Taking The Wrong Road To Nowhere in Halifax

The idea of a hyper-dense downtown workplace, fed daily by streams of commuters flowing in and out like tides, is no longer the dream. For most people, it's the nightmare.

I took these photos on a walk through Halifax on a sunny Sunday morning.

If you think, well, he just pointed his camera in directions that made everything seem awful, I challenge you to do any different. Take a walk through the city. Take a dozen photos. Not of people, flowers, the last of the historic architecture, or nature surviving in spite of everything. Take a dozen pictures of the city itself. In fact, take as many as you like. Take pictures of the latest things. The new buildings. The sidewalk ‘improvements’. Take your time. The challenge is to find one beautiful thing. One single thing that in a generation from now people will gather or visit to say look how good this is.

The Wrong Road:

Why Widening Robie Street Is a Mistake Halifax Will Regret

Halifax is spending $64 million to buy up land and widen Robie Street for bus lanes. It’s a textbook case of outdated urban planning masquerading as progress. While the intention—to improve public transit—is commendable, the method threatens to erode the very fabric of the communities it aims to serve. It's a plan from the past— of a future that's not coming. The idea of a hyper-dense downtown workplace, fed daily by streams of commuters flowing in and out like tides, is no longer the dream. For most people, it's the nightmare.

This project doesn't build a city. It hollows one out.

EDIT: The CBC number I used above was wrong.

Its $74m is for the purchase and demolition of buildings. These have increased drastically each year- 2023- $53m; 2024-$73m had a 30% increase in property value.

The most recent HRM estimate or the final figure for buy, demolish, cut, build the wider road is $163.8million. FHC has been using the figure of $200m for a low ball number for the constructed cost.

Final road cost and construction could be more than $200mby 2029/2030

Each road widened is a place lost. A place that was—or could have been—a neighbourhood. A place where someone might have opened a bakery, where kids might have walked to school, where a porch light might have shone as a symbol of safety and presence. Instead, we get a wider road: loud, fast, lifeless. We get a liminal space, the kind of place people pass through but never stay. Nothing nice lives there. Nothing memorable, nothing cherished.

And all for what? To serve a model of growth that assumes more is always better, that density is destiny, and that if we just keep expanding, eventually we’ll arrive at some ideal form. But cities are not cancers. The economics doesn’t work. After a point, growth will cost more than it delivers. More is lost than is gained. Nothing is meant to grow without bound. There is a right size for a community—one that reflects its geography, its values, its culture. That size should be planned and aimed for, not stumbled into through bureaucratic inertia and 1970s traffic models.

What’s the Better Way?

Let’s propose a pivot—a plan rooted not in asphalt but in aspiration. Halifax should aim for living streets: roads that are narrow, slow, and shared. Streets that make space for people, not just vehicles. Cities across Europe, and increasingly North America, are turning urban roads into neighborhood assets—green, calm, walkable corridors where children play, cafes spill onto the sidewalk, and mobility includes feet and bicycles and community buses.

But vision is not enough. We need to do the math.

Set real, evidence-based density targets. Determine what level of population, infrastructure, and services actually create the kind of livable, prosperous city we want without tipping into dysfunction. Acknowledge that density is a tool, not a goal. Growth should serve quality of life, not the other way around.

A City Made for Living

This isn’t anti-transit. It's pro-place. We want Halifax to build transit that connects neighbourhoods, not corridors that destroy them. We want homes with porches, corner stores, public gardens—not endless lanes of traffic slicing through once-livable spaces.

If Robie Street becomes a highway, we will have paid millions to erase what little urban fabric we have left in the core. We will have chosen throughput over presence, and in doing so, we will have forgotten what makes a city worth living in.

The Globe and Mail addressed all this in a Special Report this week.

The Ghost of a 1970s Dream

Halifax, like many North American cities, is still largely planning as though the world hasn't changed. We continue to invest in widening roads, adding bus corridors, and rezoning for mid-rise apartment blocks along commuter routes that were designed to funnel workers from sprawling suburbs into a downtown core of office towers. This model—suburb-to-downtown, 9-to-5, white-collar work—is not just out of date; it’s actively dead-ending us.

That vision was born in the 1950s, matured in the 1970s, and should’ve been buried by the 2020s.

What We're Still Building For

We are still zoning, planning, and investing in infrastructure for a world where:

People own single-family homes far from the core.

Jobs are concentrated downtown, mostly in government, finance, and corporate offices.

Commuting is a daily inevitability, and success means reducing travel time to the core.

Public transit is a bus that brings you to a desk job.

But this isn’t how most people live—or want to live—anymore. Work has decentralized. Offices are shrinking. Hybrid and remote work are sticky. And younger people increasingly prioritize walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods over commutes and cul-de-sacs.

And still, city hall clings to the image of a bustling, dense downtown of office workers as the economic engine of the city. Why?

Why We Keep Doing It

There are three primary reasons:

Institutional Inertia

Planners and policymakers were trained in the logic of the 20th-century city. The tools, the modeling software, the funding mechanisms—all assume the same basic structure of centralized economic activity. Change requires unlearning.Path Dependency

Decisions made decades ago created physical and political structures that are hard to undo. Halifax’s transit routes, zoning maps, and even sewer systems are built around the funnel.Fear of the Unknown

It’s easier to double down on what was than to risk a bold bet on what could be. And many of our political and institutional leaders still draw their salary from those same government desks downtown.

What We Lose

By clinging to this outdated model, we sacrifice far more than we realize:

Housing Innovation: By prioritizing high-density corridors and ignoring village-scale development, we miss the chance to create diverse, walkable communities outside the core.

Economic Resilience: A city built around one kind of job in one place becomes brittle. We neglect trades, creatives, makers, and home-based or gig work—forms of employment that don't fit the downtown funnel.

Civic Life: When every neighbourhood is a bedroom and every job is somewhere else, people lose the chance to live, work, and participate in community close to home.

Environmental Goals: Long commutes, even by transit, are still worse than walkable lives. Building for distance locks in carbon emissions.

Imagination: Most tragically, we lose the chance to imagine a new kind of city—one where neighbourhoods are self-contained and alive, where work and life are interwoven, and where success isn’t measured by the height of a skyline but by the richness of a local life.

The Opportunity

If we stopped building for the past, Halifax could lead the country in the new economy of place:

Decentralized Work Clusters: Small offices, creative studios, and co-working spaces in every district.

Neighbourhoods: Where work, school, groceries, and green space are within decent distance.

Village Density: Instead of pouring concrete towers into urban corridors, allow infill and multi-unit homes around shared spaces.

It begins with a change of goal. Stop trying to funnel workers. Start trying to foster life.

The City We’re Still Building—And Why It’s Already Dead

Halifax keeps building for a future no one believes in.

Every new rezoning, every widened road, every bus corridor and density corridor quietly serves the same outdated vision: a commuter funnel, shuttling workers from suburbs into a downtown office core each day—where they sit at desks in government departments, banks, and the regional branches of national corporations.

But here's the thing: that world is over. The office isn’t coming back—not like it was. And even if it were, no one should want it.

White Collar Dreams, Blue Collar Neglect

Part of what keeps this dead dream alive is our deep, unexamined worship of white-collar work.

From the earliest days of school, our education system sorts kids into two paths: one that leads to university and then to an office, and another that leads to trades, service, or care work. The message is clear, if unspoken: the bright kids go on to write emails for a living. The rest take what’s left.

This is not only wrong—it’s economically suicidal.

We’ve designed an entire city, and a whole generation of young people, around a brittle definition of success: an apartment near downtown, a government job, a laptop and a lanyard. But white-collar work is not the backbone of a thriving city. It’s not even close.

Cities work because people do things. They build, fix, care, deliver, cook, clean, wire, weld, and create. They grow food, make art, run businesses, raise children, take risks. And these people are being written out of the urban vision.

What We Lose

When we plan our city around funneling “knowledge workers” into an increasingly irrelevant downtown, we lose:

Respect for Real Work: The kind that gets your hands dirty and your muscles sore. It’s not second-class; it’s foundational.

Economic Flexibility: By overinvesting in white-collar infrastructure, we underinvest in the trades, local entrepreneurship, and hybrid work models that could power our future.

Social Cohesion: When the education system treats trades as a fallback and treats those who take them as failures, we bake in a class divide that erodes trust and mutual respect.

Future Builders: We are staring down a massive shortage of tradespeople, technicians, and skilled doers—and we’ve spent decades actively discouraging kids from becoming them.

A Better City Is Possible

It starts with breaking the spell of the office.

Not everyone needs to work downtown. Not every great job requires a degree. And not every good neighbourhood needs to be a dormitory for office workers.

We could build a Halifax that respects all kinds of work, that redistributes opportunity, and that encourages local economies in every community—from Spryfield to Sheet Harbour.

Let’s stop funneling people toward a future we don’t believe in.

Let’s build a city that believes in itself.

Let’s not design our city around a future no one wants. Let’s build for the one we do.

Road widening does one thing very well: it creates more space for cars. But what does this accomplish in a city striving for better health care, lower taxes, more housing, a fairer economy, and a healthier environment? Does it serve these goals, or does it stand in opposition to them? And since Halifax is mostly rural does it make sense to rob rural tax dollars for more and more "urban and up" ideas like this.

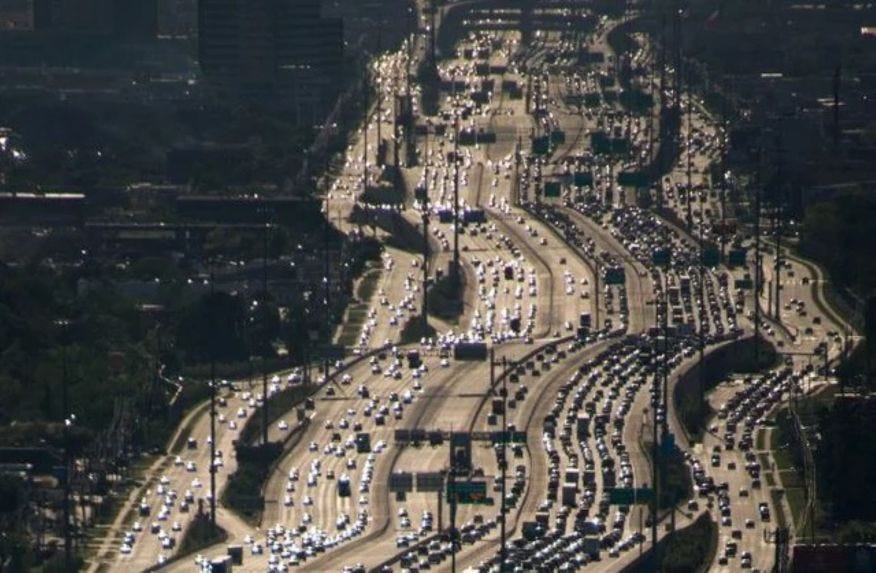

Widening Robie Street would, effectively, create another downtown highway. The kind that many of the world's most interesting downtowns from New York to Toronto are trying to remove as they now seem like costly mistakes. Highways are efficient for moving vehicles, but they also cut through communities - dividing, diminishing, destroying, and ultimately costing everyone more in the long run.

We have to stop and ask ourselves: what kind of city are we trying to build? A "more asphalt" solution runs counter to the vision of Halifax as a vibrant, human-centered city.

What are we really trying to achieve, and how does this specific solution align with our civic priorities? Without a clear statement of intention, we risk defaulting to outdated ideas that solve yesterday’s problems while creating new ones for tomorrow.

Before we start cutting trees, demolishing apartments, and laying asphalt we need to stop and create a shared statement of purpose. Something like this:

"Our goal is to create a city that balances the movement of people and goods with the broader needs of a living community with affordable housing, environmental sustainability, economic fairness, a high quality of life, and places for people to gather and enjoy. We need solutions that align with these values, ensuring Halifax remains a nice, prosperous, and resilient place for generations to come."

The Hydrostone, Halifax. High-density, high-efficiency, urban housing for over 1,200 people with all walkable amenities, green spaces, and services built in less than two years, is now more valuable than ever to families, to the city, and to the future, over 100 years after it was built.

We all know what a nice home, a nice street, a nice neighbourhood looks and feels like. No one is confused. We know simple homes built with sustainable local materials, and workers of average skills, can be built quickly, inexpensively, and safely and built to last over 100 years while increasing in value (and taxes paid) consistently without any great drain on the city's infrastructure. We can literally see it incarnate in the city.

We also know that, once built, they can be upgraded as needed and as affordable to embrace changing styles, uses, and technology. We know that neighbourhoods and towns built this way in similar climates in European centres have stood for hundreds of years and just get more beautiful and valuable with time.

The only question is why aren't we building like this? Why aren't we creating the kinds of places the luckist among us save and scrimp to go on holidays just to stand in for a few days? Why don't we build the towns people are waiting for? Or better yet why don't we restore the dozens of towns and villages from Amherst to Canso that we've let fall into disrepair as we put all our eggs (and people, and businesses and services) into the basket of Halifax. Why are we taking a 'first little pig' approach to development and letting our city growth be a cost - a net drain on our wealth - rather than a valuable investment in the rising generation before us?

https://thebeens.substack.com/.../a-high-rise-isnt-a...

good article - should be a must read for HRM's planning department

Amen! Could you please go and talk to city Council because they're going backwards and nowhere all at the same time!