The Battle of Musquodoboit Harbour

The Last U-Boat in Nova Scotia and the Last Canadian Ship Sunk in War

In the early spring of 1945 U-Boat Commander, Hans-Erwin Reith snorkeled his 250-foot-long submarine in shallow water along the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia. He had been Commander for just six months and had turned 25 years old just before setting sail for Nova Scotia.

By the end of March 1945 most people, especially in the military, had a sense that the war was coming to an end. Canadian forces were in Germany, the first concrete talks of surrender were held with German forces, and the Allied invasion of Germany officially began. We can only imagine how all this made people feel after five dark years of war.

I learned what happened next off Musquodoboit Harbour from Scott Macmillan’s telling of his father’s story. Scott is a well-known local musician. He has even written a Symphony called Within Sight Of Shore about what ended tragically, and many believe needlessly, as the last Canadian naval battle of World War Two, and the last Canadian ship to have ever been sunk in battle.

It happened right off our shore, famously, within sight of land. Sometimes our little rural region can feel far from the action. But in truth, we’re connected to the frontline of change. The way things go around the harbour can be a harbinger for the whole of the world.

HMCS Esquimalt was under the command of Scott’s father, Lieutenant Commander Robert Cunningham Macmillan, RCNVR. On the evening of April 15 in Halifax, MacMillan shared drinks with the Commanding Officer of HMCS Sarnia, Lieutenant Bob Douty. In the early morning of April 16, 1945 the two sister ships went out to patrol for German U-boats that were rumored to be in the area.

Sarnia headed west and Esquimalt headed east from the mouth of Halifax Harbour towards Musquodoboit Harbour, agreeing to rendezvous back at the mouth of the harbour at Buoy “C”.

The sea was calm with a long, low swell and visibility was good in the morning twilight. There was no need for radar. The Eastern Shoreline was clearly visible. Macmillan and his crew knew the area well. Maybe too well, and maybe their guard was down a little. The rumours of U-boats within sight of the Eastern Shore had been going around for years, but they’d never seen one in so close.

But times had changed. The days of the U Boat Wolf Packs prowling the surface of the mid-Atlantic were long over. Now U-boats operated alone with snorkel systems that allowed them to run their engines while submerged.

At 25 years old, U Boat Commander Reith had only learned one trick we know of. Stay in shallow water along the quiet shore where U-boats aren’t expected.

Near Musquodoboit Harbour at the end of Esquimalt’s morning run, U-190 heard the pinging sound of the minesweeper's sonar. Below the surface, the Germans listened intently as Esquimalt circled above at 10 knots, and according to Reith’s testimony, "passed overhead two or three times".

When no attack followed, Reith took U-190 up to periscope depth for a quick look around. He observed the little warship through the periscope at a range of between 1,000 and 2,000 metres. It suddenly turned towards him and closed rapidly.

This wasn’t how it was supposed to go. Esquimalt was just passing the time. The U-boats had limited torpedoes and they were meant for big fat freighters, not little Canadian coastal patrol ships. Fearing they were caught, Reith, believing he had no choice, fired an acoustic homing torpedo from a stern tube as he retreated. The torpedo hit Esquimalt at 6:30 AM, ripping a gaping hole in the starboard quarter right where its depth charge munitions were stored. The explosion knocked out the power instantly, preventing the radio room from sending a distress signal. Esquimalt listed heavily to starboard, beginning to sink immediately, and the emergency lighting failed. No power for a distress call and no time for flares in the chaos.

MacMillan raced from below after surveying the damage and made his way to the bridge where he gave the order to abandon ship. The heavy list to starboard pushed the single life boat under water before the crew could release it from the davits. They succeeded in getting four Carley floats – imagine a 12 foot oval dingy shaped metal tube with canvas mesh in the centre and rope all around - clear of the ship and plunged into the icy water after them.

Everything was a mess. Fire on a ship is a terrible thing and the cold sea pouring in was worse. Some men were trapped in the wreckage of the ship.

The ship sank in five minutes.

It was only three weeks before VE-Day, the official end of the war.

The survivors huddled together, nearly swamping the rafts. An aircraft flew overhead just ten minutes later and sighted the Carley floats but thought they were fishing boats out of the Harbour and made no report.

The sun rose higher in the sky, shining brightly. At least it was calm but it was as cold as you would imagine on a day like this. At first the men sang to keep their spirits up, later MacMillan led them in prayer. Gradually, one by one, they succumbed to the cold and let go of the raft, only to drift off a little - floating in the calm sea.

Two minesweepers, on their daily sweep, closed to within two miles at 9:30 AM but moved on without seeing the survivors or hearing their desperate calls for help.

The young U-Boat Commander, Reith had watched his victim sink through the periscope and then put some distance between him and the position of the sinking. He moved into even shallower water toward Musquodoboit Harbour, reasoning that Canadian forces would expect him to move out to deeper water to escape.

Chezzetcook, Petpeswick, Musquodoboit. We don’t know exactly where the U-boat rested on bottom. They didn’t go as far as the lights at Jedore or Egg Island. They would have looked for a shallow sandy spot where there were lots of big rocks around so the boat could blend in. Shallow enough to stay submerged on bottom but get air through its new snorkel system.

Aboard the rafts, the numbers dwindled more as the hours passed. One Carley float had started out with thirteen men but they died from exposure one by one until only six were left.

An aircraft, sent out to search, sighted the rafts and flashed their location to Sarnia by signal lamp. MacMillian’s friend, Douty got Sarnia to the survivors at 12:30 PM, six hours after Esquimalt had been torpedoed. Sarnia rescued twenty-one men (not including six who reached the Eastern light ship) and recovered the bodies of sixteen others floating on the calm silver sea. The survivors were revived with rum aboard Sarnia and taken to the RCN hospital in Halifax. In total, twenty-seven men survived and forty-four died.

At Halifax Admiral L.W. Murray, RCN, Commander-in-Chief, Canadian Northwest Atlantic, organized a hunt for the U-boat. The ships found no trace of the enemy sub.

U-190 lay on the bottom near shore, only a few metres below the surface. The United States Navy's Task Group 22.10 hunted farther down the shore while more RCN ships joined in on 19 April but they were in deep water, no one found any trace of U-190. Murray called off the unsuccessful search on 21 April.

Lying low, Reith remained submerged on the Eastern Shore for seven days and nights after the attack and later recalled that he could see "Canadian search groups worked excellently" but did not suspect that he had moved into such shallow water.

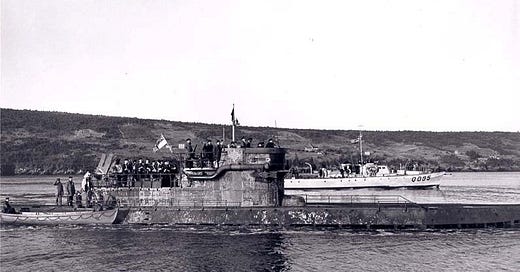

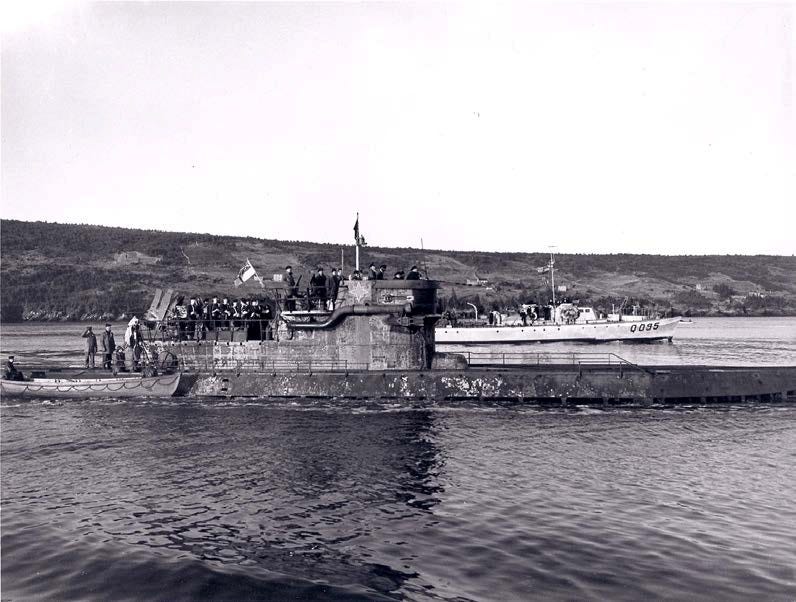

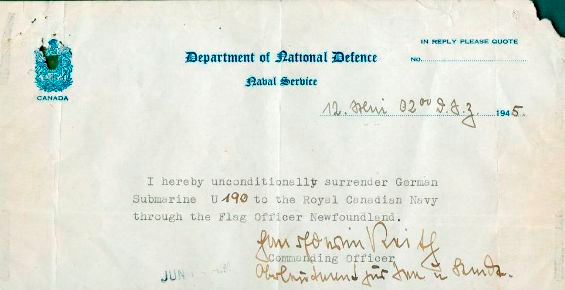

U-190 headed for home on 29 April, but never reached Germany. She received U-Boat Command's signal for all submarines to surrender on 11 May, and broadcast her position in plain language. HMCS Thorlock and HMCS Victoriaville arrived on the following day and escorted the U-boat to Bay Bulls, Newfoundland then eventually back to Halifax.

In a twist of fate U-190, a perfectly serviceable sub, was drafted into the Canadian Navy and toured for two years along the coast.

In October 1947, the Canadian Navy sank U-190 as a target during Operation Scuttled, a live-fire naval exercise off Halifax– near the site of Esquimalt‘s loss. It was to be epic, with the Tribal-class destroyers HMCS Nootka and HMCS Haida (my father’s ship in Korea) using their 4.7-inch guns and Hedgehog ASW mortars on her after an aerial task force of Seafires, Fireflies, Ansons and Swordfish worked her over with ordnance.

Poignantly, the U Boat was painted in lurid colours and taken down the Eastern Shore to the place where it had sunk the Equimault and then hid for all those days.

It only took a few minutes for the destroyers to sink the sub. These guys knew what they were doing and were keen to show off their skills. Nonetheless, for a destroyed U-boat, U-190 is remarkably well preserved as relics of her are all over North America.

U-190‘s war diary is in the collection of the U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command.

The working Enigma machine recovered on U-190 is now part of the Canadian CSE’s (Communications Security Establishment)– the country’s crypto agency collection of historical artifacts.

The Canadian War Museum has her pennant, star globe, equipment plates, a C.G. Haenel-made MP28/2 Sub-machine Gun seized from her armory (which had been on display at Naval Service Headquarters in Ottawa until 1959) and other gear.

And of course, U-190‘s sky periscope, one of just five such instruments preserved worldwide, has long been in the care of the historic Crow’s Nest Officers Club in St. John’s, Newfoundland where its top sticks out over the roof to allow members and visitors to peak out over the harbor.

Esquimalt was the only ship Reith sunk and she and her crew are remembered every year at a public ceremony far across Canada in the pretty little town on the tip of Vancouver Island, British Columbia that was her namesake.

Today the Esquimalt and the U-190 lay together on the bottom off the Eastern Shore.

Somewhere.

In my TV work, since the earliest days of the Sea Hunters with National Geographic, I’ve spent years, and more money than I care to admit searching for both of them. None of the wartime co-ordinates are right. The details of the navy search, that didn’t find the ship or the sub are of little help. In six hours the rafts had drifted far from the sinking sight with no records saved. And as Reith knew, the bottom off our shore is littered with big boulders and ridges that, even to modern side-scan sonar equipment, all look like submarines and shipwrecks.

But one of these days, probably with the help of our friends from Dominion Diving, the Bedford Institute of Oceanography, and my friend Tony Sampson, we’ll be able to say where those ships are. Maybe it will be in time for the 80th anniversary of the sinking and the end of the war.

Thanks for reading The Bee! Subscribe for free to receive new posts.