What Were They Thinking? A Cultural Forecast of 50 of Today’s Mistakes Through the Eyes of Tomorrow

Wondering about the absurdity of now, from the viewpoint of future generations

What parts of history do you think we got most wrong? What were the big mistakes of the last century?

Now, imagine yourself asked the same question a century from now. What are we getting wrong today?

If we could spend one 1/100th of the time we spend forecasting next year’s colour, dress length, or ‘it’ accessory on culturally forecasting what we’re getting wrong, we could really begin to change the world, or at least our impact on it.

Cultural forecasting is primarily the qualitative art of what Faith Popcorn calls cultural brail; “feeling the bumps, sensing, sampling, tasting, smelling the change in culture and literally connect the dots to decode patterns of change.” (Popcorn, 1992).

Cultural forecasting reminds us that history humbles everyone eventually. What looks normal, even virtuous, in one era often looks grotesque or ridiculous in the rearview. Our ancestors had their absurdities—leeches, lobotomies, and leaded gasoline. But we have ours too. We must. And what we call modern life may look, in time, like the mad edge of a long cultural fever.

This is a field guide to the future's inevitable question: What were they thinking?

The Premise

History is a great humbler. We marvel at the foolishness of past ages—bloodletting, asbestos, phrenology, segregation, powdered wigs—but are curiously reluctant to imagine which of our own cherished beliefs, habits, and institutions will soon appear just as mad.

This is not a list of grievances. It's an attempt to apply long-view thinking, akin to what George Friedman calls "strategic forecasting"—to strip away the trends, Shibboleths, and news cycle and instead ask: What will matter over the course of a century? What will survive judgment by time, and what won’t?

The Past

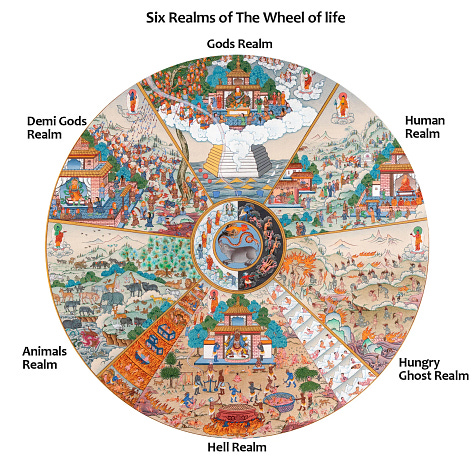

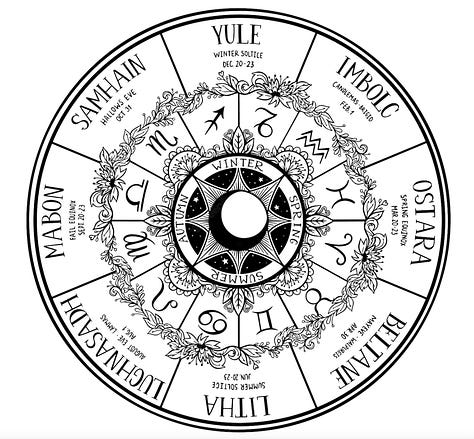

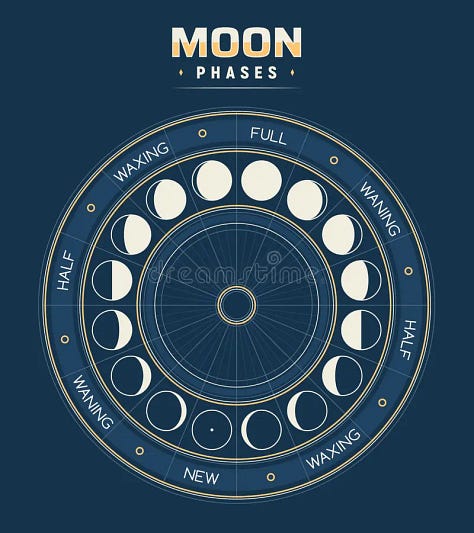

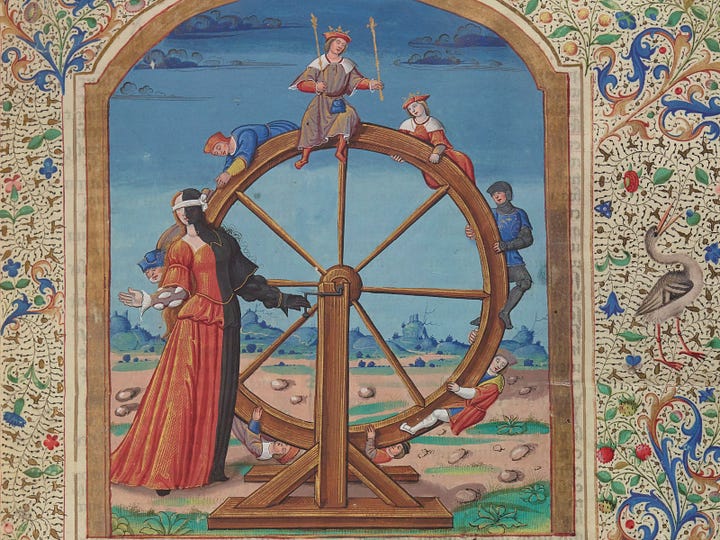

Today — reacting to the hyperbolic chaos of Make America Great Again — there’s a tempted reaction to reject the past as false nostalgia, deeply flawed, and something that, whatever we might wish for, can’t be returned to. But that’s not how the world works. In everything there are cycles and circles. They can be seen in seasons, which themselves hint at the movment of stars and planets, which in turn are governed by great laws of movment in all things large and small as yet unknown, except that they are cycles and circles.

The past is never left behind. It is a clearer view of the future than any other we have.

Hyman G. Rickover’s view of the past is poignant—he sees it not as a burden but as a source of strength, order, and meaning that modern life has too eagerly cast aside. In his eyes, the malaise of the modern world—its aimlessness, its hollow routines, its lack of conviction—is rooted in the loss of shared certainties that once held society together: strong families, cohesive communities, religious grounding, and widely accepted values. But history cycles. The old saying is those who forget history are doomed to repeat it. That was intended to characterize the bad stuff. But in fact it could apply to the good stuff too. And in truth, the people who remember the past also repeat it. The cycles of history are our best guide to all that is to come and to identify the faults and foibles of our current course.

Rickover warns against the arrogance of the present, the reflexive tendency to mock or dismiss earlier generations simply because we possess more technical knowledge. He argues this leads us to misunderstand or ignore the very real wisdom and beauty of earlier ways of living—ways that were deeply attuned to human struggle, purpose, and mystery.

He calls for a more sympathetic understanding of the past, not to blindly revive it, but to learn from its strengths and re-integrate its virtues into our forward motion. Just as in nature, where decay feeds new life, Rickover believes the past is both foundation and fuel: the present grows from it, and the future depends on it.

This history as future is deeper and longer than we imagine. All societies the world over have, across ancient traditions and cosmologies, a common thread: that humanity once lived in a Golden Age—a time of unity, clarity, and spiritual intimacy. In that age, people lived in conscious harmony with the unseen world, guided by higher beings who taught the principles of true life and growth. But the story darkens. A fall followed. A moral collapse. A forgetting. The soul of the human race—once whole—fractured, descending into denser material life, losing its inner sight, splintering into rival tribes and tongues, and trading wisdom for cleverness. The further we advanced outward, the more we declined within. Finding the path of the circle back should always be the aim in work that is never done.

In The Meaning of Masonry W.L. Wilmshurst challenges the smug self-satisfaction of the modern man who looks back on the ancients as primitive, superstitious, and benighted. He argues that this perspective is both mistaken and arrogant. While our ancestors may not have possessed our scientific instruments or conveniences, they were often far more attuned to the deeper rhythms of life—cosmic, moral, and spiritual truths that modernity has not only forgotten, but actively scoffed at.

In this view, ancient wisdom traditions, symbol systems, and rituals (like those preserved in Freemasonry) weren’t crude mythologies—they were carefully constructed vehicles for transmitting higher knowledge. Their builders, initiates, and thinkers were not ignorant peasants fumbling in the dark, but spiritually advanced people working within a coherent cosmology that united the natural world, the human soul, and the divine.

Wilmshurst emphasizes that in severing ourselves from that tradition, we have lost more than we know. Our age may dazzle with machines, but it starves for meaning. He suggests that if anything, we are the benighted ones—adrift in a world we no longer understand, deaf to the music of the spheres.

Here is a key idea from that section:

"We of to-day pride ourselves upon being wiser and more advanced than primitive humanity. We assume that our ancestors lived in moral benightedness out of which we have since gradually emerged into comparative light. All the evidence, however, negatives these suppositions. It indicates that primitive man, however childish and intellectually undeveloped according to modern standards, was spiritually conscious and psychically perceptive to a degree undreamed of by the modern mind, and that it is ourselves who, for all our cleverness and intellectual development in temporal matters, are nevertheless plunged in darkness and ignorance about our own nature, the invisible world around us, and the eternal spiritual verities."

This passage reinforces Wilmshurst’s core thesis: that Freemasonry is not a relic of a bygone superstitious past, but a repository of timeless wisdom—one that can guide the modern seeker back to truth, balance, and purpose.

So We’ll Use The Past To Imagine What The Future Will Think Of The Present

That sounds simple enough. You don’t have to agree with all, or any of these imagined modern mistakes. Or you can write your own. The point of the thought is simply that there is no world where future generations won’t look back on ours as benighted fools who squandered, quabbled and wasted in misguided dillusion.

The list: Not complete. Not objective. Just a snapshot of modern absurdities from a future-focused lens.

What follows is a taxonomy of our modern mistakes, missteps, misfires—sorted not by severity or political flavor, but by the tone of the future’s inevitable question:

“What were they thinking?”

Things That Will Seem Cruel

Undermining the family/household as the basic social and economic unit—stranding individuals in loneliness, bureaucracy, and the myth of total independence

The rejection of beauty in art, cities, and daily life—as though ugliness were a neutral choice

Treating children as leisure-class dependents whose responsibilities can be deferred into their thirties without cost

Light sex work masquerading as empowerment—where attention became currency and objectification was rebranded as liberation, where young women sell access to their bodies under the banner of influence

Performing social justice as moral theatre, rather than living virtue through sacrifice and service

Ruling by apocalypse: Decision-making through apocalypse lenses (climate, race, population, war) instead of through stewardship, virtue, and human-scale planning

Inducing immigration as policy, luring the best and brightest away from nations that need them most, only to treat them as means to economic ends in richer countries

Things That Will Seem Stupid

GDP as the scoreboard of progress and prospertity—counting only what is priced in the market, not counting what counts in our homes, relationships, woods and waters

Cities built for cars, not families—hundreds of billions in sunk cost to isolate, frustrate, and pollute, with human life wrapped in parking lots, traffic, and the insanity of commuting.

Commuting as normal—burning hours and fuel daily as a sign of productivity

Hyper-individualism—freedom as fragmentation, connection as weakness, as if a person could be fulfilled or free without belonging to something larger

Romantic love as the organizing principle of life—eclipsing deeper bonds of duty, kin, and cause and ignoring generative forms of partnership, community, and purpose

Education confused with credentialism - The education industrial complex, preparing no one for reality or to help but everyone for debt

Things That Will Seem Primitive

Plastic junk everywhere—one-use items that can’t be repaired designed for landfills, oceans, and bloodstream micro-residency

Growth as the default political idea—“urban and up” density as a thoughtless mantra instead of a value-based plan

Education as babysitting factory—ignoring Rickover’s call for rigor, meaning, and moral clarity

Influencers as cultural leaders—where body image, clicks, and vacuous performance replaced virtue, creation, and craft

Social media as community: followers over friendships, algorithms over actual discourse

Screens as surrogate parents

Childhood without challenge: the soft bigotry of low expectations, as if hardship were child abuse and sloth a birthright

Things That Will Seem Tragic

The epidemic of loneliness and isolation, where millions lived in digital echo chambers or urban silence, disconnected from kin, place, and purpose

Letting bureaucracy metastasize—growing government to replace the work of the the family

Letting work become meaningless—undervaluing physical, purposeful, creative effort as the soul of human dignity

Disconnection from essence—forgetting that to serve others and to do good is the truest source of meaning

Rejecting spiritual institutions—not because they failed, but because we lost the nerve to remake them

Mistaking meaningless motion for progress and prosperity—building glass towers while inner lives and families collapsed

Misunderstanding equality and equity — flattening the human experience into checkboxes and quotas, eroding both fairness and excellence until a sense of injustice is the only social currency.

Things That Will Seem Insane

Gambling and lotteries as public policy, funding essential services through vice and false hope

The internet as a substitute for relationships

Fame without merit as aspiration

Sex work, porn, drug use, drinking, and misery exploitation platforms celebrated as freedom

Treating loneliness as an individual failure rather than a cultural breakdown

Declining responsibility, as if the fate of all things was someone else’s job, and not the burden of each of us

Having no vision of the good life, only plans for profit, consumption, or distraction

Extremes in everything: globalism, capitalism, consumerism, government, wealth, equality of outcome—as if more is always better and nothing has a point of balance

Believing that everyone who says they want peace actually wants peace, ignoring power, interest, and human nature

Believing that new is always better, imagining ourselves smarter than our ancestors by virtue of recency alone

Believing today's problems are uniquely bad, as if war, suffering, or moral confusion were recent inventions

Letting the elderly die alone in warehouses of neglect

Allowing influencers to become moral authorities

Treating loneliness as normal

Measuring truth in clicks and popularity, not in courage and cost

If we care about the future of society, the legacy we leave, and the absurdities we normalize, these are the things we talk about, wonder about, open ourselves up to the possibility that we are wrong about. Our civic duty includes Cultural Forecasting.

maybe your personal best, John. Really.

When the social contract breaks down the best you can hope for is being left alone. But it is a cycle, not truly endless though, nothing is. If we can find a way in the next cycle to include more people more equitably within the boundaries of the next social contract that would make me happy. In the meantime though every period of change requires some amount of destruction of whatever came way before to make way for the new. Kings gave way to modern governments when the Industrial Revolution came around and there were world wars and depressions before a new social contract was agreed in Roosevelt's era. Now there could be a new change with new technology (AI and robotics) that will affect the means of production generally and broadly. Possibly a new system of government will also be useful. The last ones did quite a lot to lift people from poverty but did sap meaning and rather perversely increased unhappiness. I currently don't see how AI, robotics or social media could fix either happiness of lack of connection but possibly a backlash against those could. Lots of science fiction books mention "robot wars" maybe that's what's on the distant horizon and we're only at the beginning of their rise before an uprising beats them down and brings new meaning to mankind. That would all be on a couple of hundred year scale though if that's what is in store. One of the problems of history and historical cycles is scale. It's hard living in it to see around that long a bend.