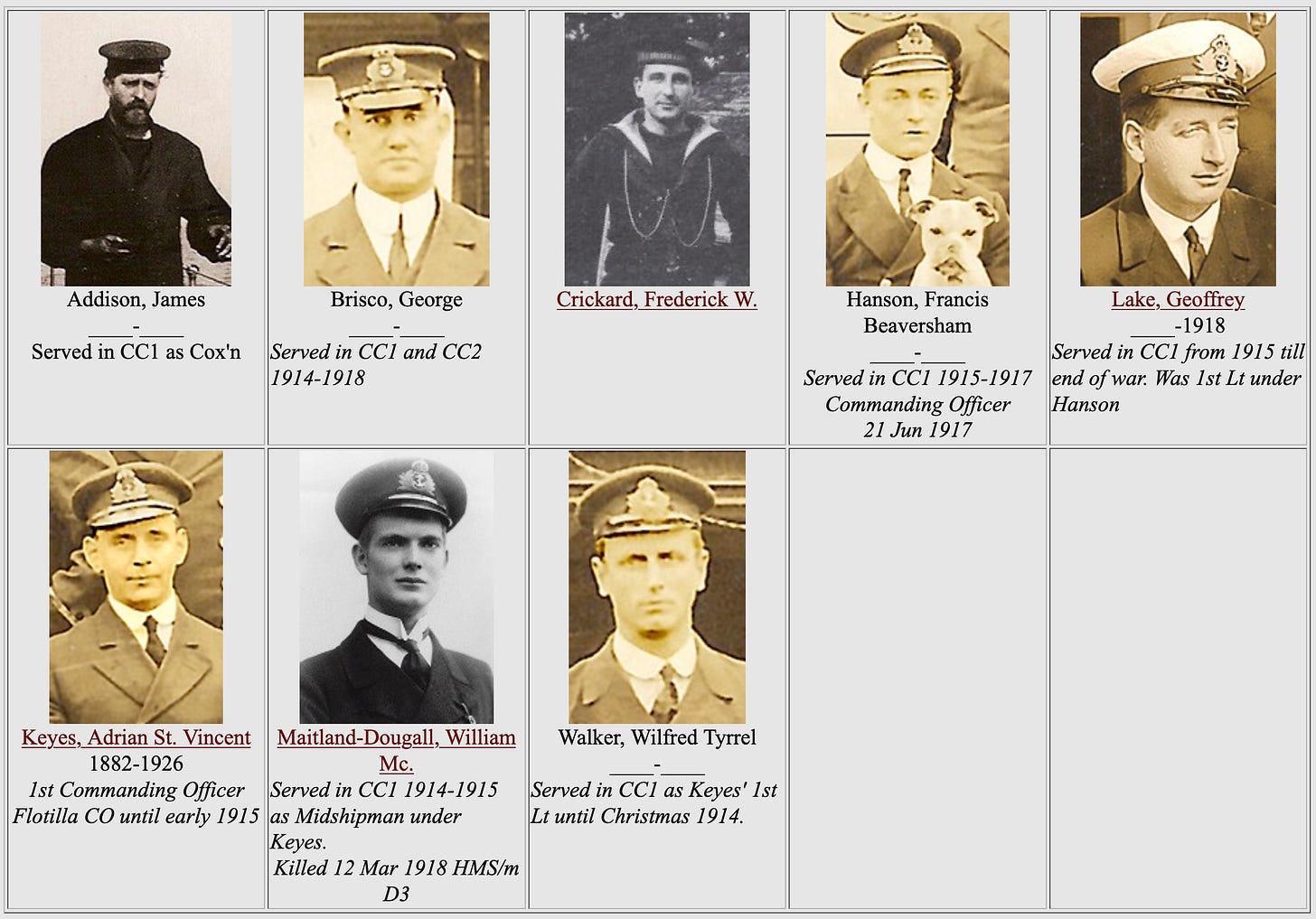

The deal’s success brought McBride both praise and criticism. Ottawa was caught off guard, initially balking at the unauthorized expense, but the urgency of the situation and the onset of war forced their hand. The federal government quickly reimbursed British Columbia for the purchase lest McBride’s navy be seen as competition with Canada, and the submarines were officially commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy as HMCS CC-1 and CC-2.

For McBride, this was a personal triumph. He had single-handedly filled a critical gap in Canada’s defenses, cementing his legacy as a wartime leader. His boldness earned him admiration, but it also underscored his reputation as a man who played by his own rules when the stakes demanded it.

The Propaganda Battle

McBribe knew how to tell and sell a story. In the media and in the global world of diplomats and warmongers the two submarines were a hyper new technology, far beyond the German’s U-Boats, able to sink German battle cruisers with almost unlimited torpedos from a distance of miles. Whatever the German fleet might have seen on the coast of BC, it seemed there was a sea of easier targets in the Pacific in warmer and calmer waters.

In truth the subs were Engineering Marvels of Their Time but unlikely to fend off a fleet of war proven battle cruisers.

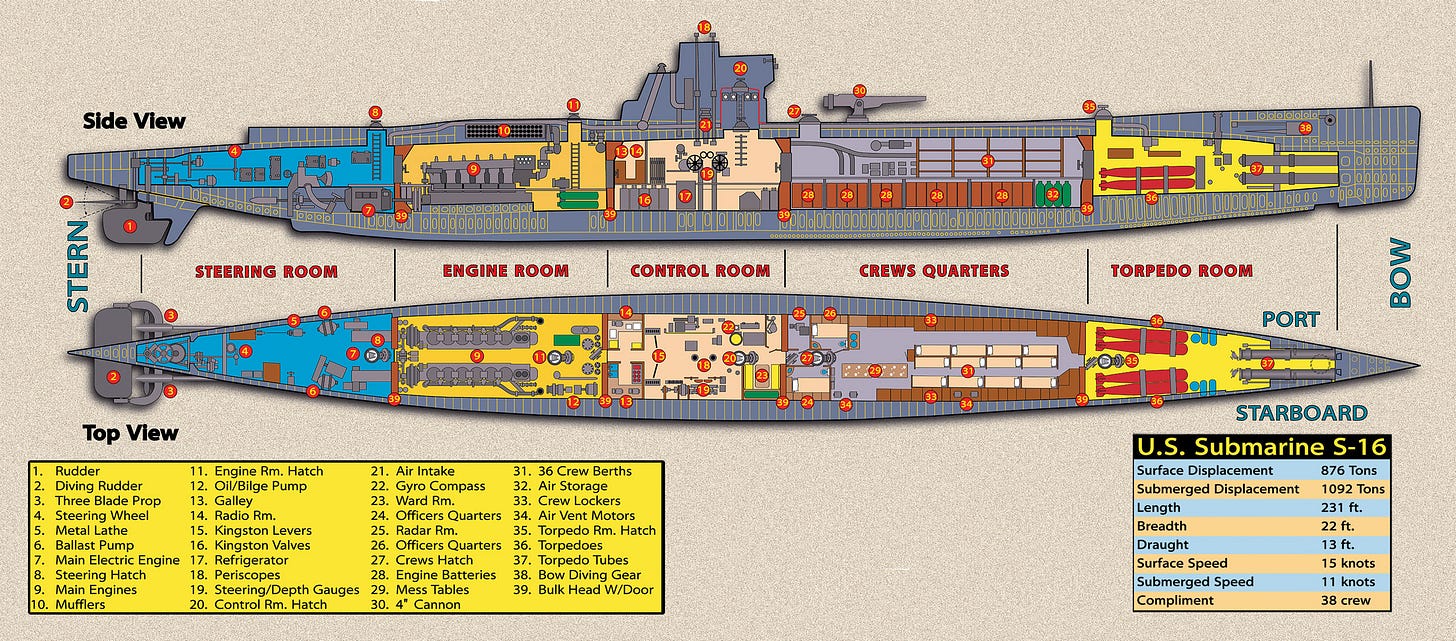

The submarines were christened HMCS CC-1 and CC-2, were products of the Electric Boat Company, constructed at the Seattle Construction and Drydock Company for the Chilean Navy. CC-1, built to design 19E, featured a bluff bow and was armed with five 18-inch torpedo tubes—four forward and one aft. CC-2, adhering to design 19B, boasted a tapered bow with three torpedo tubes—two forward and one aft. Both vessels were powered by six-cylinder MAN diesel engines to charge batteries, granting them a surface speed of 13 knots and a submerged speed of 10 knots. They could dive to depths of 200 feet and carried Whitehead Mk IV torpedoes, capable of striking targets up to 1,000 yards away at 25 knots.

The Legacy

McBride was knighted, as many who gambled and won were in wars past. But his methods made him many enemies. None worse though than his health. He died before he reached 50 having lived more than most in a dozen lifetimes.

The acquisition of CC-1 and CC-2 marked Canada’s entry into ubmarine warfare and solidified McBride’s place in history as a wartime hero. The drama of the secret deal, the high-seas smuggling operation, and the political fallout provide all the ingredients for a big mess that largely got buried in the fog of war.

This story isn’t just about submarines; it’s about leadership under pressure, the fine line between diplomacy and espionage, and the kind of bold action that changes the course of history.

As the war raged to a climax the story of Canada’s two subs had just begun. Their crazy crews — all submariners are a certain kind of crazy — now keen to get into the ‘real war’ undertook a sort of odyssey to get to the front.

The Voyage of the Iron Whales

In the solstice dawn of June 1917, Esquimalt’s naval yard buzzed with the urgency of war. British Columbia’s submarines basically the entire West Coast navy, HMCS CC-1 and CC-2, sat in the harbor, their hulls gleaming with condensation. These steel leviathans, prohibition purchased in a clandestine midnight deal, had fulfilled their initial purpose of defending the Pacific coast. But now, their mission had changed. Orders had come down from Ottawa: the submarines were to sail for Halifax and join the Royal Canadian Navy’s fleet in the Atlantic, where the real war was raging.

After three years' cruising on the west coast they were ordered to Europe, and on 21 Jun 1917, set out for Halifax with their mother ship Shearwater. On 03 Jul 1917 they arrived in Seattle and were invited to lead the Seattle Independence day Parade on 04 Jul 1917. They were the first warships ever to transit the Panama Canal under the White Ensign.

The plan was as ambitious as it was reckless. These submarines were coastal vessels, built for short patrols in calm waters—not for traversing thousands of miles of the world’s most treacherous oceans. Their diesel engines were temperamental, their cramped interiors barely fit for the skeleton crew aboard. Yet, hubris and wartime desperation fueled the decision. The characters who would command this 8,000 mile odyssey, a mix of seasoned officers and daring adventurers, believed they could beat the odds and deliver their cargo to Halifax.

The Characters: Guardians of a Fateful Voyage

Leading the expedition was Lieutenant-Commander Bertram Jones, a veteran of the Royal Navy and a man known for his unflinching resolve. His belief in the mission bordered on obsession. “A sub is only as strong as the man who commands her,” he told his crew, knowing full well the perils they faced. His second-in-command, Lieutenant Edgar Torrance, was a brooding figure with a knack for fixing the finicky diesel engines. Torrance carried the weight of every malfunction on his shoulders, a mechanical sorcerer whose tools seemed like talismans.

The crew was rounded out by a mix of misfits: Able Seaman Douglas Harkins, a former fisherman with an uncanny sense for the sea, and Chief Petty Officer Angus MacLeod, a grizzled Scot whose humor masked a deep fear of what lay ahead. Each man brought his own demons aboard, and each would confront them on the perilous journey.

The Departure: A Reluctant Farewell

This insane submarine adventure always reminds me of a famous scene from The Aeneid by Virgil. In Book 1, after Aeneas and his crew are shipwrecked on the coast of Carthage, Aeneas delivers a supposedly encouraging speech to his weary men. He acknowledges their suffering so far but urges them to remain hopeful. The key line is often translated as:

"Perhaps one day it will be pleasant to remember even these things."

(Forsan et haec olim meminisse juvabit.)

Aeneas, like a true leader, masks his own despair to lift the spirits of his crew. They've endured immense hardship—fleeing the destruction of Troy, battling storms sent by vengeful gods, and now, finding themselves stranded in unfamiliar territory. This line captures the Roman ideal of stoic endurance, suggesting that even the darkest trials can become a source of strength and reflection in the future.

But there’s a double meaning. It could be the case that however bad things have been so far they will someday seem like the ‘good old days’ compared to what is to come.

It’s a poignant moment, blending hope with the bittersweet recognition of suffering—a theme that resonates throughout The Aeneid and maybe all journeys into battle.

As the subs slipped their moorings and set out into the Pacific, a sense of foreboding hung heavy in the air. The route would take them south along the coast, through the Panama Canal, and up into the Atlantic—a journey of over 8,000 nautical miles. The first days were deceptively smooth, the seas calm and the engines humming. But soon, the reality of their task became clear.

The subs were not built for comfort or endurance. Inside, the air grew thick with the acrid stench of diesel fuel and unwashed bodies. There’s something about the smell of diesel. It’s not like gasoline, which is intoxicating and brings on a kind of euphoria. Diesel goes to your head, but not in a good way. It’s sickening. Where gasoline can stimulate dopamine and even delight the senses, diesel’s heavy, lingering aroma overwhelms and repels, causing a heavy, cloying sensation that can lead to nausea or headaches. Torrance worked tirelessly to keep the engines alive, while Harkins scanned the horizon, ever watchful for signs of enemy ships or the lurking threat of mechanical failure.

The Trial: Facing Neptune’s Wrath

By the time they reached the open waters off Central America, the ocean turned hostile. Currents of warmer less dense water battered the subs, forcing them to surface frequently to recharge their batteries and ventilate the stifling hot and stinking compartments. The tropical heat was merciless, and storms threatened to tear them apart. At one point, CC-1’s engines failed entirely, leaving the submarine adrift for hours. Torrance, drenched in sweat and cursing under his breath, worked through the night to restore power.

Their harrowing passage through the Panama Canal offered little rest. The sight of dense jungle and narrow locks brought a surreal calm, but the crews knew their most dangerous waters lay ahead.

The Atlantic: Death by a Thousand Cuts

Once in the Atlantic, the submarines faced their greatest test. The North Atlantic in Autumn Gales was a brutal expanse, its waves towering like mountains and its winds howling with icy ferocity. The subs were tossed like corks on the open sea, their steel frames groaning under the strain. Supplies ran low, and the crew’s morale frayed. MacLeod, ever the joker, began telling ghost stories of ships lost at sea, only to stop mid-sentence, sensing the despair creeping into his crewmates' eyes.

Jones, too, felt the weight of command pressing down. He knew that the odds of reaching Halifax were slim. The subs were leaking, their engines laboring, and their men exhausted. Yet, he pressed on, driven by the belief that their journey was a symbol of Canada’s resolve.

The Arrival: Broken but Unbowed

Against all odds, both submarines limped into Halifax harbor three months later. They were battered, their paint scoured by salt, their crews gaunt and hollow-eyed. But they had survived. The journey had taken its toll—engines beyond repair, morale at its nadir—but they had defied demons in the sea, in the subs, and in themselves and delivered the subs — Canada’s west coast navy — to the Eastern Atlantic Fleet.

For the men, the voyage was an odyssey of endurance and survival, a testament to human will and the limits of wartime necessity. For Jones and his crew, it was a chapter that would live in quiet infamy, a saga of hubris, desperation, and triumph on the high seas. What’s worth telling in this story — a secret struggle far from the front— only remembered by forgotten heroes of a forgotten war.

Epilogue: A Mission Misguided?

Laid up in Halifax Harbour both ships had arrived just in time for the Halifax Explosion. They survived the blast that happened little more than 500 metres away. But it further rattled their iron bones.

In retrospect, the mission was seen by many as a folly. The submarines, unfit for Atlantic warfare, saw little action beyond Halifax's coastal defence before being decommissioned. They couldn’t cross the Atlantic in their condition, maybe they never could have. Yet, their journey from Esquimalt to Halifax remains a dramatic footnote in Canada’s wartime history, a story of bravery and stubborn resolve in the face of overwhelming odds. Like the story of Aeneas, a Trojan prince in the Aeneid and a minor character in The Iliad, it was a reminder that sometimes, the greatest battles are fought not with enemies, but with the sea itself.

The Battle of Musquodoboit Harbour

On this day in 1945 U-Boat Commander, Hans-Erwin Reith snorkeled his 250-foot-long submarine in shallow water along the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia. He had been Commander for just six months and had turned 25 years old just before setting sail for Nova Scotia.