When Voters Want Their Mom... and 8 other Weird Political Relationships

You promised! You never listen to me! You said you'd fix it! This isn't the present I wanted! You don't understand! You're not trying! I hate you!

A lot of popular music is filled with singers who are mad at their Dad but few hit the note more poignantly than Bowling for Soup. “Somebody Get My Mom” nails that feeling we’ve all had at some point—when life doesn’t go our way, and all we want is for Mom to come fix it. It’s that perfect blend of bratty frustration and dependency that doesn’t go away just because we’ve grown up. I laugh at seeing my sad self in this song every time because I’ve been there… like in the last week. In fact, if you listen closely, you can hear the same cry in lots of political conversations today. Whether it’s healthcare, housing, or taxes, the electorate treats leaders like they’re responsible for fixing everything right now—without ever acknowledging the complexities behind the scenes. Like the kids we once were, we want someone to swoop in, make things better, and reassure us that everything’s under control. But politics isn’t as simple as getting Mom to solve your problems—and maybe that’s why the tantrums keep getting louder.

Wait, Why Do I Even Care About This? A Guide to Political Self-Reflection

It got me thinking of the whole spectrum of weird political relationships, how they change, and how, like children, we get caught up in the fusing and fighting without thinking much about our thoughts or sharing our feelings about our feelings.

Metacognition is essentially “thinking about thinking.” I’m gonna use this tool to lay out the whole spectrum of political relationships. It involves awareness and understanding of one’s own thought processes. A metacognitive approach in any context is a way of engaging in critical self-reflection about how we perceive, process, and act on information. When applied to political discussions—or any complex decision-making—it means not just focusing on the content of a debate but also understanding the mental frameworks, biases, and cognitive steps that guide our own thinking as well as others’ thinking.

Thinking About Why We Think Politicians Suck

In the context of political discourse, a metacognitive approach involves stepping back from the heated issues themselves and considering:

How we arrive at our political positions.

Why certain types of arguments resonate with us and others do not - and how it changes over time.

What mental models or archetypes we use to categorize leaders, policies, and even opponents.

For example, understanding that a person may gravitate toward a "Visionary" leader because they are in a hopeful, idealistic mindset forces us to reflect on why others may not. It also helps explain shifts in political support—if someone previously supported a Visionary but now seeks a Father figure (I’m looking at you Canadian federal voters 2024), perhaps their personal needs or fears have shifted. When we recognize this change in ourselves and others, we understand that political leanings are often shaped by personal circumstances, cultural moments, and emotional needs.

This approach goes beyond simply arguing "right vs. wrong" or "good vs. bad" and invites us to think about why we’re drawn to certain positions and what mental shortcuts we might be using. When both sides of a debate are aware of their own cognitive processes, then maybe the discussion becomes more reflective, less reactionary, and more rooted in mutual understanding.

And maybe… it’s not them, it’s us.

Throwing a Tantrum: Voters, Politicians, and the Parent-Child Complex

By framing each leadership archetype with its corresponding electorate mood, we might capture the dynamic relationship between leaders and the people they serve. The more a leader embodies an archetype, the more they inspire specific behaviors, emotions, and attitudes in both supporters and opposition. The shifts reflect the electorate’s changing desires for hope, security, or even rebellion based on the cultural or economic moment.

“If what I say now seems to be very reasonable, then I will have failed completely. Only if what I tell you appears absolutely unreasonable have we any chance of visualizing the future as it really will happen.” Arthur C. Clarke

In January 1842 Charles Dickens's ship was waylayed in Halifax en route to New York. He observed of the place…

“I suppose this Halifax would have appeared an Elysium, though it had been a curiosity of ugly dullness. But I carried away with me a most pleasant impression of the town and its inhabitants and have preserved it to this hour.

It happened to be the opening of the Legislative Council and General Assembly, at which ceremonial the forms observed on the commencement of a new Session of Parliament in England were so closely copied, and so gravely presented on a small scale, that it was like looking at West- minster through the wrong end of a telescope. The governor, as her Majesty's representative, delivered what may be called the Speech from the Throne. He said what he had to say manfully and well. The military band outside the building struck up " God save the Queen " with great vigour before his Excellency had quite finished; the people shouted: the in's rubbed their hands; the out's shook their heads; the Government party said there never was such a good speech ; the Opposition declared there never was such a bad one ; the Speaker and members of the House of Assembly withdrew from the bar to say a great deal among themselves and do a little; and, in short, everything went on, and promised to go on, just as it does at home upon the like occasions.”

1. The Visionary (The Idealist / The Savior)

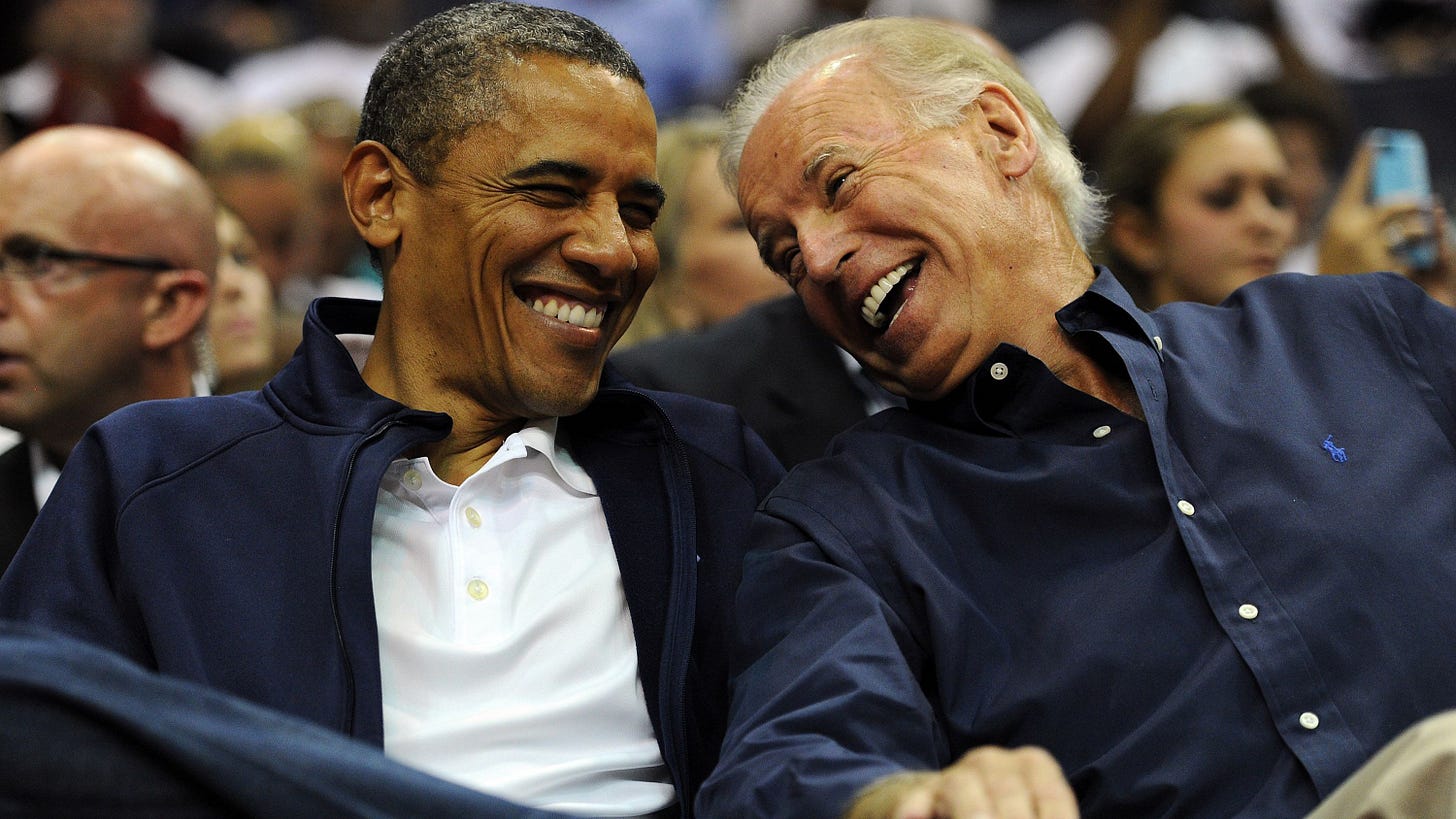

Examples: Justin Trudeau (early years), Barack Obama, Emmanuel Macron (initial run)

Key Traits: Focus on hope, optimism, and the promise of a better future. They sell a big idea, a better world just around the corner. Often associated with youth, change, and progressive policies.

Appeal: Emotional connection, inspiring belief in something bigger. These leaders are elected during times of discontent or stagnation, offering a fresh start.

Risks: If they fail to deliver or don’t deliver quickly enough, voters may feel disillusioned. They often struggle when practical, grounded leadership is required.

Electorate in Support: They are happy, hopeful, and optimistic. The electorate believes in a brighter future, enjoys seeing their leader in relatable, almost personal ways—whether with family or engaging in lighthearted public events. They’re inspired, patient, and willing to overlook mistakes as long as the vision remains intact. They feel part of a collective mission and take pride in their leader’s charisma.

Electorate in Opposition: Frustrated, cynical, and sour. They see the Visionary’s grand ideas as impractical or naïve. They accuse the leader of focusing too much on appearances and symbolism rather than getting things done. They might feel left out of the "feel-good" narrative, especially if their personal issues seem ignored by the broad, sweeping vision.

2. The Father/Mother (The Caregiver / The Manager)

Examples: Joe Biden, Angela Merkel, Brian Mulrooney

Key Traits: Protective, pragmatic, a steady hand. They focus on stability, safety, and caretaking. Often elected after a period of upheaval or crisis, when people want someone to bring things back under control.

Appeal: Reliability, competence, and calm. They are chosen to solve problems in the here and now and often avoid dramatic ideological shifts.

Risks: Seen as uninspiring or slow to act, especially during crises demanding bold vision. No fun.

Electorate in Support: Reassured, comforted, and trusting. They want someone to fix things and be a steady hand in turbulent times. They expect their leader to solve problems like a dependable parent—balancing budgets, restoring normalcy, and fixing societal issues. They appreciate experience and competency over charm or big promises.

Electorate in Opposition: Childish, impatient, and critical. They get angry that Dad isn’t solving their problem fast enough. They complain about broken promises and unmet expectations, often overlooking how complicated issues really are. They demand quick fixes and personalized attention, throwing accusations like “He said he’d fix this, and it’s still broken!” Their discontent often sounds petulant, like a child frustrated with an overly busy parent.

3. The Patriarch (The Authority Figure / The Strong Leader)

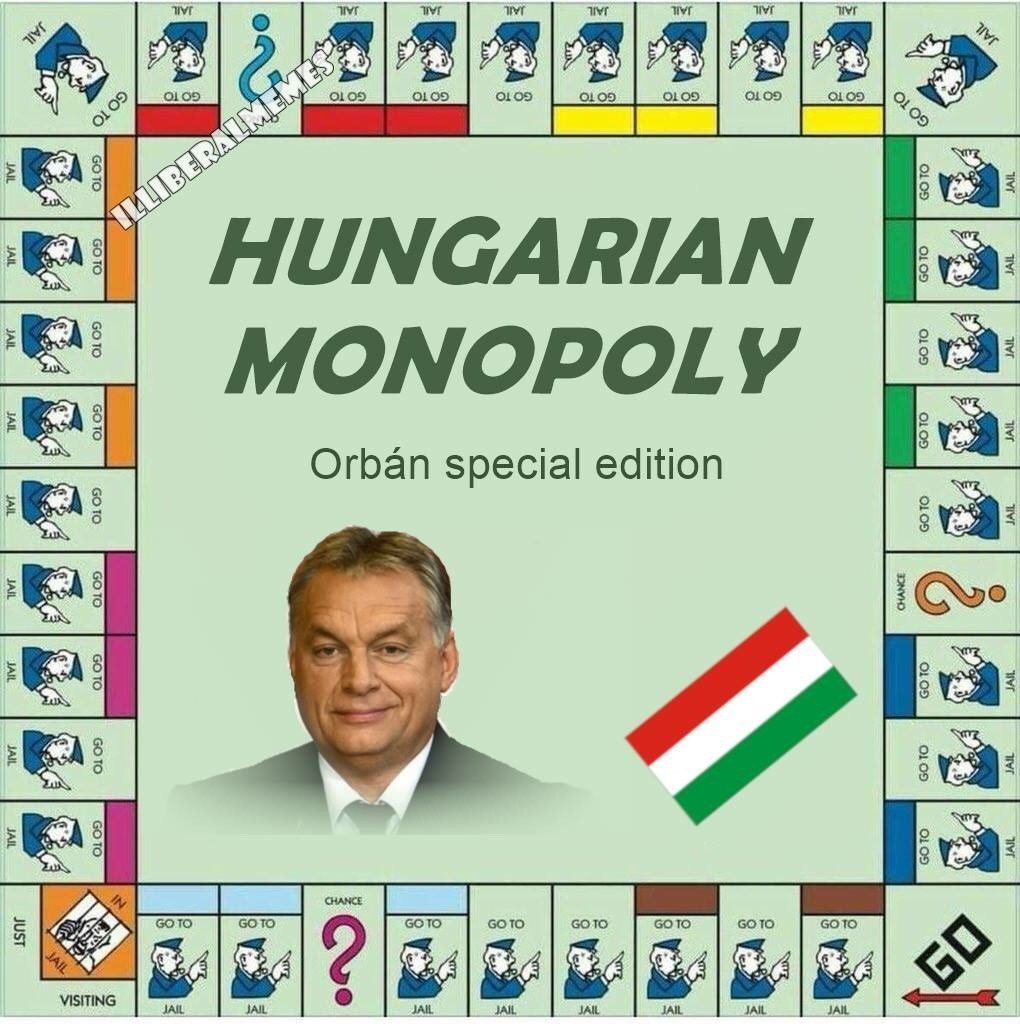

Examples: Donald Trump, Viktor Orbán, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

Key Traits: Strength, order, discipline. They present themselves as tough protectors who will do what needs to be done, no matter how unpopular. They thrive on chaos or the perception of an enemy or existential threat.

Appeal: A sense of control and order, especially in times of fear, economic distress, or cultural anxiety. They project power and are willing to 'get things done' even at the expense of norms or civility.

Risks: Polarizing. Often provoke as much animosity as they do devotion, leading to political instability or authoritarian drift.

Electorate in Support: Obedient, protective, and loyal. They rally behind the leader’s strength, valuing order, discipline, and clarity. In moments of crisis or social turmoil, this electorate feels safer under a decisive, uncompromising leader. They’re willing to overlook or even applaud actions that challenge democratic norms if they believe the leader is defending their values or the nation’s security.

Electorate in Opposition: Defiant, fearful, and suspicious. They see the strong leader as overbearing, authoritarian, or dangerous. They may feel persecuted or powerless, fearful that their rights or freedoms are under threat. Opposition is often framed in moral or ethical terms—accusing the leader of bullying, trampling on norms, or suppressing dissent.

4. The Commander (The Warrior / The Crisis Manager)

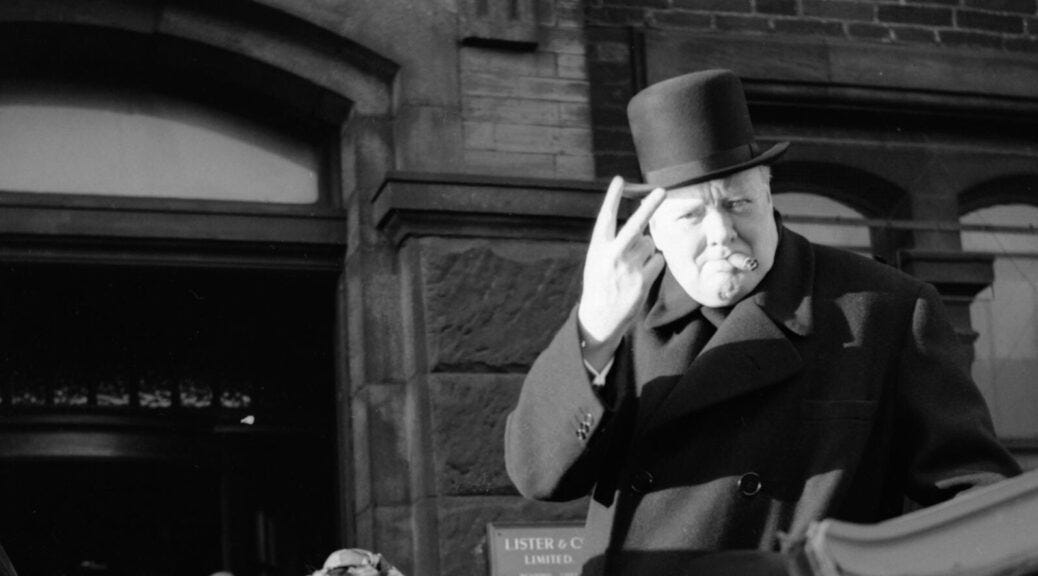

Examples: Winston Churchill, Margaret Thatcher, Rudy Giuliani (post-9/11)

Key Traits: Leadership in times of war or crisis. They thrive on clear and present danger, offering decisive action, strong rhetoric, and an “us vs. them” mentality.

Appeal: They are called upon when voters seek someone willing to fight on their behalf. They take risks and make tough decisions.

Risks: Struggle in peacetime or post-crisis situations, where their confrontational style can feel heavy-handed or out of place. It’s always astonished me that Churchill lost the first post-war election.

Electorate in Support: Energized, combative, and proud. This electorate is motivated by a sense of collective danger, whether real or perceived. They appreciate the commander’s no-nonsense, action-oriented leadership, especially during war, economic collapse, or natural disasters. They admire the leader’s toughness, framing the political battle as a fight for survival.

Electorate in Opposition: War-weary, critical, and anxious. They become skeptical of the endless conflict, viewing the leader as too focused on the fight rather than the aftermath. They begin to ask, “When will it end?” and resent the ongoing stress. Some may start questioning whether the crisis is exaggerated for political gain, feeling fatigued by perpetual emergency mode.

5. The Technocrat (The Problem-Solver / The Bureaucrat)

Examples: Stephen Harper, Angela Merkel, Mario Monti (Italy)

Key Traits: Policy wonk, data-driven, rational. These leaders are often seen as the ‘best choice’ in times of complex problems like economic downturns, recessions, or pandemics. They emphasize technocratic solutions over ideology.

Appeal: Competence and expertise, offering practical solutions rather than grand visions. They appeal to moderate or disillusioned voters who just want things to work.

Risks: Can be seen as uninspiring or disconnected from the human, emotional elements of leadership. Often struggle to communicate or inspire during moments of national identity or cultural crisis.

Electorate in Support: Rational, pragmatic, and calm. They’re not looking for inspiration or grandiose promises—they just want competence. They appreciate a data-driven approach, valuing steady progress over flashy rhetoric. This electorate likes that things are getting done efficiently, even if the changes are incremental or unseen.

Electorate in Opposition: Disillusioned, bored, and disengaged. They see the technocrat as a soulless manager, disconnected from the human elements of leadership. They may accuse the leader of being out of touch, cold, or lacking vision. This electorate often feels like the leader is focused on process over people, leading them to disengage or vote for more emotionally charged alternatives.

6. The Populist (The Outsider / The Maverick)

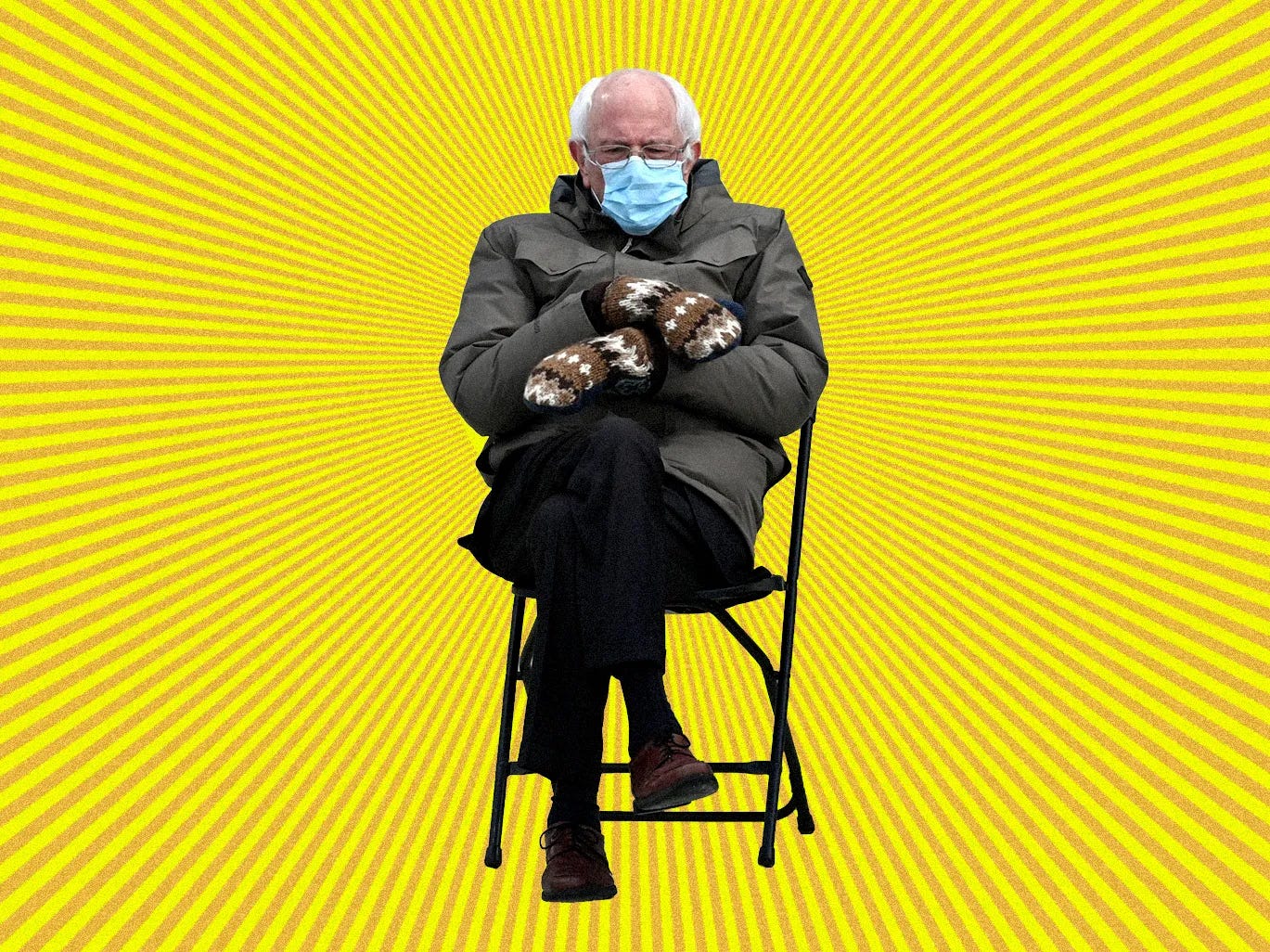

Examples: Bernie Sanders, Marine Le Pen, Jack Layton, Rob Ford

Key Traits: Anti-establishment, anti-elite, often from, or perceived, outside traditional power structures. They pitch themselves as champions of the common people, railing against corruption or the failures of the status quo.

Appeal: Direct, plain-speaking, and often radical. Populists give a voice to people who feel left out of the current system, especially during periods of growing inequality or disillusionment with elites.

Risks: Can struggle to govern effectively, as they often lack the experience or institutional support needed to navigate complex systems. Risk of destabilizing institutions.

Electorate in Support: Angry, rebellious, and fed up. They feel ignored, left behind, or betrayed by traditional elites, and they see the populist as their champion. They’re motivated by a desire to shake up the system, punish corrupt elites, and restore power to the "common man." This electorate thrives on disruption, and they cheer on the leader’s unconventional style, even if it’s chaotic or polarizing.

Electorate in Opposition: Scornful, anxious, and fearful. They see the populist as reckless, destructive, or manipulative. They fear the chaos, the undoing of norms, and the possible damage to institutions. This electorate accuses the leader of being divisive, unqualified, or pandering to baser instincts.

7. The Revolutionary (The Radical / The Change Agent)

Examples: Che Guevara, Thomas Sankara, Hugo Chávez (early years)

Key Traits: Radical overhaul, rejecting existing systems. These leaders call for systemic change, often from a socialist or leftist standpoint. They promise a break from traditional forms of governance and appeal to voters deeply disenchanted with the system.

Appeal: Sweeping change, revolution, and often the promise of equality and justice. These leaders are attractive to those who feel deeply disenfranchised by political and economic systems.

Risks: They often push too far, too fast, leading to instability, authoritarianism, or economic failure.

Electorate in Support: Passionate, idealistic, and radicalized. They’re deeply dissatisfied with the status quo and believe the system is beyond reform. They’re energized by the promise of sweeping change, social justice, and overthrowing entrenched power structures. This electorate is often younger, more diverse, and demands urgent action, willing to take risks for the sake of equity and fairness.

Electorate in Opposition: Terrified, conservative, and reactionary. They see the revolutionary as a threat to stability, property, and tradition. They fear the loss of personal freedoms, economic security, or cultural values. This electorate pushes back hard, framing the revolutionary as reckless or even dangerous to the nation’s fabric.

8. The Populist-Authoritarian (The Strongman / The Autocrat)

Examples: Vladimir Putin, Jair Bolsonaro, Rodrigo Duterte

Key Traits: Blends populism with authoritarianism. They exploit crises, economic turmoil, or cultural divisions to consolidate power. They are anti-establishment yet operate within the system to gain and maintain control, often undermining democratic norms.

Appeal: Strong leadership combined with a ‘man of the people’ persona. They promise swift justice, often with little regard for rule of law or human rights.

Risks: Long-term erosion of democratic institutions, rise of political violence, and polarization of society.

Electorate in Support: Fervent, loyal, and uncritical. They rally behind the leader’s strongman image, valuing order and the decisive crush of opposition. They feel represented by someone who isn’t afraid to bend the rules and put “outsiders” in their place. This electorate is often fueled by nationalism, fear of decline, and a desire for law and order. They’ll justify nearly any action the leader takes because they believe it’s necessary for the greater good.

Electorate in Opposition: Resistant, fearful, and sometimes exiled. They see the leader as a direct threat to democracy, individual freedoms, and minority rights. This electorate often feels persecuted, seeing themselves as part of the resistance, either literally or figuratively. They may also view themselves as defending the very soul of the nation from an authoritarian takeover.

9. The Philosopher King (The Sage / The Wise Leader)

Examples: Nelson Mandela, Vaclav Havel, Aung San Suu Kyi (pre-controversy)

Key Traits: Morally upright, transcendent, and often spiritual. These leaders combine wisdom, ethical guidance, and a deep moral conviction, rising above political squabbles to inspire a sense of purpose and higher ideals.

Appeal: Inspirational, guiding their nation through deeply transformational moments. They often lead after periods of immense conflict or injustice.

Risks: Can become isolated from realpolitik, or be used as figureheads without real power. They sometimes struggle in more pragmatic or bureaucratic roles.

Electorate in Support: Inspired, reflective, and moralistic. They are drawn to the leader’s wisdom, moral authority, and ethical grounding. They want a leader who transcends petty politics and inspires the nation to think in higher terms—whether about justice, equality, or reconciliation. They are more patient and thoughtful, valuing long-term vision over short-term gains.

Electorate in Opposition: Dismissive, impatient, and practical. They see the leader as disconnected from reality, focusing on lofty ideals while ignoring the day-to-day problems people face. They accuse the leader of being out of touch or overly intellectual, wanting someone more grounded and pragmatic. They may even mock the leader’s high-mindedness as impractical or elitist.