Born in The USA... But Left Behind By Globalization

Before we fight tariffs in a trade war, are we sure we’re on the right side?

How did Bruce Springsteen see the collapse of American industry coming while economists were still preaching free trade utopia?

It’s not a mystery. He was looking where they weren’t—at the local impact, beyond the allure of efficiency and cheap TVs.

This matters because it proves a simple but powerful truth: your lived experience and firsthand observations are just as valid as the theories spun by LSE- or NYU-trained economists.

The situation. The New York Times reports tariffs, set to take effect Tuesday, amount to a declaration of economic war against America’s three largest trading partners, which have threatened to retaliate in a tit-for-tat that could escalate beyond any such conflict in generations. Mr. Trump’s decision to follow through on his tariff threat raises the stakes in his hard-edged America First approach to the rest of the world, with potentially profound consequences.

Springsteen Called It

First off, as these tariff wars begin, let’s admit we owe Bruce Springsteen a long-overdue “you were right.” Decades before politicians and economists started grappling with the downsides of globalization, Springsteen was already telling us—loud and clear—how working people were feeling about it. While Donald Trump was still dancing at Studio 54, The Boss was painting portraits of shuttered factories, broken promises, and towns left behind by the relentless march of free trade and automation. Songs like My Hometown and Youngstown weren’t just nostalgia or blue-collar romanticism—they were warnings.

Bruce saw it coming long before the economists did.

Springsteen gave voice to the workers who watched their livelihoods shipped overseas and sensed, even then, that the American Dream was becoming a rigged game. It took decades of economic dislocation, a financial crisis, and the rise of populist fury for the world to catch up to what he had been saying all along: that trade deals and corporate globalization weren’t just numbers on a spreadsheet; they were seismic shifts that rewrote the social fabric, leaving millions struggling in their wake. Maybe if more people had listened to Springsteen instead of dismissing him as just another troubadour of the past, we wouldn’t have been so blindsided by the political and economic upheavals of the present.

Recorded in 1983… Precient.

Is protectionism really the dirty deal Globalists say it is?

Or were we lured off the road to real prosperity by cheaper TVs and cars?

Before Canada reflexively resists tariffs and plunges into a full-blown trade war, we should ask ourselves: Are we certain that, all the bluster aside, Trump’s core premise—that tariffs are good and that globalization has gone too far—is entirely wrong? The prevailing assumption that more trade is always better has been treated as an economic shibboleth, but what evidence do we have that the current level of global integration is optimal? Over the last several decades, free trade has undeniably driven economic growth, lowered consumer prices, and expanded markets, but it was not the only possible road to prosperity and it has also hurt households, hollowed out domestic industries, increased economic dependence on geopolitical rivals, exacerbated regional inequality, and fundamentally changed the nature of work.

It’s not just Canada, the US, and Mexico. China, maybe the greatest ‘winner’ in the trade war of globalization, could also be the biggest loser as it effectively pays for the world’s consumption binge and calls it economic progress. China’s trade surplus — the amount by which its exports exceeded imports — reached almost $1 trillion last year. Exports, and the construction of new factories to make further exports, are practically the only area of strength these days in the Chinese economy. China’s exports to the entire world rose more than 12 percent last year by volume, but the increase in dollar terms was only half as much, as companies slashed prices. Most importantly households, once the measure of increase, are suffering and there is a fundamental population crisis… because babies, babies, babies, the basic building block of the future are not being born.

The pandemic exposed the fragility of global supply chains, forcing many countries, including Canada, to reconsider their reliance on foreign manufacturing for essential goods. Meanwhile, China’s strategic use of trade policy as a tool of economic coercion if not full-on warfare has demonstrated the risks of being overly dependent on a global system where not all players operate under fair or reciprocal rules. We have to recognize that the notion of China as the workshop for the world destroyed more factories, displaced more workers, and disillusioned more young people than all the bombs and propaganda of two world wars ever did. For those ecologically and socially inclined - most can see that shipping our polluting industry and our worst jobs to Asia may be out-of-sight-out-of-mind, but it didn’t change anything and may be materially worse than Western oversight. Rather than blindly defending the status quo, Canada should take this moment to critically assess whether the existing trade paradigm serves our long-term national interests—or if some degree of economic protectionism might, in fact, be a necessary correction.

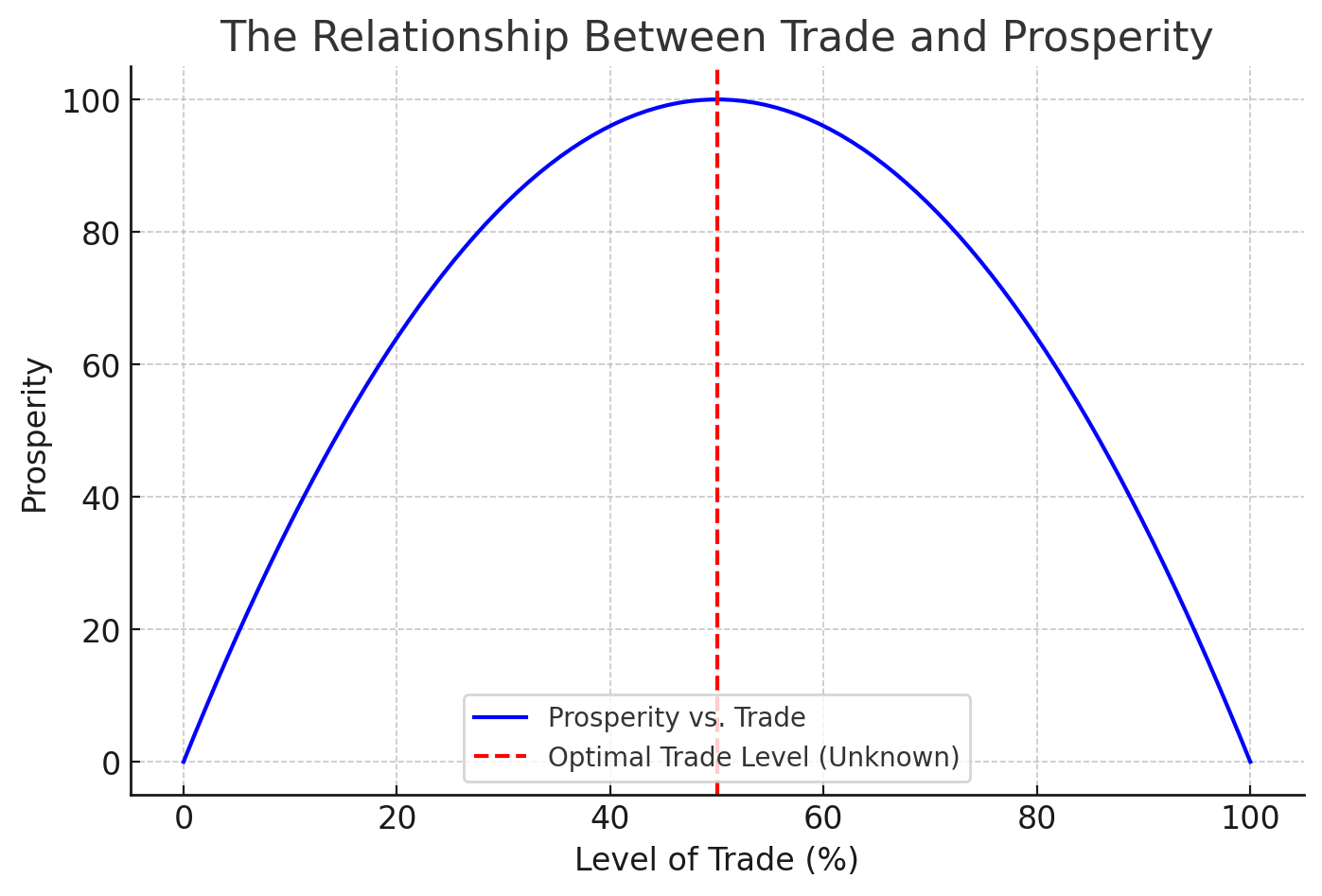

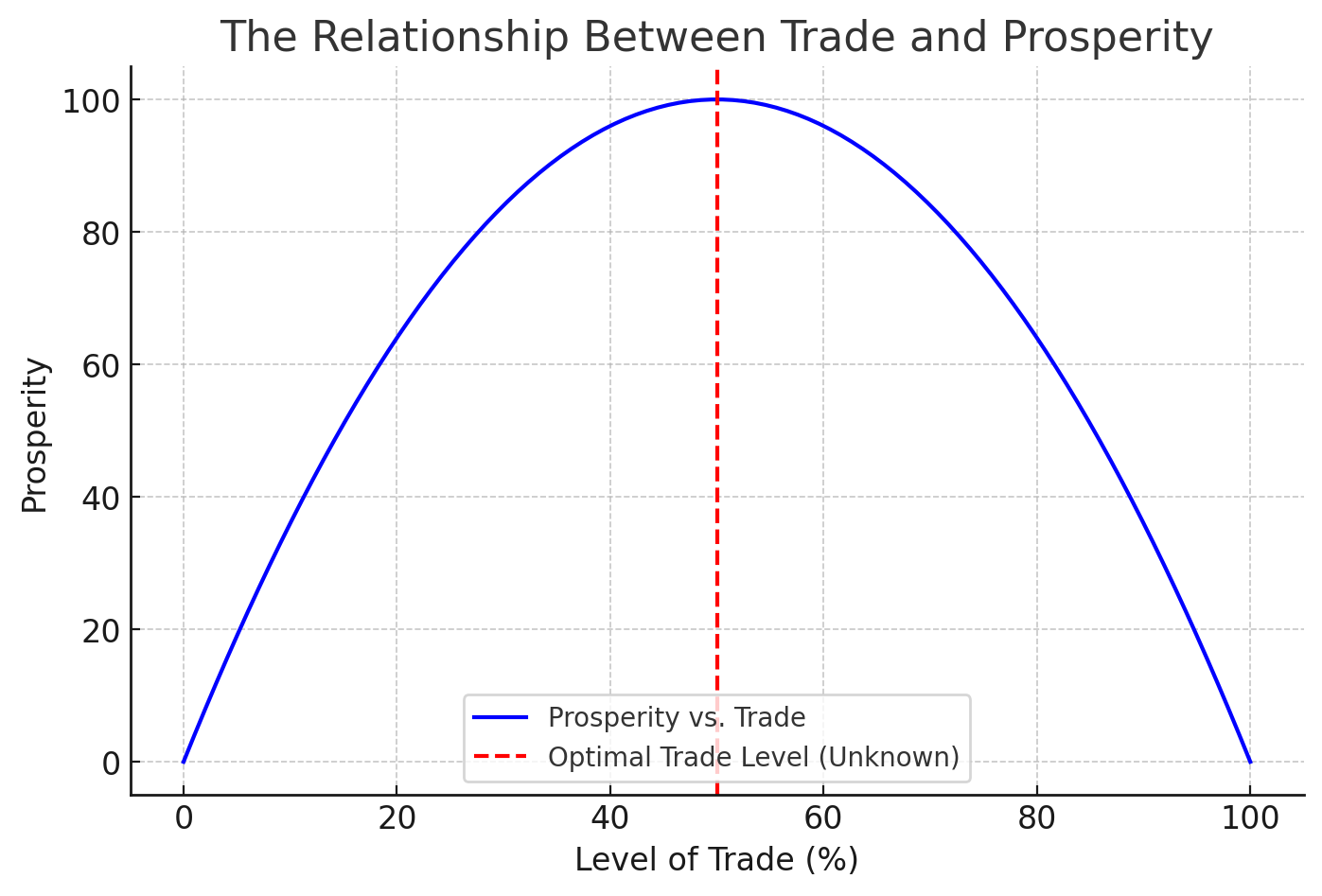

To know the optimum amount of trade is a complex calculus. Even knowing which way to go - more or less trade - requires understanding where we are on the optimization curve. We don't know that. So we don't know if we're fighting against something that could make us a better, stronger, healthier, and more resilient country in the long run. The economic concept of comparative advantage (rather than absolute advantage), and the primacy of 'efficiency' has driven us to this point in globalist trade. But Trump has the power to do what he's doing because there's a real sense, beyond the lyrics of 1980's Bruce Springsteen songs, that something important, as humans, has been lost in the race for globalist economic efficiency.

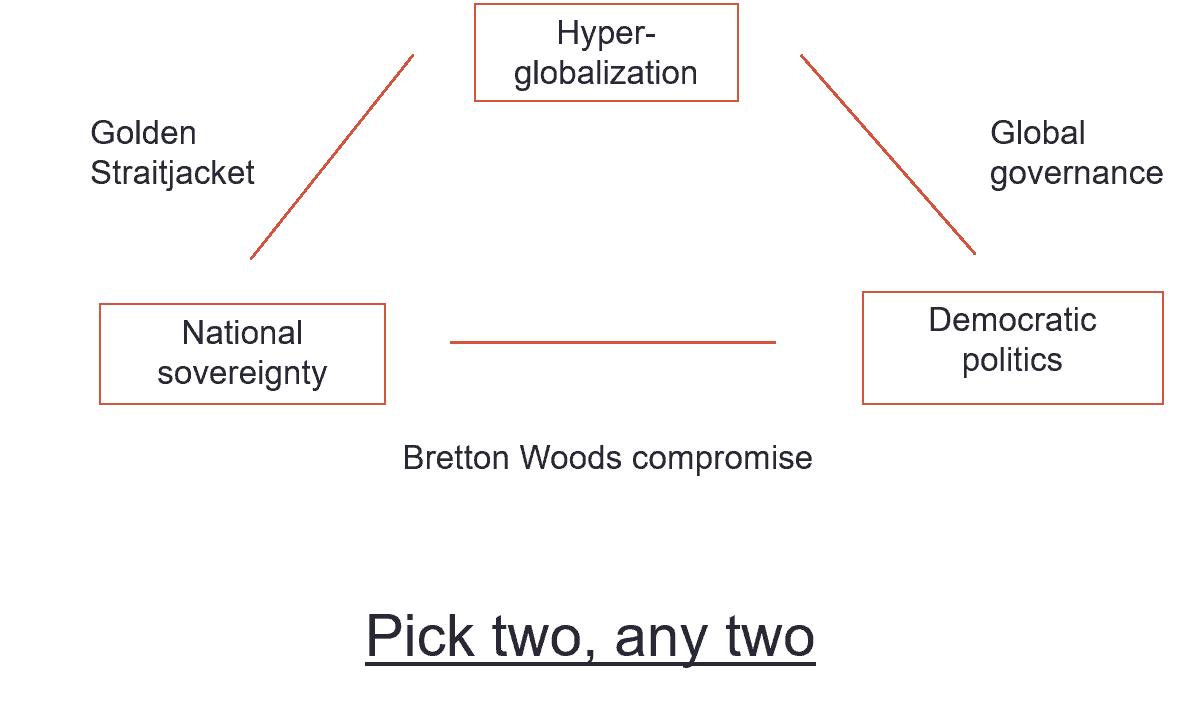

The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy by Dani Rodrik challenges the conventional wisdom that unrestrained globalization leads to universal prosperity. Instead, Rodrik argues that there is an inherent tension between globalization, national sovereignty, and democracy—what he calls the "globalization trilemma." According to this framework, countries can only achieve two of these three goals at any given time: deep economic globalization, strong national governance, or democratic accountability. Pursuing all three simultaneously is impossible.

Rodrik critiques the idea that global free markets are always beneficial, highlighting how international economic integration often comes at the expense of domestic stability and political self-determination. He demonstrates how historical economic success stories—such as the rise of the U.S., Japan, and China—relied not on extreme free trade but on strategic government intervention, protectionism, and policies tailored to national interests. The book warns against the dangers of excessive global governance, which can undermine national policies and fuel populist backlash.

Instead of radical globalization, Rodrik advocates for a more "pragmatic globalization," where nations retain the ability to manage their economies based on local priorities. He proposes a system that allows for regulated trade and capital flows while giving countries room to set policies that protect their workers, industries, and democratic institutions. The central argument is that economic globalization should not come at the cost of national democracy and self-rule—rather, a balance must be struck to ensure that global trade serves the interests of people, not just markets.

SIDEBAR: Chrystia Freeland’s proposal for a 100% tariff on Tesla isn’t leadership—it’s performative politics at best, and petty, self-defeating, and likely illegal at worst. Tariffs are supposed to be a strategic tool in trade negotiations, not a blunt instrument for political point-scoring. Slapping a 100% tariff on a single company reeks of vindictive policymaking, not an economic strategy. It undermines Canada’s reputation as a rules-based trading partner.

And for what? To take a personal swipe at Elon Musk? This isn’t industrial policy; it’s Twitter beef turned government action.

And politically? It’s an embarrassment. Freeland’s move smacks of desperation, possibly to bolster her credentials with the anti-Musk crowd or the union vote. But in doing so, she has revealed a lack of real leadership and economic vision— hopefully a disqualifying trait for anyone seriously eyeing the Prime Minister’s Office. Canada needs a leader who understands economic strategy, trade leverage, and long-term industrial policy, not someone who governs by grudges and grandstanding.

The Tariff War and the Human Cost of Globalist Efficiency

Remember in the din of all this you as much as anyone are in a position to know and act. You are at the front line. You can see and feel the impacts of all this as well as anyone.

One of the worst things about this tariff business is that suddenly, everyone is an economist, a patriot, and a zealot all at once. Social media is burning with hot takes, righteous indignation, and half-baked theories about trade, sovereignty, and economic warfare. For an already far-overburdened and under-inspired public, adding another round of political hysteria to the mix is hardly a welcome development. But before deferring to the chorus, let’s pause to consider three questions that provide a clearer lens through which to view this moment—three mental models through which a social science like economics can really be seen by anyone.

Is This a Big Number?

The first and most overlooked question in any economic policy discussion is the simplest: Is this a big number?

A tariff on Canadian goods sounds dramatic, but what does it really amount to in the grand scheme of things? Canada’s total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) last year was over $3 Trillion! A 25% tariff on $155 billion of that is, by definition, $38.75 billion— about $56.3 Billion - about 1.88% of Canadian GDP. Mere decimal dust in the total economic relationship. Canada is not a banana republic whose entire economy hinges on a single export crop. We are a diverse, complex, and highly integrated economy with the United States. Some industries will feel the sting, but at a macro level, this is not a seismic event. And maybe we should be making more of this by ourselves, and for ourselves.

So why the hand-wringing?

Because economic policy is never just about numbers. It is about perception. A small tariff signals bigger shifts: a recalibration of the U.S.-Canada relationship, a warning shot to industries too reliant on unbridled free trade, and an unsettling reminder that we are not in control of our own fate. The number itself may be small, but the psychological impact—on markets, investors, and policymakers—is larger than it appears.

IS THAT A BIG NUMBER? is by far the best and most important tool you can get out when first confronted with any number or enumerated facts in the media, or any kind of factual argument. Here’s a link to the amazing website and book IS THAT A BIG NUMBER? It also links through to more resources like OUR WORLD IN DATA. It’s all about breaking things down to things and proportions you can get your head around.

Eg: The difference between a million and a billion? It’s the same as inviting 4 people to dinner at your house and having 4,000 people show up.

The Larger, Broader, and Longer-Term Consequences

Harry Hazlitt’s Economics in One Lesson teaches us that the true cost of any policy lies not in its immediate effects but in its long-term, often unseen or unintended consequences. So, what are the broader implications of these tariffs?

First, the economic offset. Tariffs are rarely unilateral punishments. They are adjustments, and markets adjust in response. The Canadian dollar, already trading at a steep discount to the US dollar may weaken slightly more, softening the blow to exporters. The U.S. consumer—who ultimately pays the price for tariffs—may look elsewhere for cheaper goods. Canadians may look elsewhere or start to buy more of their own stuff too. Trade routes may shift, suppliers may adapt, and the net effect may be smaller than the headlines suggest.

But there is a deeper shift happening here: the slow unwinding of globalization. For decades, Western economies pursued efficiency at the expense of resilience. Comparative advantage dictated that if China could make it cheaper, China should make it. If Mexico could assemble it faster, so be it. And if Canada could process America’s raw materials into finished goods, everyone won—until they didn’t. The drive for efficiency led to fragility. We hollowed out domestic manufacturing, offshored critical industries, and built supply chains stretched across a geopolitical minefield. The Trumpian tariff war is not just about economics. It is about reversing a decades-long trend and restoring some level of national self-reliance.

Will this be good for Canada? In the short term, no. In the long term? It depends on whether we choose to fight against the tide or find ways to make it work for us.

All Lines Are Curves: The Limits of Efficiency

This brings us to the final, and maybe most important, consideration: Where are we on the curve? In my opinion, the notion that ALL LINES ARE CURVES may be the most important insight a person can have about the world and how it works.

For years, the assumption has been that more trade is always better. That zero tariffs, zero barriers, and maximum integration create the most prosperity. But is that true?

In physics, in economics, in human experience, there is no such thing as an infinite good. Even efficiency itself is a waning good. Diminishing marginal returns apply everywhere. A nation with zero trade is stagnant and poor. A nation that relies entirely on external trade is equally vulnerable, utterly dependent on the whims of foreign powers. The optimal level of trade—the point of balance—is somewhere in between. The question we must ask is: Have we overshot?

It is entirely possible that a slight retreat from globalization is exactly what Canada needs. Not to embrace autarky or economic nationalism, but to recognize that efficiency at all costs has its costs. The cheapest supply chain is not necessarily the best. The most frictionless trade deal is not necessarily the strongest.

This is where economics meets human nature. The invisible hand may optimize for cost, but it does not optimize for community, identity, or national resilience. For decades, we’ve been told that globalization was an unstoppable force—that it made everyone richer, happier, and more connected. But did it? Many people have a sense something is wrong. Out of balance. By the standard measures, we have growth. But where is the prosperity that growth is supposed to bring? Why would we want growth without a broad-based increase in prosperity for all households?

Trump’s tariffs, and the broader retreat from globalist economics, exist because millions of people believe that something important was lost in the great economic shuffle. Not just in factories and steel towns, but in culture, identity, and community. The economic arguments may say one thing, but the lived experience of many suggests another. The backlash to globalization is not just about money—it is about meaning.

The Tariff is Not the Story

So, should we panic about these tariffs? No. Should we ignore them? Also no. But what we should do is use them as a moment of reflection.

Not every act of protectionism is foolish, and not every free trade agreement is wise. The economic models we’ve relied on for decades are not gospel, and the people who championed them are not infallible. We are entering a period of economic correction—a realignment that seeks to balance efficiency with resilience, cost with sovereignty, and trade with national strength.

A policy where everyone loses—where businesses, workers, and consumers all suffer without a clear gain—is not strategy, it’s stupidity. If an action weakens both sides, draining resources, trust, and stability, then it serves no purpose beyond self-inflicted harm. True leadership seeks balance, not mutual destruction.

Canada’s challenge is not to fight this trend but to navigate it intelligently. The goal should not be a desperate return to the pre-2016 order but a strategic adaptation to a new reality. What do we need to make domestically? What should we let go of? What vulnerabilities have we ignored for too long?

Trade wars are the economic equivalent of bar fights—messy, impulsive, and often leaving both sides worse off. While Trump’s tariffs have sent the usual voices into a spiral of hysteria, labeling them the worst thing to ever happen to Canada, history suggests a cooler head and a longer view serve us better. Economic nationalism, when wielded wisely, isn’t about chest-thumping retaliation but about strengthening our own position.

As Justin Trudeau goes into the boxing ring with Trump this morning mostly for show I think***, Pierre Trudeau, his father faced with Nixon’s economic sucker punch in the ’70s, didn’t launch a tariff war—he pursued the “Third Option,” looking beyond the U.S. to build new trade relationships and reduce dependence on an unpredictable partner. That’s the playbook Canada should dust off now. And we should do what many like us in America can’t - look beyond the bluster, hyperbole, and lies of Trump’s speech (and tweets) to understand the fundamental truths, the struggles of real people, that give him such power. Rather than slapping on retaliatory tariffs that only hike prices for our own people, the smarter move is investing in domestic industries, energy independence, and trade diversification. The U.S. will always be our biggest trading partner, but it doesn’t have to be our only one. If we’re going to pick a fight, let’s save it for a battle that’s righteous and winnable—one where we’re not just reacting, but shaping our own economic future.

It’s Our Home Economics We Should Be Concerned With More So Than Our Trade Economics

And most importantly, we must remember that neither corporations nor governments are the true foundation of any economy. It is the household—the individual, the family, the small business owner—that ultimately determines the fate of our economy. Household consumption typically comprises around 60% of GDP. And it’s always worth noting (see related below) that that’s also where babies come from - meaning that is what the future is actually built on not globalized free trade of automobile parts. International trade policies and corporate strategies may shift, but the resilience and choices of Canada’s households and their beliefs will shape our future prosperity far more than any tariff ever could.

The tariff is not the story. The larger question is whether we are prepared to rethink our economic assumptions—and whether we will be better for it in the end.

RELATED: Where Do Babies Really Come From?

It's Not Capitalism That's Bad - It's That We're Bad Capitalists

Let’s put it bluntly: Nova Scotia has a choice. We can either continue as the economic colony we’ve been for centuries—digging, cutting, and hauling away our raw materials for others to process and profit from—or we can step into the future, creating wealth here at home by adding value to what we produce.

RELATED: What would Wendell Berry Do?

What Would Wendell Berry Do?

Wendell Berry, a Kentucky farmer, writer, and thinker, blends economics, philosophy, and poetry to remind us that in times of economic trouble, true resilience comes from households that believe in the future, strong local economies, meaningful work, and a deep connection to place.

*** In fairness to Justin Trudeau his speech was well done, filled with facts the American media apparently did not have and he got them through, and if he near brought me to tears we can bet his words, to the extent they were heard resonated with Americans.

The New York Times reported this morning part of Mr. Trudeau’s speech addressed Mr. Trump’s claim that Canada is responsible for a major influx of fentanyl and irregular migrants into the United States. In response, Mr. Trudeau presented recent data showing that only about 1 percent of fentanyl in the United States originates in Canada. He also said that about the same percentage of irregular crossings into the U.S. occur at the northern border.

But he also focused on the historically close ties between Canada and the U.S., including military cooperation in two world wars as well as the Korean War and the war in Afghanistan. “From the beaches of Normandy to the mountains of the Korean Peninsula, from the fields of Flanders to the streets of Kandahar, we have fought and died alongside you during your darkest hours,” he said.

Yes to much of this, so long as it is really about how our two countries engage in trade and the relative merits of protectionism. I am more concerned about the deeper subtext to what is happening in the US, as seen in the administration’s overall approach to Canada, Mexico, Panama and Greenland. We cannot dismiss that TruMusk’s pusposes may not be about ‘the deal’ but rather the acquisition. Much of the popular reaction is, justifiably I think, energized toward mitigating our exposure to Trump’s stated goal of economic annexation. If it was ‘only’ about trade deficits, globalization, etc, I’d be more comfortable with your measured approach.

I think "we" must fight the tariffs with both hands by making & buying Canadian AND making sure that through our government responses US citizens get the message of how wrong their leader is. The broader global trade question is legit as well. Like everyone else, Canadians want everything, all the time, super-sized, and we want it cheap! We have become entitled. And have chosen to ignore and deny the socio-economic, environmental and health (including mental) costs. So there is a lot of room for backing up, taking stock, seizing this opportunity to do better.