Why the Greenest Building is the One That Lasts

Architecture is a violent business. You need to cut, dig, extract, and crush. All the tech and tricks the hucksters can sell can never make a disposable building green.

If you’ve ever stared at a pile of IKEA furniture instructions, feeling the existential weight of particleboard and Allen keys, you’ve confronted one of the 21st century’s dirtiest secrets: planned obsolescence. It’s not just your flimsy bookshelf that’s doomed; entire buildings are constructed with the idea that they’ll be torn down before you can say “net-zero emissions.” But what if we’ve been looking at sustainability all wrong? What if the greenest building isn’t the one with the most solar panels or the highest LEED certification, but the one that’s simply still standing when your great-grandchildren are arguing about holographic wallpaper?

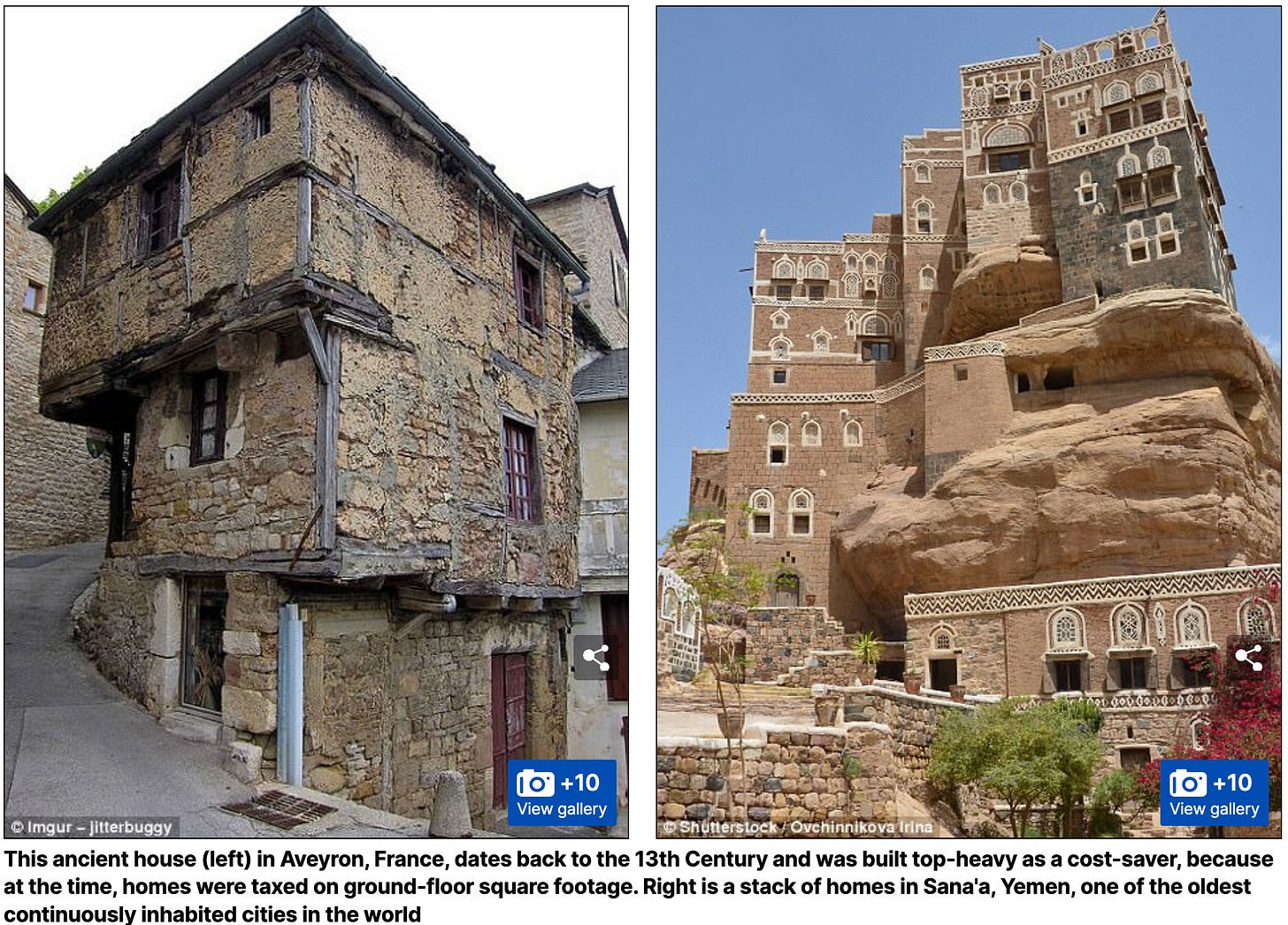

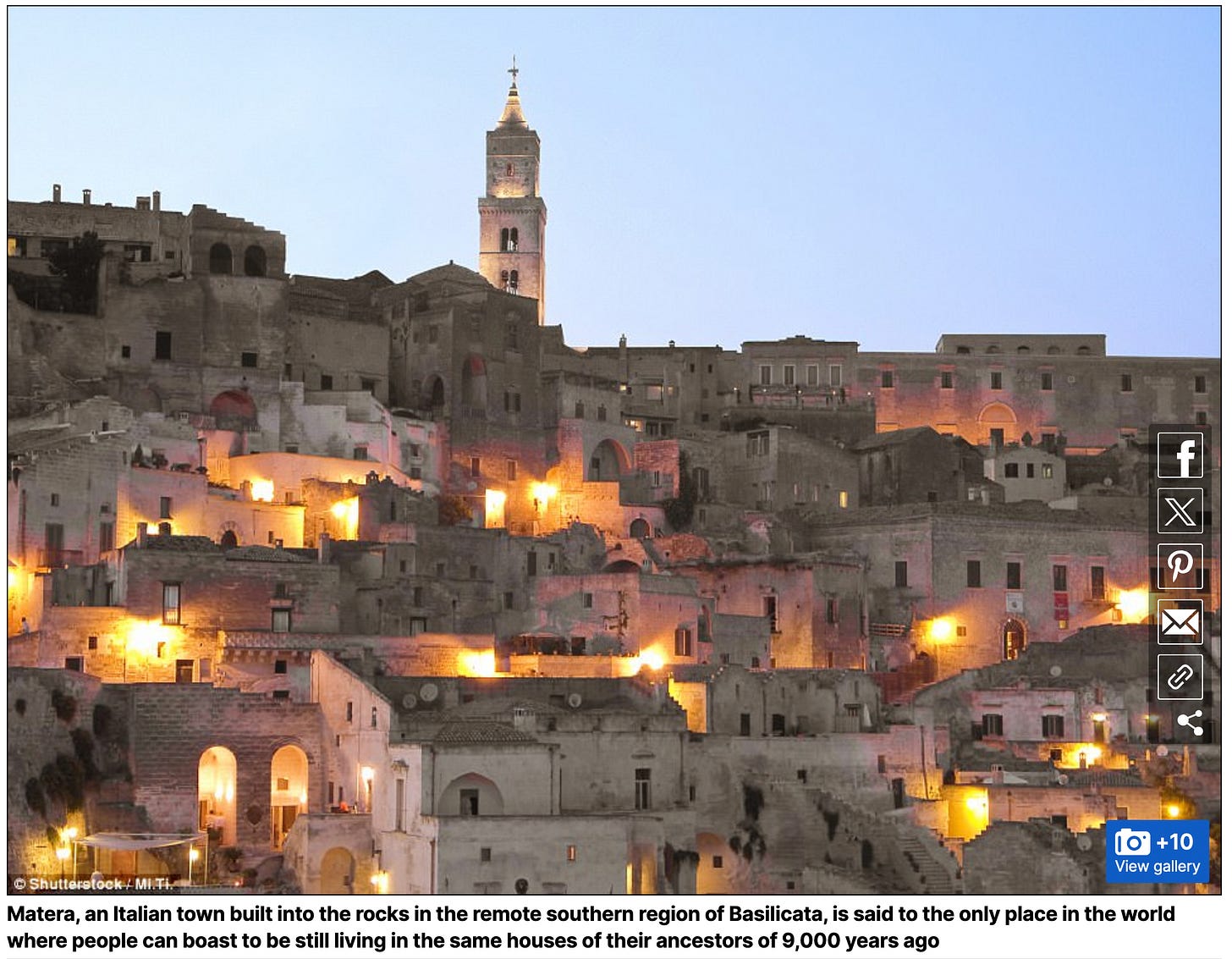

Let’s get weird for a second and think about embodied carbon—a term that sounds like it belongs in a Star Trek episode but actually refers to all the carbon dioxide emissions locked into a building’s bones. From the quarrying of stone to the smelting of steel to the countless trucks idling at construction sites, the creation of any structure is a carbon-heavy affair. The accounting is this: the longer that building stands, the more those emissions, work, and smashing get amortized over time. It’s why mortgages exist - to spread the cost out over the asset’s useful life. If that life is 400 years rather than 40, that 10% extra effort and cost doesn’t seem so bad.

The Myth of the New

We’re acquisitive consumers. In our cultural obsession with the new—new buildings, new gadgets, new TED Talks about mindfulness—we’ve missed the fact that newness often comes with the heavist environmental price tag, and no amount of passive design, net-zero junk tacked on is going to make it anything but worse. Every time a perfectly functional old building gets razed to make way for a glass-and-steel monument to modernity, we’re essentially hitting the reset button on carbon efficiency. Sure, the new building might have triple-glazed windows and geothermal heating, but it could take decades for those energy savings to offset the initial environmental cost of its construction. And that new building doesn’t have the time. It’s not just that it’s made cheaply, out of crappy materials, with shoddy workmanship. It’s not that its extreme modernist style is going to go so embarrassingly out of style that it will lose all its usefulness and interest. It’s just not beautiful, not intended to last, and not able to change with the times.

And that’s if it even makes it to decade three. The modern building industry operates on a tacit assumption: everything is disposable, including the buildings themselves. Developers, at the mercy of architects schooled only in novelty, chase trends like sneaker collectors, throwing up condos with lifespans shorter than your average suburban dog. We’ve traded resilience for immediacy, longevity for Instagrammability, and it’s not pretty.

Waste Not, Build Not

Construction waste: the great, unglamorous elephant in the climate room. The demolition of buildings generates mountains of it—concrete, wood, drywall, glass. Here in Halifax, we add an acidic leeching bedrock stone called pyretic slate. North America alone produces millions of tons of construction and demolition debris annually, most of which ends up in landfills. Contrast this with older buildings, which tend to get renovated, repurposed, and reinvented rather than junked. The materials and craftsmanship of these structures were built to last, not to line the pockets of demolition contractors.

And what about energy efficiency? Here’s the observable reality: older buildings can often be retrofitted with modern systems that rival or even surpass new construction in energy performance. Slap some solar panels on a century-old brownstone, and you’ve got a green powerhouse that’s still around long after your flashy new skyscraper has developed terminal cladding rot.

The Case for Forever

But let’s go long game. Beyond carbon footprints and kilowatt-hours, there’s something profoundly ecological about permanence. A long-lasting building is a monument to restraint. It says, “We’re in this for the long haul.” It values craft over speed, durability over trendiness, legacy over short-term gain. It’s built for the rising generation as much as for us, and when we think that way we do good things.

Buildings that endure often take on a life of their own, becoming part of the fabric of their communities and their future. They anchor neighborhoods, hold memories, and weather generations. They whisper to us about time and continuity, urging us to think beyond our own lifespans. In this way, they’re not just environmentally sustainable but culturally sustaining.

Our Choice

So here’s the pitch: Instead of fetishizing the new, let’s champion the enduring. Let’s build like we mean it, like we’re not just throwing up shelter but creating something that might outlast our grandchildren’s grandchildren. Because in the grand ecological ledger, the longest-lasting building isn’t just a victory for sustainability—it’s a radical act of hope.

IKEA sidebar: They're the largest manufacturer, buyer and retailer of wood on the planet. IKEA's factories consume more than 20 million cubic meters of wood a year. That works out as roughly one tree every second or a great pyramid’s worth a year. The company tells consumers that the wood in its products comes from sustainable forests. But a major investigation by Channel 4 and the environmental organization Earthsight has discovered that some of the wood that ends up in Ikea's most popular products has been cut down illegally. The wood comes from the lush forests of the Carpathian mountains on the border between Ukraine and Romania - where corruption and illegal logging are a big problem and an incentive for war.