Zodiacs, Killers, and Green Peace

They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; These see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep.

As the large Soviet factory ship, harpoon gun poised to fire, loomed over a whale immediately below the bow, Rex Weyler struggled with his camera fighting wind, waves, the stench of the Soviet harpoon ship, and the migraine sea sickness only those trying to focus an eye through a camera while being tossed by the sea can know.

Weyler was among the early members of Greenpeace who met in Canada during the early 1970s. Many of them, including Weyler, had left the US to escape being drafted for the Vietnam War. "It's so hard to imagine today but at that time there was no ecology movement," he remembers. "There was the peace movement, the women's movement, the civil rights movement, and we felt there needed to be a conservation movement on the same scale as those."

Catching the whales on camera was the biggest challenge Rex explained to a BBC interviewer years later. In some ways the story, and the subject were too big to film. A common problem in visual storytelling. "They were being chased by harpoon boats so they would rise to the surface, breathe out, breathe in, and dive again." There wasn't much to photograph, Weyler adds, until the whales had been hit by a harpoon.

"My awareness was mostly focused on exposure, shutter speed, those things," he says. It was only after he'd put down his camera that what he had witnessed hit him.

"It was devastating. We had never seen anything like it. We saw [the whaling boats] harpoon whales, there was massive amounts of blood in the water, and whales flapping and splashing as they struggled and then died.

It was only days later in the dark room Rex knew he got the photographs.

They were images that changed the world and marked the beginning of Greenpeace's "mind bomb" campaign.

The Sea Far Away

The ocean has always been a faraway place. Through all of human history. Even the story itself, the hero’s journey famously identified as the universal myth by Joseph Campbell, probably evolved from seafaring cultures — almost all of our ancestors have lived within a day’s walk from the sea. We’ve always depended on stories of the sea to create our understanding of the thing. Before Greenpeace, and Earth Day, before Rex’s photo whaling was the story of Moby Dick. A world where the whales were the giant and dangerous goliaths, and the men who risked everything to bring them in were proud seafarers battling giants.

In the 1950’s and 60’s when Jacques Cousteau was still thought of as an “Inventor”, “Adventurer” and “Filmmaker”, approximately 80,000 whales were being hunted every year. Hunting technology had advanced, and whalers had harpoons and catch ships that could outrun whales.

Despite various whaling protection measures being introduced, including the International Agreement of the Regulation of Whaling in 1937, some countries, such as Russia and Japan, ignored them and caught whales illegally. Between 1900 and 1999, an estimated 2.9 million large whales were caught and killed by the industrial whaling operations, although the actual numbers are believed to be much higher.

By the 1950s and 60s, the rapid decline of whale stocks worldwide was clear. Canada was among the first nations to take notice. Hunting Blue Whales was banned in the North Atlantic in 1954. At least as far as fisheries managers were concerned. It took Canada almost another 20 years to effectively stop commercial whaling in our waters.

The federal government closed the last whaling station in Canadian waters in 1972 and placed a full moratorium on commercial whaling. After four centuries of slaughter, the killing stopped.

The last two Canadian onshore whaling stations in Williamsport and Dildo, Newfoundland, were closed. Between 1967 and 1972, 1,248 whales were killed there, pothead, minke, fin and sei whales, their oil and meat exported to Japan. In just five years, Canada’s last commercial whaling venture produced 33,000 barrels of oil. The whaling stations, built in 1945 and supported with government and Japanese investment through the 1960’s, were the final active remnants of an industry that had once defined the Atlantic.

When it closed in 1972, Williamsport became a ghost town.

And the sea was no different.

The Gulf of St. Lawrence had been the deadliest place on earth for whales.

The Gulf had been a whale magnet for millennia. Its unique mingling of cold Labrador currents with warmer waters from the Atlantic created an upwelling of nutrients that fed a buffet of life—krill, capelin, herring, plankton—and drew in the great cetaceans.

The Basques were the first Europeans to arrive, hunting right whales in the 1500s. Over the next 400 years, Dutch, French, English, Scottish, Norwegian, American, and eventually Canadian whalers all took their share. Blue whales, humpbacks, fin whales, and minkes. Even belugas in the St. Lawrence estuary were harvested by the thousands.

By the 1970s, the whales were nearly gone. Right whales were considered functionally extinct in the Gulf. The great blues—Earth’s largest animals—had fallen silent. Humpbacks and fins were rare sightings. The nursery was closed. The Gulf had become a graveyard.

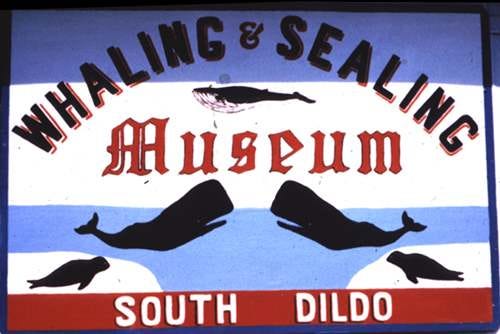

Dildo went on to open a whaling heritage museum, and 30 years later, began what is now a thriving whalewatching tourism industry that probably brings more money, and certainly more joy to Dildo than whaling ever did.

50 years of fighting for the planet

This next week marks the 50th anniversary of a moment that changed the world—and changed me.

At the end of June 1975, the first Greenpeace photos of industrial whaling were released. Their direct action on the high seas cracked open the conscience of a generation. It was the end of commercialized whaling—and the beginning of a new way of looking at the ocean as something sacred.

For many of us, it was also the dawn of a new way of caring about the world.

But the work is not done. In truth, it’s barely started. Somewhere along the way, the original awe of that first Greenpeace summer got tangled in the politics of protest. The spirit that called us to protect was slowly overtaken by the fight with government, industry, and all the people who simply weren’t ready to see what they were doing.

In truth, over the last 50 years we’ve learned little about the ocean and how it works. And the fight has devolved into something… unproductive. Most of the ocean is still unexplored and unmapped in any meaningful modern way. We have better maps of Jupiter’s moons than much of our own ocean.

That Greenpeace mission in 1975 changed lives. It lit a fire in the hearts of those who saw it. And whether they know it or not, most of the progressive, leftist, social justice folks in your life today—young or old—owe something of their philosophy to those Greenpeace zodiacs.

SIDEBAR: The Zodiac

Its inflatable pontoons and rigid floor make it stable, buoyant, and nearly unsinkable—even in rough seas. It can be rolled up for transport and inflated in minutes. Easily carried by hand, launched from a beach, and powered by a small motor, yet it handles like a much larger vessel. Used by navies, explorers, scientists, and activists, it became the boat of choice for people who needed to get close—to danger, to discovery, to the real edge of the world.

But what really sets the Zodiac apart is the way it feels glued to the sea. With its shallow draft, it floats on the water rather than in it—skimming over reefs, river mouths, and ice floes where deeper boats would run aground. At the same time, its wide inflatable tubes give it a low center of gravity and enormous surface contact, making it surprisingly stable even in rough water. It doesn’t fight the sea—it flows with it. A Zodiac doesn’t plow forward like a traditional boat; it dances, it flexes, it responds.

In those 1970’s summers I wanted a Zodiac so badly. Not a yacht, not a schooner, not a sailboat—just that little rubber raft with the heart of a sea lion. To my kid mind, a Zodiac wasn’t a boat, it was a vessel—the kind you launched into history with. I thought if I just had the zodiac, I could also adventure, explore, discover, and change the world. It was all potential: unmoored, untethered, unstoppable. I didn’t just want a boat—I wanted a cause, an adventure, a mission, a world to discover. And the Zodiac looked like it could carry it all.

By the 1960s and '70s, it became the signature craft of Cousteau's Calypso crew and the symbol of real-world exploration. Of course Greenpeace adopted them too—those first fearless missions against whalers were waged from the tubes of old-school Zodiacs. They were tools of conscience. They could land on Antarctic ice, skirt oil spills, or drift silently beside a breaching whale.

Fifty years later, a lot has changed. On land.

This June, the media reveals that in the waters off Sicily, the Sea Shepherd crew is still at it—tracking and reporting illegal fish aggregating devices (FAD’s): junk rigs made from garbage and old gear hung from the seafloor, catching whatever indiscriminately and often pointlessly as the gear is lost and drifts.

Here at home, off Nova Scotia, the waters are a battlefield. But I can't even call it illegal fishing—because no one agrees on what the laws are, or how to enforce them.

Out of sight of land still means outside the law.

Seabillies set their own rules in a wild-wild East.

Around Nova Scotia and up into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, whales—fifty years after Canada’s last clunky moves to end commercial whaling—are making a tentative comeback.

But new threats are everywhere.

Tons of ghost gear drift unseen. Sea bottoms are shredded by bottom-dragging trawlers—cutting down the trees just to get the apples the euphemistically call a harvest. Giant ships plow through whale waters at speeds no whale can outrun. Smaller boats race even faster to be first, chasing fish and lobster to get a few cents more at the dock. All of it, just to get to the bank and the biggest pickup their catch can buy.

The Sea Will Take It Away (But It Doesn’t)

Garbage: An estimated 11 million metric tons of plastic enter the ocean every year—equivalent to a garbage truck every minute. At current rates, that could triple by 2040.

Sewage: Over 80% of the world’s wastewater is discharged into the ocean untreated. Coastal dead zones, caused by nutrient runoff and sewage, now cover more than 245,000 km²—an area larger than the UK.

Bombs & Munitions: After WWII, Allied nations dumped millions of tons of unexploded ordnance, chemical weapons, and toxic waste into the sea. The U.S. alone dumped at least 64 million pounds of nerve and mustard gas in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico.

Sunken Ships & Toxic Wrecks: The ocean holds over 3 million shipwrecks, many still leaking oil, fuel, and radioactive material decades later.

Oil & Industry Waste: In addition to dramatic spills, everyday shipping and offshore drilling contribute millions of gallons of oil, heavy metals, and industrial waste to marine ecosystems annually.

The myth that “the sea will take it away” has justified centuries of dumping. But the truth is, the sea remembers everything—and now it’s washing it all back.

What Lies Beneath

The sun glances off the sea surface, creating a sense of beauty, mystery, awe.

But it hides more than it reveals.

Even in Nova Scotia, a place of the sea if ever there was, few among us have ever been to sea in any meaningful way—out of sight of land. Fewer still have seen, or even wondered what lies beneath.

What lies beneath?

We search the stars for life. Scan a thousand light-years in every direction. And in all that vastness, we’ve found nothing—nothing—that compares to the ocean.

The ocean is where, as far as we really know from observation, life began. Where life still gathers in unimaginable abundance. It covers most of our planet, shapes our weather, feeds our world, and pulses with creatures so strange they might as well be alien.

Jellyfish older than the rings of Saturn. Squid that speak in flashes of colour. Blue whales the largest animal to ever exist in the galaxy as far as we know. If we found it in space you would never hear the end of it.

And yet, in the ocean… how much does your kid know about the largest creature to ever live in the galaxy?

SIDEBAR: Blue Whale — The Leviathan of Our Time

The blue whale is our planet’s living leviathan—a creature so vast, so quiet, and so improbable it feels more like myth than biology—ancient, immense, and humming through the depths like a forgotten god.

Largest Animal Ever

The blue whale isn’t just the biggest animal alive today—it’s the biggest animal to have ever lived on Earth. Bigger than any dinosaur.

Heavyweight Champion

An adult blue whale can weigh up to 200 tons—about the same as 33 elephants or 2,500 humans.

As Long as a Plane

They can grow up to 100 feet long, roughly the length of a Boeing 737.

Heart the Size of a Motorcycle

Their heart weighs around 400 pounds and is so large a human could crawl through its arteries.

Loudest Voice in the Animal Kingdom

Their calls can reach 188 decibels—louder than a jet engine—and can travel over 1,000 miles through the ocean.

Diet? Microscopic. Appetite? Colossal.

They eat krill, tiny shrimp-like creatures. During feeding season, a blue whale consumes up to 4 tons of krill a day—that’s about 40 million individual critters daily.

Born Big

A newborn calf is about 20 feet long and weighs 2–3 tons at birth—and it gains 200 pounds a day on its mother's milk.

Surprisingly Swift

Despite their size, blue whales can swim up to 20 mph in short bursts.

Migratory Marvels

They undertake epic migrations, traveling thousands of miles between feeding grounds in polar waters and breeding grounds in the tropics.

Blue Whale Brain: Size vs. Function

The blue whale’s brain weighs around 15 pounds (6.8 kg)—about five times heavier than a human brain.

Blue whales have well-developed auditory and social processing areas, especially for interpreting low-frequency sound across vast distances.

While blue whales are intelligent, their intelligence is not like ours—not tool-based or technological. It's deeply sensory, acoustic, and perhaps emotional or social in ways we don't fully understand.

They sing. They travel. They communicate. They remember.

But their minds operate at a different frequency—measured in ocean-sized distances and glacier-paced time.

So yes, their brain is massive—but it doesn’t make them thinkers like us.

It makes them listeners, navigators, and maybe poets and storykeepers of the deep.

Nearly Gone, Slowly Returning

Blue whale populations were decimated by 20th-century whaling. From over 300,000 to just a few thousand. Today, thanks to protection efforts, they are making a slow, fragile comeback—a living symbol of what we’ve nearly lost, and might still save.

The Sea Close By

We dream of water on Mars while dumping poison into the Pacific and have to be held back by law, and increasingly the threat of violence, from fishing the last salmon, eel, tuna, swordfish, or lobster from the sea . We fantasize about Europa’s hidden sea while knowing almost nothing about the one that surrounds us. Ninety-five percent of Earth’s ocean remains unexplored.

More people have walked on the Moon than have visited its deepest trench.

We live on a blue planet, in a universe of dry rock and fire.

Earth’s ocean is not just rare—it may be the rarest thing in the universe.

We’ve searched a thousand light-years in all directions, and still, nothing compares.

We scan the heavens for a second Earth.

But maybe we haven’t even finished discovering the first one.

"The Sea Close By" (La Mer Proche) is not so much a book but a thought —a short, radiant essay by Albert Camus that serves as both a love letter to the Sea and a quiet rebuke to existential despair. Written in the 1950s, it stands apart from his more austere philosophical works by embracing beauty, sensuality, and presence as forms of meaning.

At its heart, The Sea Close By is a meditation on the idea that beauty can be a form of truth, and that being alive to the world—through the senses, through nature—is itself a form of resistance.

It is Camus’ gentle argument that the absurd is not only found in suffering, but also answered in wonder. The sea offers no answers, but it grounds us, cleanses us, and draws us back to the moment. It’s a quiet, sunlit philosophy: not of salvation, but of presence.

“I grew up with the sea and poverty for me was sumptuous; then I lost the sea and all the rest.”

— Albert Camus, The Sea Close By

Back To The Garden

Today, researchers have documented the regular presence of 13 species of whales and porpoises in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. These include:

Blue whales, with perhaps only 250 individuals in the North Atlantic population, returning to known feeding areas near the Mingan Islands and Anticosti.

North Atlantic right whales, critically endangered and shifting their migratory and feeding routes into the Gulf, likely due to warming waters and prey redistribution.

Humpback whales, now common sights off Percé and the Gaspé coast.

Fin, minke, pilot, and sperm whales, re-establishing migratory and feeding patterns.

Belugas, still in recovery but breeding in the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park.

And more recently, sightings of Sowerby’s beaked whales and white-sided dolphins.

This isn’t just ecological restoration—it’s cultural memory. The whales are returning to places their ancestors once knew.

And maybe the very form of our activism—our storyline of good versus evil—is holding us back now.

Have we been so focused on protest and outrage that we’ve lost the thread of stewardship? Have we grown too attached to conflict to collaborate?

Can we recover the original spirit—not of grievance, but of awe?

How can we change the story?

On June 29th, ORRCA Australia is celebrating a Whale Census Day.

How can we rise beyond the old scripts and work together toward the better world we all know is possible?

Because beneath the surface, all the mystery of the galaxy waits and whispers, lost and hidden. And what lies beneath… is everything.

The Sea and The Wind That Blows

E.B. White knew it. The old explorers knew it. Cousteau knew it. And somewhere, the youth in all of us still knows it too—that if we only had the Zodiac and the courage to launch, we could find it again. The great adventure isn’t out there among the stars. It’s just off our foreshore.

There’s every reason in the world for us to get out there and look. Not for yachting pleasure, not for fishing, not for Instagram, but to live with and bear witness to the waters that made us — reestablish our connection with it, and explore our sovereignty as citizens of the sea.

Psalm 107:23–30 (KJV):

They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters;

These see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep.

This passage is both a literal description of life at sea—with all its terror, awe, and unpredictability—and a metaphor for the human condition. Those who "go down to the sea in ships" are portrayed as brave and vulnerable, exposed to the raw power of nature, and through it, the divine.

It’s been used for centuries as a tribute to sailors, explorers, and anyone who dares to venture into the unknown, whether ocean or soul.

Please support Greenpeace financially. The fight goes on: to stop the vacuuming up of krill which is a major food of whales. It is vastly overexploited in the Anctarctic and used in mass production krill oil tablets for rich countries. STOP IT!