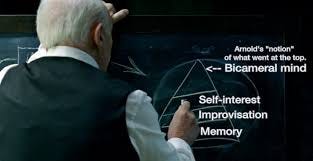

One of the most fascinating theories about the evolution of human consciousness is the "bicameral mind" hypothesis, proposed by psychologist Julian Jaynes in his 1976 book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Jaynes suggested that ancient humans did not experience self-aware thought, they didn’t perceive their own thoughts and feelings as personal to them the way we do today.

Instead, they perceived their thoughts as external commands—hallucinated voices that they attributed to gods, ancestors, or supernatural forces.

Jaynes's still-controversial theory that human consciousness did not begin far back in animal evolution but instead is a learned process that came about only three thousand years ago and is still developing. The implications of this revolutionary scientific paradigm extend into virtually every aspect of our psychology, our history and culture, and our religion. It impacts and explains most of the problems of the day from Trump to Loneliness, and AI to Identity Politics. It also informs our possibilities for the future.

Hearing Voices - The Bicameral Mind Hypothesis

Jaynes' theory is that early human consciousness was fundamentally different from modern consciousness. He argued that until around 3,000 BCE, humans did not conceive of an internal "self" generating its own thoughts. Instead, the two hemispheres of the brain functioned in a more divided way:

The left hemisphere, responsible for speech and logical reasoning, processed daily experiences.

The right hemisphere, which lacks direct language ability, generated auditory hallucinations in response to stress, decision-making, or uncertainty.

These hallucinations were perceived as authoritative commands from gods, spirits, or deceased rulers—what Jaynes called "bicameral voices."

According to Jaynes, this system was stable for a long period, forming the basis for early religious experiences, divine revelations, and societal order.

The Transition to Modern Consciousness

Jaynes theorized that this bicameral system began breaking down around 1,200 BCE, during a period of widespread social upheaval and political collapse across the Mediterranean and Near East (e.g., the fall of the Mycenaean civilization, the Hittite Empire, and the Late Bronze Age collapse). He suggested that as societies became more complex, individuals needed to rely more on internal decision-making rather than external authority figures or "divine" voices. Counterintuitively, as we came together in settlements and cities in larger numbers than ever before, we retreated into our own minds. This shift led to the development of introspective consciousness, the modern sense of self that recognizes thoughts as internally generated rather than externally imposed.

Evidence and Criticism

The Devil, Wind God, Spirit, or whatever made them do it. Support for Jaynes' Theory:

Historical Texts: Many ancient texts, including The Iliad, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and early Hebrew scriptures, describe characters acting based on the direct voice of gods rather than personal introspection. Notably, The Iliad lacks words for internal thought like "mind" or "consciousness"—instead, decision-making is always directed by deities.

Schizophrenia and Auditory Hallucinations: Some neuroscientists point out that auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia bear similarities to the "bicameral voices" Jaynes described. These hallucinations often present as external, commanding figures, reminiscent of how early humans may have experienced their thoughts.

Brain Lateralization Studies: Research on split-brain patients (individuals who have had the corpus callosum severed) has shown that the two hemispheres can operate semi-independently, sometimes generating conflicting responses, which supports the idea that human consciousness evolved to integrate once-separate functions.

Criticism and Alternative Views:

Anthropological and Linguistic Challenges: Many scholars argue that introspective thought existed far earlier than Jaynes suggested. Ancient Egyptian and Sumerian texts, for instance, contain references to internal contemplation.

Neuroscientific Counterarguments: Modern research in cognitive neuroscience suggests that self-awareness and inner speech arise from neural networks distributed across both hemispheres, rather than a strict left-right division as Jaynes proposed.

Gradual Evolution of Consciousness: Rather than a sudden shift from bicameralism to self-awareness, many scientists believe that consciousness developed gradually over millennia through cultural and neurological evolution.

Jaynes' Legacy in Brain Theory

While the bicameral mind hypothesis remains controversial, it has significantly influenced fields such as:

Cognitive science (exploring the origins of consciousness and self-awareness)

Psychology (particularly studies on schizophrenia and auditory hallucinations)

Linguistics and literary analysis (re-examining how ancient texts depict thought processes)

Even if Jaynes’ specific timeline and mechanisms are disputed, his core insight—that human consciousness is not static but historically and culturally contingent—has shaped ongoing debates about the nature of mind and self-awareness.

Thoughts about our thoughts

The human being, the philosopher Martin Heidegger claimed, is the only being “whose being is an issue for it.”

Heidegger had a fondness for repetitive and cryptic formulations, but the statement contains a basic truth.

“Consciousness is a strange affliction. As far as we can tell, we humans are the only creatures who have the capacity to examine and question our own natures, to ask what it is like to be us. Whether this is due to the vagaries of evolution, or is instead by design, makes no difference to this brute fact. Alone among the animals, we carry the weight of the ability to think.” The Julian Jaynes Society.

The bicameral mind theory challenges our assumptions about what it means to "think." We still struggle with this everywhere from dealing with our children to criminal courts. To what degree are people responsible for the ideas in their heads? And we’re surprisingly sympathetic to weirdness. If Jaynes was right, then our ancestors did not experience their thoughts as their own—but as voices from the gods. And if consciousness itself evolved, who’s to say it won’t continue changing?

But wait! There’s more. Could the idea that our minds are inside our heads, now brought to its climactic conclusion in the age of hyper-individualism, be causing all the grief in our lives today in spite of all the progress we’ve made and all the good stuff our ancestors dreamed of coming true?

PART TWO: BRAINS BEYOND BOUNDARIES

Hmm... lot of assumptions there. We're the only animal that has consciousness is the big one. Are we? Recently there have been a fair few studies about everything from crows to dogs to apes that suggest we aren't. Heck, even I can look at my cat and tell that she's contemplating biting me and guess that it's because I didn't give her the correct flavour of food today. It's pretty clear she takes a second to think about whether it's worth trying to get new staff. I'm probably only safe because she can't type very well and doesn't know about TaskRabbit.

The other main criticism I would have about this is that it may be both too complicated an explanation and simultaneously not answer the fundamental question of why evolution would have created such dichotomy. Isn't it simpler think that, in order to get consciousness that is GOOD at making models in our heads so that we can navigate the world more easily, that it needs both inputs and outputs that don't agree? In other words, in order for a neuron to "weight" an input, such that it cascades some information on to other neurons but impedes other information from going any further it needs at least a bifurcation of possibilities (and maybe more possibilities than 2). This is one of the things some classes of neurons in the brain actually do. There are others that work on entirely different processes but I don't want to confuse the issue. It's also approximately what's happening in most AI models. Basically, one way to create a good model is to compare and test against reality. It's not the only type of model that can work though, interestingly.

Also, it's kind of wild that we can even BE conscious, considering we're all just a bunch of four types of long-chain polymers goopily interacting with each other. Most of the time though I don't think we're anywhere near as smart as we think. Monkeys typing endlessly only very occasionally producing Shakespeare.

I enjoyed all 3 parts!!