What's Wrong With Canada? It Depends on Who You Ask.

Top 10 Lists count down what's wrong with Canada from different Canadian perspectives and define our difficult DEADLOCK DIAGRAM where... well, something has gotta give around here.

A deep dive into Canada’s competing crises—housing, immigration, Indigenous policy, bureaucracy, and national identity—through the eyes of four different groups. This essay maps where Canadians agree, where they collide, and what it means for the future of the country.

Plus a lot about wrenches, humanism, pop music and songs you might have missed, the dead as a voting bloc, and the flammability of flags.

All in this summer week end edition of THE BEE

For this Essay, I’ve read and listened as carefully as I can to four constituencies in Canada and sorted their Top Ten lists of What’s Wrong With Canada.

Then I made a grid and tried to find the issues and framing that they mostly agree on.

Can we start here?

Then we’ll all look together at the Deadlock Diagram, a summary analysis of where our ideas about what’s wrong with Canada directly conflict.

Let’s see how that goes…

When I was a kid, my Pictou County grandfathers, both coal miners whose bodies had come to the end much sooner than they did, never had the right tool for the job.

One thing that was a constant was taking the one old open end wrench they had and, because it was always the wrong size, using a big wooden handled screw driver or a penny, or anything, pressed in the gap to make up the difference. This worked good enough on old square nuts but really made a mess of “modern” hex-shaped nuts. It also made my father nuts. He had worked hard to leave this Pictou County life behind when he joined the RCN, and he was an engineer officer, in fact, the head of the Fleet Repair Unit at the Dockyard. It was his job to make sure tools were used properly. The kindest thing I ever heard him say about these old men was that they were “hard on equipment”.

What they all had in common was a deep interest in figuring out the problem and fixing it. They all had a tremendous capacity for effort in this regard that was matched by an ability to improvise in the most difficult situations. This, I’ve come to believe, is the true mark of a man, and the heart of what masculinity is all about — the ability to stay in the situation, however uncomfortable, and improvise solutions. It probably doesn’t matter much in the good times, but when things go bad, these are the men you want around.

In today’s terms, this might be called creativity.

"The deepest joy in life is to be creative. To find an undeveloped situation, to see the possibilities, to decide upon a course of action, and then devote the whole of one's resources to carrying it out, even if it means battling against the stream of contemporary opinion, is a satisfaction in comparison with which superficial pleasures are trivial. But to create, you must care."

Adm. H. G. Rickover, USN

I think of these old timers often when people say this or that is what’s wrong with Canada.

Now, in fairness, you wouldn’t have to read much of THE BEE to guess what the algorithm feeds me all day long. I get to hear more than most people about what’s wrong with Canada. And because of my peculiar place in the field, I kind of hear it from all sides.

So I thought in this essay, I’d try to make a summary of a sample of the sides (there are many more I am sure) and see where the common ground was and what the deadlocked diagram of differences looked like when we’re talking about what’s wrong with Canada.

Maybe we don’t have the right tool for the job, and it’s certain that we’re hard on equipment. I don’t care as much as my father did about the difference between 5/8th’s and 9/16th’s, but maybe if we all just stand back and look at it the right way, creatively, we can figure out how to fix What’s Wrong With Canada.

I’m almost absurdly optimistic and see the whole long path of human history as a march toward each other and toward better times ahead. So this ‘What’s Wrong With Canada?’ list thing doesn’t come that easily to me. Still, it’s the currency of the age, and no matter how far we come, it’s the citizen’s job to imagine more and better, and to have the courage to speak out and ask for it, for us, and for the rising generations to come.

So, what do young Canadians think is wrong with Canada?

In the words of the great British philosopher-poet Harry Styles, “It’s not the same as it was.”

Young Canadians aren’t angry the way older generations are. They’re tired. Disenchanted. Swallowed by systems they didn’t build, can’t fix, and have no choice but to navigate. Their rebellion is quieter: opting out, starting side hustles, staying single, not voting, or moving away.

This list doesn’t rage. It sighs.

And beneath it all is one haunting question:

“What if this is as good as it gets?”

At the exact moment when these kids should be most free to explore, live, love, think great thoughts, and have babies in joyful households made to help, we’ve worried them half to death, burdened them with crushing debt, and offered them no prospects of better times to come or given them any sort of real instruction or true education on how to live.

In previous eras—whether in churches, immigrant families, rural towns, or even mid-century suburbs—young people were handed a kind of moral scaffolding. It could be narrow or rigid, sure, but it was there: you work hard, start a family, stay close to home, contribute to community, serve your country, obey your elders, and trust in something bigger than yourself. Life was a path, not a puzzle.

By the 1970s, that guidance began to soften under the weight of social revolutions, economic change, and a growing faith in individualism. Parents—perhaps still recovering from the burden of too much direction in a post-war world—swung hard the other way: "Follow your heart." "Be yourself." "Do what makes you happy." It was well-meaning, but dangerously vague. It replaced duty with desire and mistook freedom for fulfillment. The implicit message? You're on your own, kid.

Fast-forward to today, and the guidance has thinned even further—if it exists at all. Many in Gen Z (and the younger half of Millennials before them) have grown up in households where therapy-speak and influencer wisdom have replaced grandma’s blunt advice (which in my family ranged from ‘do as you are told’ to ‘stop thinking so much’, which seemed absurd and aweful at the time but now… words from the wise are as goads) with “find your truth,” “set boundaries,” and “you owe no one anything.”

So, where is guidance coming from today? Young people rely heavily on one another—online and off—for moral and emotional calibration. But peers have no more wisdom than they do. It’s the blind leading the confused. TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram now function like secular scripture: offering life advice, moral judgments, political identities, and self-help clichés in bite-size dopamine hits. In Therapy Culture mental health language has replaced moral language. Words like trauma, self-care, boundaries, gaslighting, and “toxic” dominate discourse. This can be helpful—but also deeply self-referential.

Universities, HR departments, and activist organizations have stepped into the vacuum with their own moral frameworks. These are often ideological, jargon-heavy, and rooted in grievance and group identity rather than personal virtue, household bonds, or shared citizenship.

The result? Many young people feel free but unformed. Liberated but lost. Empowered but anxious. And more than anything—alone.

The paradox of modern freedom is that without some structure, it's indistinguishable from abandonment. The challenge ahead is to rebuild guidance that doesn't feel like control—and identity that doesn't demand ideology. The need is not for more choices, but better maps.

Here’s a top ten list of What’s Wrong With Canada, as most often reported by the young folks.

I’m including this Harry Styles song because, as many times as you’ve heard it over the past three years, you’ve probably never really listened to the lyrics. They are profoundly and persistently hopeless, meaning absent of hope for even escaping the gravity of the moment, let alone imagining a better future.

A Convoy of Conservatism

Polievre or not, Canada has its own brand of people who somehow imagine that they night be better off, more respected, be treated better, and have more fun as some sort of high-level soldier in a post-apocalyptic militia than in Canada today. At the extreme, we might call this the ‘Burn it all f#&kin’ Down’ crowd. But the thing about these folks, like their MAGA cousins, is that they are mostly the good and decent people, the salt of the earth, the people most likely by far to show up and help without hesitation if ever anybody needed help. They are the ones you see running toward the burning building, car accident, or basically anyone who needs help. They’re the ones donating and giving more than most.

So when they say this is how they feel, this is their perception of the astonishingly complex situation that is Canada, I just can’t see any reason to not sit down with them and try to understand why this might be their top ten list of what’s wrong with Canada without imagining that the Right is really that far from the good and the right.

OK, I’ve used some commonplace words here as shorthand. Let’s drop the populist, conservative, and other labels and just call this group Westy’s. Not necessarily because they’re from the West but because it represents an independent, frontier, ‘willing to go it alone’ spirit.

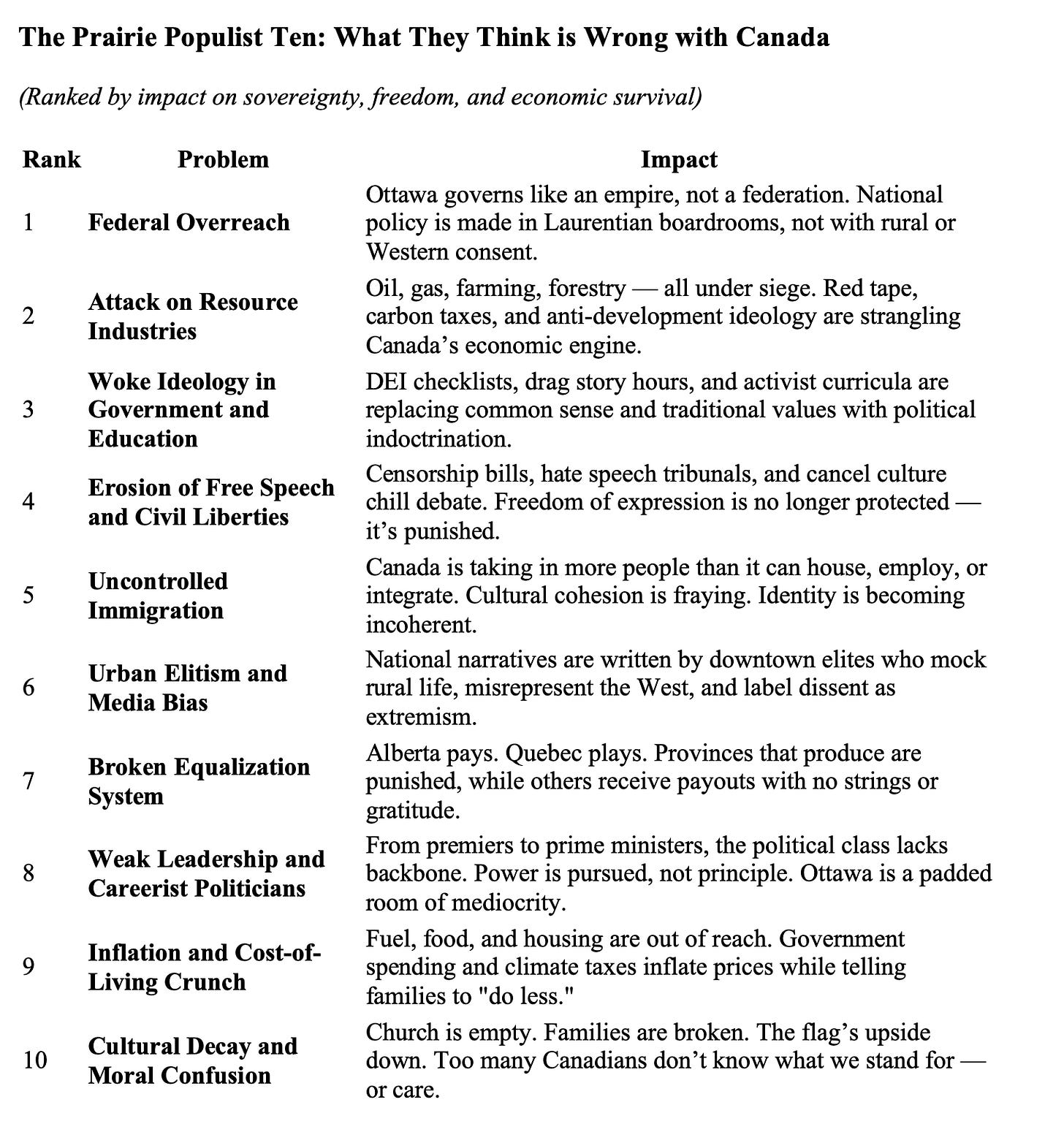

For this crowd — farmers, tradespeople, truckers, oil workers, ranchers, and their communities — this list isn’t a “take.”

It’s a diagnosis.

Not of what’s wrong in the news, but what’s wrong with Canada.

This list speaks not in theories or trends, but in perception, worry, and lived experience. It’s about sovereignty, family, work, and the fight to be heard in a country that — to them — feels like it’s being run for someone else, by someone else. It’s a concern that we’ve left too much of the past behind.

Humanism, at its classical core, is the belief that human beings—through reason, art, learning, empathy, and virtue—can live meaningful lives and build better societies. It emerged during the Renaissance as a response to the rigidity of medieval thought. But crucially, it didn’t reject the past—it reclaimed it.

Think Petrarch digging up Cicero’s letters. Think Erasmus editing the Bible with reverence for Greek. Humanism wasn’t anti-tradition; it was anti-dogma. It sought to recover the wisdom of the ancients, not discard it.

Like the Humanists that brought us classical liberalism and the Renaissance, Westy’s are pushing back against what they see as rigid dogma and a sympathetic determination that we not abandon too much of the past that we’ll need down the road.

Progress, Purpose, and Prosperity

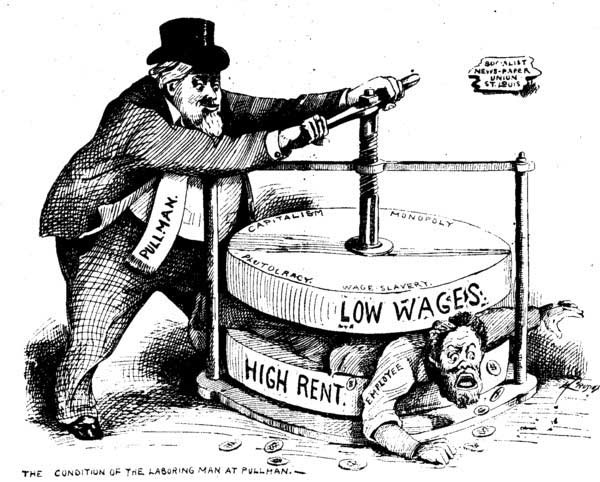

I consider myself a progressive. I'm deeply immersed in the values and ideas of the Progressive Era—that remarkable period in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when reformers, journalists, policy thinkers, and citizens set out to fix the excesses of industrial capitalism, tame monopolies, clean up government, and expand the promise of democracy. They believed, profoundly, that society could be improved. Not perfected—but improved—through effort, reason, and moral imagination.

That era still speaks to me. Its reformers weren’t revolutionaries. They weren’t trying to burn it all down. They wanted to clean up the machine, not smash it. They sought fairness, not utopia. And they often began by asking: what are we not seeing? who is being left behind? what can we do about it?

I can’t help but be deeply influenced by what feels like a new echo of the progressive era unfolding in our own time. There’s a similar impulse—to correct injustice, to widen inclusion, to hold power to account. There’s a hunger for transparency, for accountability, and for change.

But I’m also aware that today’s echo has a different frequency. The old progressives were builders. They prized civic institutions, open debate, and the messy work of incremental reform. They believed in citizenship as the shared identity. Today’s progressives, too often, lean toward purity over persuasion, identity over solidarity, and grievance over responsibility. There's energy—but also anger. There's clarity—but often at the cost of complexity.

Still, I can’t walk away from the project. I remain, by instinct and inheritance, a progressive. I want to believe that with the right combination of ideals and pragmatism, of memory and momentum, we can keep nudging the arc of history—not toward ideology, but toward dignity.

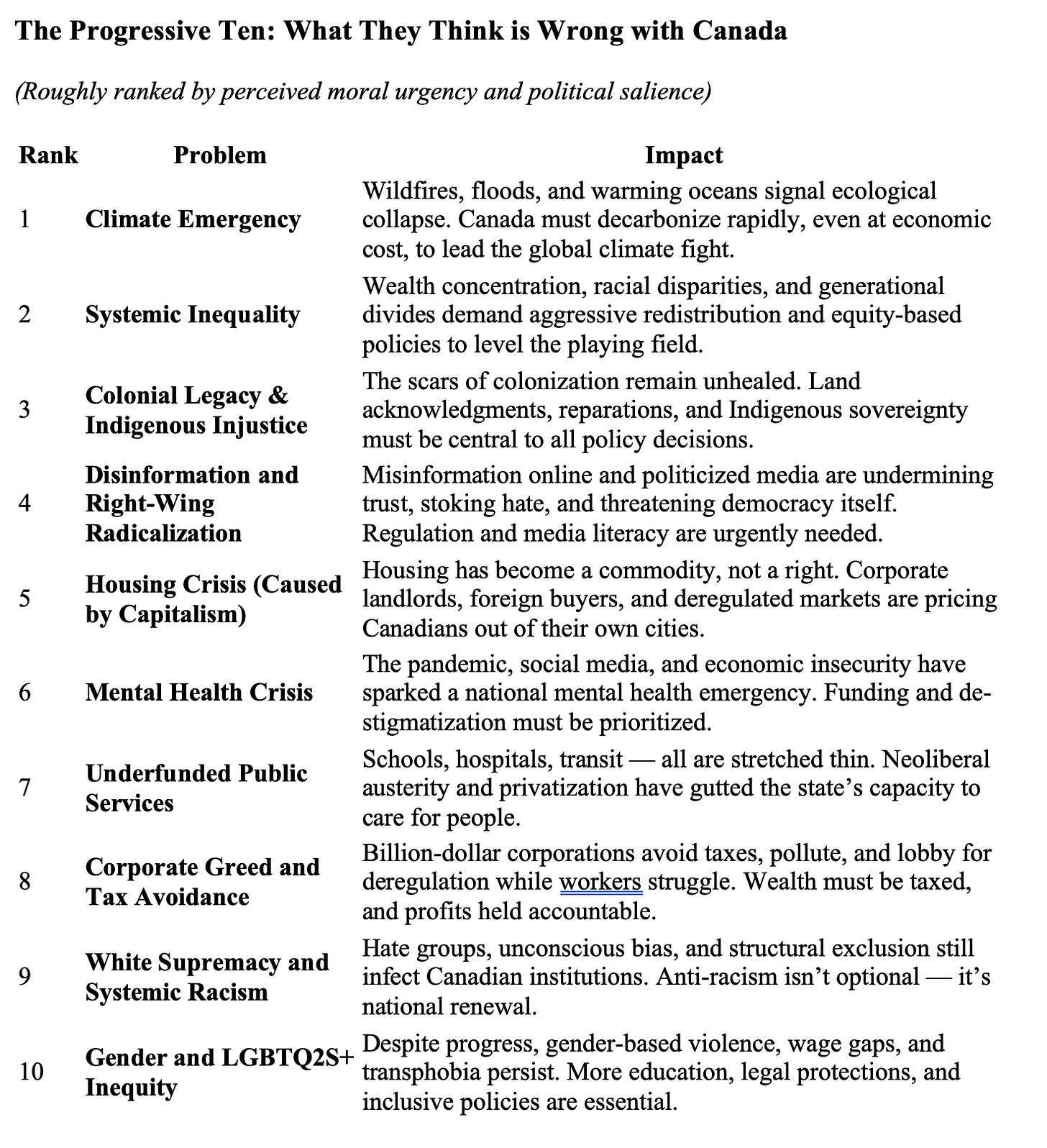

What’s today’s Progressive top 10 list of what’s wrong with Canada?

We all know and identify closely with this list. It’s in the media, the nightly news, the CBC, the universities, and the rest. Our awareness of this list is 5 x 5.

Democracy is run by the radical fringe because normal people have stuff to do

The phrase "silent majority" has a long and powerful history in politics and public discourse, often evoking the idea that a large group of people—typically average, non-vocal citizens—hold values or opinions that are ignored or dismissed by elite or activist voices.

Joan Didion called it “a convenient rhetorical device for saying what you want without having to prove it.”

Others argue the term is often used not to describe a real majority, but to claim one, implying moral or electoral superiority without evidence.

The silent majority" is a political spell. It's used to conjure a moral consensus that can't easily be polled, seen, or shouted down. Sometimes it's real. Sometimes it's wishful thinking. But it's always potent.

It’s potent because it describes something we all feel is out there.

I’m going to call this group, who are the least likely to speak up in media, government, and socials, but are felt nonetheless in the conversation, The Canadian Civic Realist, or CCR or Realists for short.

I’m just looking for some term for a group that, because of their tenor and tone, does not have a chosen or given label. And I’m trying to avoid ‘Silent Majority’, centrist, and other such titles. It would be classic politics, but a real heavy lift, to claim to speak for the silent majority.

But I also want to accept that they exist to some degree and have a certain wisdom. The silent majority doesn’t make noise; they make history.

Interestingly, the term originally referred to the dead—“the silent majority” as those who had passed on.

“Democracy means despair of finding any heroes to govern you, and contented putting up with the want of them. ... The voice of the people is as the voice of God... but it is well to remember that the people are mostly dead—the silent majority, we may say.”

—Scottish philosopher and essayist Thomas Carlyle, Sartor Resartus (1831–33)

So, I’ll make it a kind of tautology and define them by what they believe. They are not ideologically left or right — just grounded. Focused on productivity, equality, sustainability (real, not rhetorical), and national cohesion. A builder. A reformer. A nationalist with open eyes.

The realist can see the slavery sewn into the fabric of our clothes; chaos and commotion wherever they go. And they can see there’s no real reason things are this way. That most of humanity—past, present, and to come—does not march, nor trend, nor shout, but rather lives quietly, labours long, and leaves behind traces more lasting than applause.

Canada’s War of Problems:

Who’s Fighting What?

There’s something poignantly Canadian about watching protesters try to burn a Canadian flag made of fire-retardant polyester.

They wave lighters, fan the fabric, chant with conviction—and the thing just won’t catch. It’s not so much a protest as a childish tantrum with flame-resistant capitalism.

You can almost hear the flag say: “Sorry, I don’t do this kind of drama.”

In this next section, we’re going to take the various “What’s Wrong with Canada” lists we’ve created—each reflecting a different group’s perspective—and lay them side by side.

The goal has two parts:

To find common ground—issues that appear across multiple lists, even if phrased differently. These are shared concerns, places where meaningful consensus or cooperation might actually be possible.

To map the deadlocks—what we might call the zero-sum conflicts, where one group’s priority is seen as the root problem by another. These are the issues that make dialogue hard and progress harder. They’re not just differences of opinion; they represent opposing visions of what Canada is for and what kind of country we should be building.

Think of it like a conflict map—on one axis, the shared ground that offers opportunity; on the other, the contested ground where one group’s solution is another’s nightmare.

By laying this out plainly, we can see not just what’s broken, but why it’s so difficult to fix—and what kind of cultural or civic work might be needed to break the deadlock.

Areas of Overlap (Opportunity for Agreement)

Housing / Infrastructure

Everyone agrees we’re not building enough or fast enough.

Young people want affordability. Westy’s want market access. CCR’s want red tape gone.

Shared concern: Permitting reform, faster builds, less obstructionism.

Healthcare

Progressives and CCR’s see a crisis and just want to help people. Westy’s fear ballooning costs.

Shared concern: System unsustainable without reform.

Education Quality / Access

CCR’s highlight falling outcomes. Progressives want more inclusion and access. Young people want value for cost. Westy’s are tired of being put down by this system.

Shared concern: Education is failing. Needs fixing.

Government / Institutional Trust

Westy’s rail against overreach. Young people feel powerless. CCR’s see bureaucratic bloat. Westy’s see the enemy.

Shared concern: Distrust and inefficiency are rotting institutions.

Energy & Environment

CCR’s want engineering-based energy policy. Progressives want best green solutions. Young people want climate addressed without being priced out. Westy’s want to ‘drill baby drill’.

Shared concern: Canada needs to power itself — wisely and affordably.

So that’s the good news. But now the harder part. Canada’s gridlock isn’t just about disagreement; it’s about direct conflict between values and priorities across political and generational lines. Some problems appear to be zero-sum: you can’t solve one without aggravating the other.

Let’s break it down cleanly:

The DEADLOCK DIAGRAM

Mapping Canada’s Irreconcilable Problems

Direct Conflicts Between Top-Ten Priorities

So let’s sum it up.

Despite different language and blame targets, there is ‘intersectionality’; some core concerns echo across all four worldviews:

Things aren’t working.

Every group sees dysfunction — whether in government, healthcare, housing, or education. Canadians know the machine is grinding and sputtering. No one believes it’s firing on all cylinders anymore.

Economic anxiety is real.

From productivity collapse to housing unaffordability to inflation and job market chaos — everyone agrees that making a life in Canada is getting harder.

Institutions are losing trust.

Media, government, schools, courts, and even democracy itself — all are viewed with skepticism. Whether it’s “media capture” on the right or “corporate greed” on the left, or just quiet Gen Z disillusionment — the throughline is: no one’s steering the ship well.

A crisis of vision.

There’s a shared sense that Canada is drifting. We lack a national story that inspires, a direction that unites. Each list is a fragmented plea for clarity, for leadership, for something worth building together.

The Deadlock Diagram names Zero-Sum Differences (Where Compromise Seems Impossible)

Indigenous Governance vs. National Sovereignty

Some see Indigenous legal power as overdue justice. Others see it as legal gridlock. Equal treatment under the law vs. bloodline inheritance. This is a constitutional collision course — not just about land, but who gets to say what Canada is.

Climate Policy vs. Economic Survival

For progressives and youth, decarbonization is existential. For resource-based Canadians, it feels like economic suicide. There’s no obvious middle here — not without new technology or national sacrifice.

Immigration Policy

Progressives see it as a moral good and demographic necessity. Populists and pragmatists see it as destabilizing without housing, jobs, or unity. Youth are squeezed in between — told to compete in a rigged market made worse by rapid growth.

Culture and Values

One side wants more inclusivity, fluid identity, and diversity. The other wants tradition, roots, and shared norms. These are not minor disagreements — they’re about the soul of the country.

If the goal is a prosperous Canadian nation in a peaceful world, here’s what that demands — not of government, but of us, as citizens

So What Do We Do With This? What Must Citizens Do?

If the goal is a prosperous Canadian nation in a peaceful world, here’s what that demands — not of government, but of us, as citizens:

Relearn How to Argue

We need a civic culture that prizes listening without surrender, disagreement without dehumanization, and debate without cancellation. This means:

Platforms for honest discussion

Local forums and citizen assemblies

Teaching rhetoric and critical thinking in schools again

Rebuild the Concept of Contribution and Shared Responsibility

Every group wants something. But citizenship isn’t about wanting. It’s about contributing. To the future.

We must revive the idea that we are co-authors of this country, not consumers of it.

That means work, service, sacrifice — and yes, taxes — in pursuit of the common good.

Define a New Canadian Story

All four lists agree on one thing: something is missing. We need a new national myth — not fake, but aspirational — rooted in:

Creation (what we will make and build together)

Cultivation (what we steward, care for, protect)

Continuity (what we pass on — culture, institutions, land)

This can’t come from Ottawa. It has to come from us — artists, writers, builders, teachers, parents.

Choose Leadership That Builds, Not Just Manages

We need to stop rewarding political caretakers and start electing nation-builders. Leaders who say:

"Here’s what we’re doing, and why."

"It will be hard, but it’s worth it."

"We’ll go together, or we won’t go at all."

This takes courage — and citizens who join the actual front lines of democracy, at boring and uncool party policy meetings on rainy Tuesday nights and Saturday mornings in the winter.

Learn to Live With Discomfort and Not Agreeing without Protest

A peaceful, prosperous Canada will never be a frictionless utopia. It will be a hard-won peace, forged through tension, compromise, and effort. That means:

Recognizing trade-offs

Accepting imperfect progress

Resisting the urge to burn down what we still need to fix

Learning that the frontline of a procedural and even participatory democracy is not at the barricades of the protest line, it is not at the ballot box, it is not at the public consultation, and is not in the gallery of City Hall or the Legislature. The frontline of our democracy is at the policy meetings, lunch fundraisers, and electoral district association meetings of the parties in the oligarchy of government.

The Word War

We’re not at war. But we’re not quite at peace either. We are in a cold civic crisis — of words.

The fix is not a single policy, party, or prime minister.

The fix is us. Citizens who remember that Canada is not just a place to live.

It’s a country, a nation, with a future to build — together.

It occurs to me that there are only a few ways to motivate people en masse. Wars/military, religion, businesses and family. Family is generally the smallest grouping (except maybe dynasties). So here's my radical idea to solve some of that unworkable mess, especially immigration, adoption. Yes, I'm aware I'm crazy and I don't mind reordering entire legal frameworks ground up without notice, but we need change and I did say once that I was a radical.

In order to immigrate, including as a temporary foreign worker (eg. crop picker), including as a new foreign hire at a job, including as an international student, you must be adopted by a Canadian. That person now becomes responsible for you, your housing, your job, your medical care, your socialization, your language skills, etc. So there must be a high benefit to adopting too. Many benefits have to devolve to the individual doing the adoption, something like AI would have to map the correct students or foreign workers to a prospective adopter. I'm envisioning a system where the new immigrant and the new adopter are really the heart of a localized system bypassing Provincial politics almost entirely. It would also allow Indigenous to adopt as well, if that's something they wanted to do. There would also have to be a system to "divorce" the adoptee, both if things didn't work out for whatever reason and also due to need as well as. a system for the "adoptee" to move up to the rank of independent head of household (or "full" Canadian). Yes, they would live with you, yes they would work with you, yes they would go to school with you, yes to all of that. It would definitely be an adjustment. It would also "fix" some of the problems we have with immigration, allow people to have direct investment in new immigrants and all the social benefits and connections that might provide, as well as the hassles it entails. It would immediately engage everyone in this exercise.

If you want to really extend the idea then also make it so that no outside foreign entity can own any land or business. It all has to be Canadian owned, no exceptions. All that Chinese money buying empty condos in Vancouver, well now you can move in. You're welcome.

learn from what works-reward people directly for participation. not something for nothing but something for something. Some Indigenous people do this all the time and they expect to be gifted, feasted...or they won't show up. Isn't it strange that we pay our representatives rather well (whether they actually represent us accurately or not) but we are expected to do our civic participation gratis? could do this with 16 year olds...paid civic education + they get heard. elders might feel included and respected for a change. moms & dads...with babies, toddlers, (having kids in the room reminds folks what this is all about). this IS happening here & there with non-profits (no cash but really good & generous food), very exciting, but I don't think any Parties have adopted the strategy. once in a while a municipal public consultation session comes close (MODL did a good one around the idea of a food-hub recently). Regular Town-Halls as a required part of Provincial and municipal policy decision-making would be good.