Since January 2018 the government of Nova Scotia has been posting a monthly list of the number of people registered to be looking for a family doctor/practice. They also launched a website to encourage people without a family doctor to register.

During the first five years the number registered on the site has tripled, from about 40,000 to over 120,000. That’s 11.1% of the population.

Today, the CBC reports that the list has topped 160,000 people. That’s 16.2 percent of the population.

This single number has become a proxy, a measure, of the quality of health care in Nova Scotia, the state of our health system, and the quality of our lives.

But is it the right number?

Is the media obsession with this single number distracting us from more important problems, bigger ideas, and obvious solutions?

The History of The Family Doctor

The concept of having a personal physician dates back to ancient civilizations. In Ancient Greece, for instance, wealthy individuals often had personal physicians. Hippocrates, known as the "Father of Medicine," and his followers set the foundation for personalized medical care in the 4th century BCE. In Rome, affluent families also had their own physicians, often slaves or freedmen trained in the art of healing.

Historical Development

Medieval Europe: During the medieval period, the tradition of personal physicians continued primarily among the nobility and royalty. These physicians were responsible for the health of their patrons and often lived within their households.

Renaissance to Enlightenment: The Renaissance brought a resurgence of interest in medical knowledge, with physicians becoming more professionalized. Wealthy families still had personal physicians, but the general population began to access more standardized medical care through hospitals and clinics.

18th and 19th Centuries: The 18th century saw the emergence of the modern concept of a general practitioner. Physicians began to offer services to a broader population, not just the wealthy. The Industrial Revolution and urbanization further shaped medical practice, leading to the establishment of more formal healthcare systems.

Still, until the last 100 years or so, the idea of a personal physician was the domain of Kings and not many other people on the planet. The notion of every single person having a personal doctor is very new, and the details of how any society could afford that are still getting worked out.

Personal Physicians in Canada

Early Canada: In the early days of Canada, medical care was largely informal and provided by family members, midwives, and itinerant doctors. As communities grew, so did the demand for more structured medical care.

19th Century: By the 19th century, Canada saw the establishment of more formal medical practices. Physicians often served as general practitioners for entire communities, providing a wide range of services. The concept of a personal family doctor became more common, particularly in rural areas.

20th Century: The early 20th century witnessed the growth of medical institutions and the development of public health policies. The introduction of health insurance plans in various provinces, starting with Saskatchewan in 1947, paved the way for a more organized healthcare system.

Medicare: The most significant change came in the 1960s with the establishment of Medicare. In 1966, the Medical Care Act was passed, ensuring that all Canadians had access to essential medical services funded by taxes. This system fundamentally altered the relationship between patients and physicians, making personal physicians accessible to everyone, not just the affluent.

Modern Era: Today, personal physicians, often known as family doctors or primary care physicians, are integral to the Canadian healthcare system. They serve as the first point of contact for patients and coordinate their care, referring them to specialists when necessary. The system emphasizes continuity of care and the importance of having a long-term relationship between patients and their physicians.

The role and work of a family doctor in Canada have evolved significantly over the past century due to advancements in medical knowledge, changes in healthcare policy, and shifts in societal needs.

The New Plan

The current government in Nova Scotia was elected largely on the issue of Health Care and the Family Doctor issue and in the coming years may be judged a success or failure almost totally based on this one number.

First the bad news - this new number, 160,000 without a family doctor, is probably low. Not everyone who is without a doctor is looking for one or registered on this site.

Worse News:

· The population is increasing faster than the increase in graduating doctors and not all doctors and nurses stay in NS

· More doctors are retiring than before

· More people are in more need of doctors than before

· More people want more from their doctors and are getting less

To understand if 16.2% (and climbing) is a big number we have to ask questions to help us understand the context and our expectations of the number. Only then can we consider if this single number is a reasonable proxy for the state of our healthcare system.

What would we expect this number to be? For example, Full Employment does not mean there are no workers available. We expect some room to move as people change jobs, enter, and exit the workforce, move and otherwise come and go. With the latest surprise boost in Canadian employment statistics, our nation's unemployment level fell to just six percent. That's a number most economists consider to be Canada's full employment line. When we hit six percent, that's when our workforce is, for all practicable purposes, fully engaged.

The expected number is somewhere between zero people without a doctor, which is unachievable, and the number in countries with the best healthcare in the world.

NOTE: A complicating factor is that the increase, in fact nearly the total number of people without doctors, can be more than accounted for by the rapid increase in population over the last five years, which far outstrips the steady increase in the number of doctors. No element of infrastructure or production growth has come close to matching population growth due to immigration, therefore, though we’ve had record breaking growth as measured by population and GDP (Gross Domestic Production), our GDP per person, and prosperity however it is measured per person, has actually gone down substantially from where it was ten years ago.

I feel I should only note this here and write it out, with the math, more completely in another post.

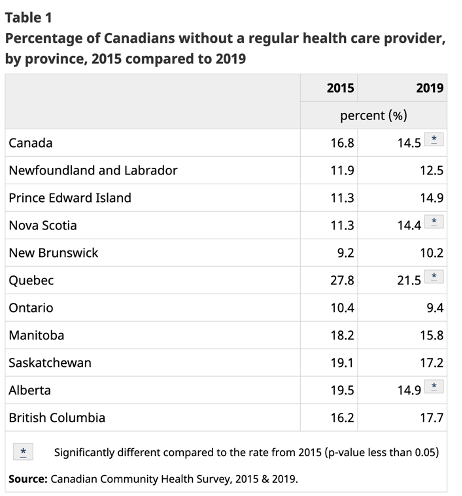

What is the percentage number of people without family medical care in other provinces?

The Canadian average is 14.5 percent. Provincially Quebec at 21.5% and BC at 17.2% have the highest but paradoxically healthcare outcomes in those provinces tend to be better than Nova Scotia.

What is the percentage number of people without family primary care in other comparable countries?

Internationally the figure on doctors is reported as the number of doctors per thousand people, which is considered a more factual basis for decision-making. The average for 2020 based on 26 developed countries was 3.53 doctors per 1,000 people. The highest value was in Austria: 5.35 doctors per 1,000 people and the lowest value was in Brazil: 2.05 doctors per 1,000 people.

If Nova Scotia were a country, it would be just outside the top ten position for most doctors in the world per thousand people.

Historically, what has the percentage number of people without family care been in the past in Nova Scotia and how has it changed over time?

Today Nova Scotia has more doctors per thousand people than it has ever had before.

Comparison Over Time:

100 Years Ago: Likely fewer than 1 family doctor per 1,000 people, with many areas relying on itinerant or part-time practitioners.

50 Years Ago: With the establishment of Medicare, the ratio improved significantly, perhaps reaching around 1-2 family doctors per 1,000 people.

25 Years Ago: Continued growth in the number of family doctors, approaching closer to the current ratio of about 2-2.5 per 1,000 people.

What do independent experts recommend as the right number?

The World Health Organization recommends that 2.5 doctors per thousand people are needed to ensure good health care. Nova Scotia presently has 3.42 doctors per thousand people.

What is the number in countries, provinces, and states, with the best healthcare result and how is it measured?

Spain is often considered to be the western country with the best healthcare system. Notably, in Spain doctors still regularly make house calls! Spain has 4.58 doctors per thousand people. Nova Scotia would need about 1,000 more doctors to reach that level.

Is this the best way to measure the thing we're concerned about? How would that best be described?

No. The thing we’re concerned with is good health. That’s not measured at all. The thing we are talking about is the sickness, aging, and injury care system and its success is not measured in the number of doctors, its success should be measured in results.

Is the current number changing in a meaningful direction? Is the underlying need changing?

Yes, the number is moving toward the actual number of people who don’t have a primary care provider, which is higher than reported. The underlying need is actually going down as people are living healthier longer than ever before. However, the demand for doctor services, the expectation of more and better care is rising at a rapid rate.

Is adding more doctors the best way to meet that need changing?

Doctors, along with nurses and a growing army of care workers are the frontline soldiers in the battle for our health. Their work, when accomplished in an effective and timely way, defines our healthcare system and how we look after the most vulnerable among us.

In summary, the current focus on the self-reporting of people without a primary care provider is probably understated, covers over other important issues, does not provide a good indicator of our health or the health of our system, and distracts us from our real goal – great health for all.

The role of family doctors has shifted from generalists providing a broad range of services to primary care providers focusing on preventive care, chronic disease management, and coordinated care within an interdisciplinary team. The number of family doctors per capita has generally increased over the past century, with variations influenced by policy changes, population growth, and evolving healthcare needs.

BUT… The reason for this mess of math is that numbers discombobulate the public as much as they do the media that will try anything to avoid them – and for good reason – people are bad at math.

So, we do need a way to speak to a fearful public transfixed by this one big number.

If We Really Wanted Change…

Nova Scotia has more family doctors than ever and the number is rising all the time. Why is it so hard to see them? Why are so many people still without doctors? How are few doctors taking on many more patients and seeing more of them each year in Ontario?

The answer is, that they, the Doctors, are highly motivated and incentivized.

And we can motivate Doctors too. Quickly and easily. If we choose. And we are at a position on the curve to change that percentage of people without a doctor number more and more quickly than any other province.

Here’s how we do it.

We Learn From Ontario’s Experiment in Family Care Payment Models.

Recently the Globe and Mail reported on a typical Family Care Patient in Ontario.

Allan Carpenter shuffles into the doctor’s office and gets down to business.

The 65-year-old patient and his long-time physician, Dr. Gordon, have plenty to talk about, even though they see each other for a check-up every second week.

Mr. Carpenter’s back and hip are so sore he worries he’ll end up in a wheelchair. He is anxious about getting to all his medical appointments, including a coming visit with an orthopedic specialist. He’s had HIV since the late 1980s, and he recently beat throat cancer.

“We do have a team of people that are trying to help you,” Dr. Gordon says, soothing his patient’s nerves, “and I know how much you’ve gotten out of it. But I know some days it’s difficult for you to get to these appointments. I get it. I hear you.”

For Nova Scotians without a family doctor, the thought of having a physician guide – a “captain of my ship,” as Mr. Carpenter calls Dr. George – is appealing in itself. But Mr. Carpenter is fortunate to have more than a captain. He has a whole crew.

His clinic east of downtown Toronto is part of the St. Michael’s Hospital Academic Family Health Team, a five-site organization with more than 200 staff, including nurses, dietitians, pharmacists and social workers, as well as clerical staff to support about 80 doctors and 36 medical residents.

This model, which Ontario calls the Family Health Team, is widely considered by health-system experts to be the best way to deliver primary care in the world, especially for patients like Mr. Carpenter with multiple complex medical conditions. Family doctors also favour the team approach because it helps them stave off burnout by sharing the workload. The Canadian Medical Association has named “expanding team-based care” as one of its top recommendations for solving the country’s health care crisis.

Ontario’s signature primary-care reforms offers lessons for other provinces departing from the old paradigm of lone doctors working fee-for-service in offices they own or rent themselves. British Columbia just announced a new approach to paying family doctors, and Alberta expects a new agreement reached with doctors in September will lead to more family physicians joining a model that includes paying physicians in team-based clinics to enroll patients for more continuity of care.

Ontario began overhauling its primary care system in the early 2000s. The new models paid family doctors working in groups mostly for the number of patients they enrolled in their practice, a departure from the traditional fee-for-service approach where doctors are paid for every discrete episode of care they deliver.

The alternative models blended capitation payments – which are annual payments to doctors for every patient on their roster – and fee-for-service to different degrees. The approach was supposed to encourage long-term relationships with patients and give physicians time to deliver comprehensive care to older, sicker patients who might have four or five health concerns to discuss at a single visit.

Currently there are 181 family health teams in Ontario.

The reforms succeeded. Doctors flocked to the new patient enrolment models, leading to a 43-per-cent increase between 2006-07 and 2015-16 in the number of Ontarians who said they had a family doctor.

Just to clarify that math expression as it might relate to Nova Scotia’s experience here’s some more math:

Currently, 83.8% of Nova Scotians are NOT reporting that the need a family physician. That’s the plus side of our current list where 160,000, 16.2% of Nova Scotians, are on a list reporting they are looking for a family doctor.

If we added new patient enrollments by even one-tenth of what Ontario achieved with their reform program, increasing the number of Nova Scotians who say they have a family doctor by 4.3%, we would have – by a wide margin – the lowest number of people seeking family doctors, not just in Canada, but anywhere in the world.

Would that get us the healthiest population in the world? Would it get us the fewest accidents or the least disease? Would it stop people from smoking, drinking, and eating until it made them sick?

Nope.

It wouldn’t do any of those things.

But it would at least shake us off our misplaced obsession with the number of doctors in Nova Scotia.

Let’s Talk About This.