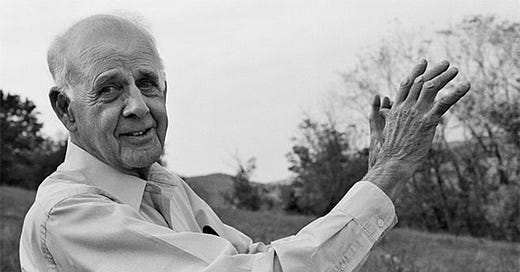

What Would Wendell Berry Do?

Ultimately, Berry would see the tariff debate as a distraction from the real issue: we have become too reliant on distant, faceless systems to meet our most basic needs

Wendell Berry, a Kentucky farmer, writer, and thinker, blends economics, philosophy, and poetry to remind us that in times of economic trouble, true resilience comes from households that believe in the future, strong local economies, meaningful work, and a deep connection to place.

Wendell Berry is a poet, novelist, essayist, and lifelong Kentucky farmer who has spent decades critiquing industrial capitalism’s impact on communities, agriculture, and the environment. Unlike traditional economists, he weaves literature, philosophy, and practical farming experience into a vision of an economy that values people, households, land, and local self-reliance over blind efficiency and globalization. He warns that when economies become too dependent on distant markets and centralized control, they lose their resilience—leaving individuals and communities powerless in times of crisis. As the modern world faces economic uncertainty, Berry’s wisdom urges us to rethink where true security comes from: not from global supply chains or government policies, but from our ability to build strong local economies, sustain real craftsmanship, and create meaningful, place-rooted work.

Ever the champion of local economies, agrarian values, and human-scale communities, Wendell Berry would likely cast a skeptical eye on both the free-trade evangelists and the protectionist firebrands in the latest U.S.-Canada tariff skirmish. His response wouldn’t be a simple economic analysis; it would be a meditation on the deeper consequences—social, ecological, and moral—of an economy unmoored from place, responsibility, and the dignity of work.

The Work of Local Culture:

“If the communities and their economies are to last, they must be built, like the natural world, to be self-sustaining. The great enemy of freedom is the alignment of political power with wealth. This alignment destroys the commonwealth—that is, the natural wealth of localities and the local economies of household, neighborhood, and community—and so destroys democracy, of which the commonwealth is the foundation and practical means.”

Berry has long argued that globalization, with its relentless pursuit of efficiency and cost-cutting, has severed people from the land and each other. In his view, modern economies don’t exist to serve communities but to serve corporate and political interests, treating people as little more than disposable labor and consumers. The household is denied its place at the centre of the economy. It works in service of government, corporations, and globalized trade instead of the other way around. A trade war, in this light, is not a battle of economic ideologies so much as a symptom of a broken system in which both sides are fighting to control an unsustainable machine.

On tariffs specifically, Berry might remind us that merely tweaking the levers of trade policy won’t restore what has been lost. He would question whether a sudden embrace of economic nationalism - the other extreme - can undo decades of disinvestment in local economies and rural communities hollowed out by the pursuit of cheap goods and cheaper labor. Protectionist policies may provide short-term relief to certain industries, but they do not address the deeper issue: our economic lives have been outsourced, not just in terms of production, but in terms of responsibility. We have surrendered our ability to provide for ourselves in any meaningful way.

Berry’s prescription wouldn’t be a trade deal or a tariff but a return to subsistence and sufficiency—not in the sense of rejecting trade altogether, but in recognizing that true economic health starts locally. He would urge Canadians and Americans alike to rebuild strong regional economies, grow more of their own food, produce more of what they consume, and value work not just as a means to a paycheck but as a fundamental expression of human purpose. “The global economy,” he might say, “has no allegiance to place, and where there is no allegiance to place, there is no community.”

Ultimately, Berry would see the tariff debate as a distraction from the real issue: we have become too reliant on distant, faceless systems to meet our most basic needs, and until we reclaim responsibility for our own economic well-being—through land stewardship, local enterprise, and small-scale resilience—no trade policy will save us.

I ran into friend Linda Best, originator and managing-director of FarmWoks Investment C-op @ Lunenburg Farmers Market this morning. FarmWorks is all about this substack subject, the need to relocalize essential goods & services. FarmWorks has done a great job in a short time. The org connects ambitious people with great and often new ideas for food production with capital from a broad range of small, local investors. FW does an amazing job of getting around the Province, soliciting loan proposals & then rigorously selecting, vetting & coaching the proponents AND finding investors to fund the projects. Follow through is thorough and pay-back has an astonishingly good record. Awesome. But, as Linda pointed out this morning, NS is still only producing (and eating) 10% local. It was something like 65% 60 years ago. A combination of market forces and government decisions to prioritize export production and efficiencies of scale over local sufficiency are a couple of the misdirections that brought us to this vulnerable position. Relocalization of food production and processing is totally possible in Nova Scotia and would be better for the health of the consumer, the environment, the economy and the climate.