“How do you get such intimate pictures of the horses?” I asked photographer Roberto Dutesco.

“You wait,” he said.

“If you chase wild horses, you just get pictures of their ass.”

For National Canadian Film Day, I want to share an early film we made at Arcadia, and the story of how it came to be.

By Far and away, the best place in the world to see the wild horses of Sable Island is at Union Square in New York City

When I started Arcadia Entertainment in Halifax in 2000, my aim was to make factual films. What they used to call documentaries. But the landscape had already shifted. Discovery, History, National Geographic, Smithsonian, and a wave of Lifestyle channels were rising in popularity. That was where the business was. Since then, we've made over 500 shows for them.

I began the company with seven ideas. One of them was a story about the Sable Island horses — their true origin, their history, and their uncertain future. I tried to pitch it every way I could think of: as a nature show, a history piece, an environmental documentary, even an adventure tale. None of it landed. The new networks wanted series, high stakes, and grizzled men yelling into the wind. CBC turned it down a dozen times for a dozen reasons. I was left with just the world market — everyone but Canada.

Then, in the fall of 2006, a friend from Discovery called to congratulate me on the film’s New York City debut. I had no idea what she was talking about. She said she’d seen the horses and the island, the very images I’d been pitching for years, splashed across the giant screens on the Sony building on Madison Avenue. Majestic, cinematic, and completely unexpected.

It took a few days, but I tracked it down. Roberto Dutesco, a well-known New York fashion photographer — think supermodels, Vogue covers, Victoria’s Secret — had somehow heard about Sable. He made the journey himself, photographed the horses as if they were runway icons, which in his eye, they were. He opened a gallery on Crosby Street in SoHo to showcase his massive glass-and-silver prints of the animals. It was a huge success. New Yorkers love their city, but they also love an escape, and in spite of the geography, Sable is about as far from NYC as it is possible for a human to imagine.

I went to meet him. We hit it off right away, drawn together by this shared fascination. And that’s when I finally saw the story clearly: it wasn’t about ecology, or history, or even the horses. It was about beauty. It had been all along.

After seven years of rejection, I stood at a distributor’s booth at the market in Cannes in the spring of 2007 and proposed a new angle — a story about beauty, and the artist who found it. They said yes.

Back in Canada, now pitching it as an arts doc, the project was quickly picked up by Bravo. CBC's Halifax office — after years of Toronto saying no — came in for a small second-window license.

Sidebar: Don’t Defund the CBC — Decentralize It

Calls to defund the CBC are loud these days — and it’s easy to see why. 250 Front Street is an abomination. Contrary to Canada. A Toronto-based ideologically driven bureaucratic empire with a billion-dollar budget that often feels more like a public relations firm for Ottawa ideology than a national broadcaster. But the answer isn’t to pull the plug. It’s to change the channel, back to one that reflects the country.

What if we decentralized the CBC!

That’s how it used to be. Before the age of clickbait and national branding exercises, CBC was a loose network of regional voices — from Cape Breton fiddlers to Prairie poets, the North’s true spirit to Newfoundland’s satire. It was messy, diverse, and alive. It sounded like Canada.

Today, that spirit survives mostly in old tape reels and memory. But it doesn’t have to stay that way. The BBC, for all its faults, remains regionally structured, with strong production centers in Manchester, Glasgow, Belfast, and Cardiff — not just London. Each region produces content that reflects, elevates, and challenges its own region — authentically local with universal themes.

Decentralizing CBC would mean re-funding regional hubs directly. Halifax, Yellowknife, Windsor, and Saskatoon would get real budgets, real authority, and the freedom to tell their own stories in their own voice. Ottawa would set broad mandates — public interest, regional balance, Canadian content — but not micro-manage the programming like it was branding an ideological yogurt.

It wouldn’t just be good policy. It would be good TV… or content, I guess we’d say these days. And more importantly, it would be good for democracy.

Because when people see themselves and the things they care about reflected on screen — not as caricatures, but as complex, regional, flawed, funny, and real — they’re more likely to tune in. And maybe even believe in this country again.

With everything in place, the financing closed. And in 2008, we delivered the film. It went on to win a bunch of international awards, CHASING WILD HORSES has been aired hundreds of times in Canada on many channels, and has been one of our top ten global sellers ever since.

Much has changed on Sable since then. It’s now a National Park. That might sound like a victory — and it is in some ways — but controversially, it has also led to a sharp increase in traffic to and around the island. We’ve drifted back to where we were 60 years ago, when John Diefenbaker, hearing the public’s concern, proposed that maybe Sable — and the wild animals who lived there — could be one thing we just leave alone. In 1960, faced with the government's plan to remove and potentially slaughter the horses, Diefenbaker responded to public outcry, including letters from schoolchildren, and enacted legislation protecting the herd under the Canadian Shipping Act.

I don’t think any of that is right.

After meeting Roberto, I began to see Sable as a case study — a vision for how artists might play a role in an ecologically sound approach to environmental preservation and increase. A hundred thousand people could visit the island with their iPhones or drone cameras — and many have — but none would capture even a fraction of the vision Roberto shared with millions, including the citizens of New York City, about as far from Sable as one can get.

In this way, artists can be our eyes and ears in the places too fragile to tread. They can show us what we came to celebrate, without having to ruin it in the process.

For me, through all these years, I’ve made it a point to never go to Sable Island. And I promise I never will. I’ve felt more connection to and understanding of the island and its horses through Roberto’s images than I ever could have by tramping around on the beaches there and bothering the animals.

Art and artists help mediate our relationship with beauty by translating the overwhelming, often indescribable qualities of the world into forms we can hold, revisit, and understand. Beauty, in its raw state, can be too vast or too fleeting — a crashing wave, a wild horse, a starry night. Artists slow it down. They frame it, interpret it, and offer it back to us not as spectacle, but as invitation. They make beauty legible. In doing so, they also help us discern the difference between surface prettiness and deeper aesthetic truth — between what merely pleases the eye and what stirs the soul. This mediation isn’t just decorative; it’s moral. It reminds us that beauty is not a luxury or a distraction, but a way of knowing — a means of understanding what matters, and why.

RELATED:

The Battle of Musquodoboit Harbour

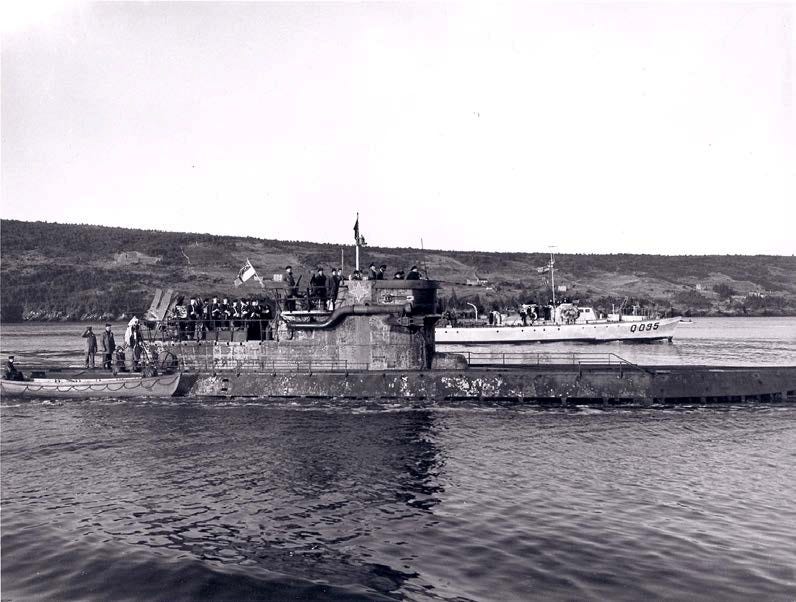

In the early spring of 1945 U-Boat Commander, Hans-Erwin Reith snorkeled his 250-foot-long submarine in shallow water along the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia. He had been Commander for just six months and had turned 25 years old just before setting sail for Nova Scotia.

Share this post