What the Leaders Debate Revealed About Power in Canada

Fear. You could see it in their faces. You could hear it in every careful word. Who Were They Afraid Of?

It’s Easter, and I’ve been thinking about angels — not the Hallmark ones, but the real ones. The ones in scripture who appear not as soft-winged comforters, but as beings so otherworldly, so radiant and true, that the first words out of their mouths are always the same: “Don’t be afraid.”

It happens on Easter morning, at the tomb, when the Marys and other women find it empty and the world suddenly turned upsidedown.

The angel is there not to explain, not to instruct, but to steady them. Fear, of course, has always been part of us — older than language, deeper than reason. But that line — “don’t be afraid” — is the most repeated command in all of scripture, which should tell us something. The sacred doesn’t arrive through fear. Fear is what blocks the good with the bad. Fear is what freezes the world in place. And those who rule through fear, whether ancient tyrants or modern bureaucrats, are not bearing divine news. They are just afraid themselves.

CTV NEWSCAST: “Michelle Cormier who's the executive director of the leaders debate commission did go before reporters to say that yes in fact they would not be able to hold them saying that they didn't feel they could actually properly guarantee a secure environment.

And then following that we were outside here when we saw a number of members of the media who were following uh some of these leaders around the country.

They were being followed by some of these right-wing media outlets who did the previous night monopolize some of the questions from the leaders debate at those press conferences from the French language leaders debate and it started to get testy…”

Let’s say it straight. Zero politicians in Canada are afraid of getting asked questions. But they are afraid. They’re afraid that a question — any question — might lead them to say something unscripted, something outside the approved moral code, something that doesn’t pass the test of tone, phrasing, or ideological cleanliness.

They’re not afraid of being wrong.

They’re afraid of being unclean.

They’re afraid of being misunderstood — on purpose.

Of being clipped, quoted, framed, and posted into the digital stocks by people whose power doesn’t come from ballots, but from consensus control.

They are afraid that the questions might result in them saying words that could offend the wrong people — not voters, not opponents, but the unofficial class that polices language, assigns motives, and decides who’s safe to listen to.

That’s the fear we saw on stage.

And the reason it matters is because it isn’t just their fear. It’s ours.

Because when leaders can’t speak freely, citizens start learning to stay quiet too.

I watched the Canadian federal leaders debate. What struck me wasn’t the heat of the exchanges or the sharpness of the arguments. It was the fear.

I didn’t see powerful men. I saw men afraid of saying the wrong thing, men cowed by an unseen power, men repeating pre-approved phrases like catechisms.

In fact, the three main party leaders were distinguished less by their ideas than by the particular style and level of obsequiousness with which they performed.

Poilievre, often seen as the rebel, played the part of the exasperated office manager — clearly resentful, but still careful never to step directly on linquistic landmines.

Carney, the candidate of systems and signals, delivered his lines with the smooth precision of someone who’s lived among the palaces and understands their rules — a man more likely to manage the mood than challenge the ideology.

And Singh, once set to be the voice for working people, now seemed fully absorbed into the ritual — all signal, no threat, no noise, a supplicant whose moral vocabulary is perfectly tuned to the system he once claimed to confront.

Together, they weren’t offering competing visions of the future.

They were auditioning to speak on behalf of the same worldview — each hoping to be its most fluent, most trusted translator.

And they were afraid.

They weren’t powerful. They weren’t vying to lead. They weren’t even trying to represent mainstream voters. They were trying to please. To show that they could best embody the tone, the language, the moral vocabulary of another power entirely — one that wasn’t on the stage but hovered over it like a silent sword of Damocles.

What I’ve been thinking about in the days since the debate is how to find a new understanding of that power.

That power isn’t a party. It’s not the press. It’s not the bureaucracy — they are more afraid than anyone. It can’t be described in left or right terms, liberal or conservative, working class vs. rich. It doesn’t have a clubhouse. And it’s new. It’s growing and changing. But it’s not a conspiracy. It might not even be intentional or self-aware.

It’s something older and newer at once. For the difficult purpose of this exploration to work out what they’re all afraid of, what this new power is, I’m going to call it Canada’s progressive clerisy.

SIDEBAR: The "sword of Damocles" is an idiom referring to a constant and imminent threat or peril, often used to describe the precarious situation of those in positions of power. It originated from a story about Damocles, a courtier who was seated beneath a sword suspended by a single thread during a banquet, symbolizing the danger and insecurity that can accompany power.

Who Has Power?

Here’s a simple test. You can use it in any setting. Do it as a thought experiment for the whole country or apply it to your grade school class or family gathering. Power is ethereal. It can move astonishingly fast. It is rarely where it officially seems to be. It is often hidden.

So this is the test:

Ask yourself, who would you be afraid to question? Who would you be afraid to speak out against? Who would you be unwilling to publicly doubt? More generally, who is beyond reproach in the public sphere?

Is it the police?

The Church?

Elected politicians? Parties?

The Cable Company or any other media company?

Is it the big corporations? Brands?

China? Or other countries?

The rich?

No. It’s none of those. That’s laughable. Anyone who has ever watched the late night shows, a PTA meeting, or attended a dinner party knows exactly who has the power.

The Clerisy Defined

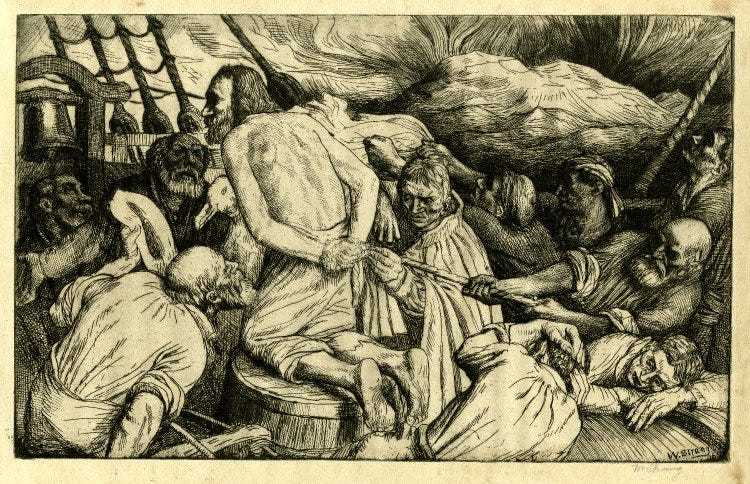

The word clerisy comes from 19th-century philosopher and poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He wrote the poems The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Kubla Khan. He coined it to describe a class of educated, thoughtful people — teachers, clergy, artists, intellectuals — who guided the moral and cultural life of society. Not by force, but by influence. Not by decree, but by shaping what was good, true, and beautiful.

Coleridge's Idea:

Coleridge, a prominent figure in the Romantic movement, envisioned a secular organization of intellectual elites to disseminate knowledge and shape society. He believed this group, the "clerisy," was crucial for societal flourishing.

Influence of German:

Coleridge adapted the term "clerisy" from the German word "Klerisei," which translates to clergy. He may have equated it with an older sense of "clergy" referring to learning or knowledge.

Distinction from "Intelligentsia":

Coleridge preferred the term "clerisy" over the later Russian term "intelligentsia," which he considered more narrowly focused, as noted by Merriam-Webster.

The New Clerisy

In recent years, writers like Joel Kotkin have revived the term to describe a new, distinctly modern phenomenon: an unelected class of highly educated, culturally progressive professionals who dominate Canada’s (and much of the West’s) institutions. This progressive clerisy now functions as a kind of secular priesthood — not enforcing doctrine through faith, but through language, policy, and cultural gatekeeping. They shape what is sayable, fundable, teachable, and respectable, not through law or force, but through consensus, shame, and institutional control. The term isn’t meant to insult — it’s meant to name a very real shift in who holds power, how it’s exercised, and why so many feel unable to speak plainly in public life.

The modern version still plays that role coleridge imagined — but with a new script. Today’s progressive clerisy is made up of public-sector professionals, NGO managers, university administrators, media editors, and the vast network of consultants, equity officers, and policy whisperers who hover around our institutions.

You won’t find them on the org chart (they can hold any or no position). They’re not elected. They don’t campaign. They don’t write laws. But they shape the language of those who do — and they define the boundaries of what counts as moral, modern, and respectable.

What Defines the Progressive Clerisy?

Key Traits of the Progressive Clerisy Class

Credentialed, but not necessarily productive

Degrees over outcomes. Paper over practice.Ideologically uniform

Strong alignment on climate, identity, decolonization, gender theory, anti-capitalism.Symbolic over material

More interested in how something is said than what it accomplishes. More concerned with language, gestures, and values than outcomes or delivery.Risk-averse and bureaucratically savvy

Masters of policy language, grantspeak, institutional process.Gatekeeping by soft power

Control via guidelines, norms, social and professional incentives — not laws.Morally certain, rhetorically soft

Harsh judgments wrapped in gentle language: harm, care, inclusion, trauma.Institutionally protected

Embedded in large organizations that reward ideological conformity and penalize dissent quietly. They don’t need power in a formal sense — they shape what’s acceptable, and thus what’s possible.

How Did We Get Them? A Quick Progression

Here's how the Progressive Clerisy Class evolved:

The Traditional Clergy & Scholars (Pre-20th century)

Held cultural power through the church, classical education, and publishing. Gatekeepers of spiritual and intellectual life.The Liberal-Humanist Intelligentsia (Mid-20th century)

Professors, writers, and journalists who shaped society through reasoned argument, pluralism, and Enlightenment values. Think Orwell, Hitchens, or Margaret Atwood in her early years.The Postmodern Academic Class (Late 20th century)

Relativism replaces reason. Identity, power structures, and “lived experience” become the new currency. The university becomes the engine room of a new worldview.The Progressive Clerisy (21st century)

Institutionalized across the public sector, education, arts, media, NGOs, and HR departments. No longer fringe. Now the dominant moral voice in elite spaces.

Clerisy vs. Democracy

Clerisy is calm, curated, and closed. It speaks in the language of consensus, credentialism, and moral certainty. It presents itself as above politics — too refined for partisanship, too correct for debate. Once its worldview is installed in institutions, it resists questions not with answers, but with process, paperwork, and polite exclusion.

Democracy, by contrast, is messy.

It’s an argument we have with ourselves — loud, local, and unfinished. It’s a running conversation about the rising generation and the shape of things to come. It speaks in the future tense. It invites disagreement and survives on friction. It needs towns, not just towers. Communities, not just campaigns. It needs many paths, many hands, many visions.

Democracy is a league, not a lecture.

It thrives when there are teams — parties, churches, unions, neighbourhood groups — each with their own playbooks, each with a shot at winning hearts and minds on the field of public life.

The clerisy doesn’t like leagues. It prefers codes.

It prefers all the teams to wear the same jersey — or be disqualified for poor sportsmanship.

But a society run by one worldview, no matter how well-intentioned, isn’t democratic. It’s administered.

And administration may keep things tidy — but it doesn’t keep them alive.

How They Hold Power Without Being in Power

This class doesn’t use hard authority. It doesn’t need to. To them political parties, community groups, chambers of commerce, churches and unions are just crass instruments of the past — noisy, transactional, stained with compromise. There places where ideas and voices can run free and untethered. To the clerisy, real authority doesn’t come from organizing people, winning votes, or persuading your neighbours. It comes from curating language, shaping consensus, and setting the boundaries of what’s acceptable to say in public.

Parties can lose power. Churches can lose followers. Chambers of commerce can close. Unions — once the great voice of working people — have faded from relevance, replaced by HR departments and advocacy groups that speak a very different language. But a worldview, once embedded in education, policy frameworks, institutional mandates, and cultural gatekeeping, becomes nearly unchallengeable. It floats above democracy, untouchable and unaccountable — and that’s exactly where the clerisy prefers to live: not in the arena, but above it, subtly managing the game.

It governs through consensus, language, and reputation.

It can’t jail you — but it can label you.

It can’t fire you — but it can make you unemployable.

It can’t outlaw your views — but it can make sure they never get funding, never reach a mic, and never get called back for a panel.

It operates across the CBC, school boards, universities, cultural grants, HR departments, and Ottawa’s inner machinery. You’ve likely never met anyone who says they’re part of it. But you’ve probably heard them speak — or watched others adjust their speech in real time to match the tone.

The result is what we saw at the debate: not a contest of ideas, but a performance of ideological fluency. Not conviction, but compliance.

Understanding the progressive clerisy is essential to understanding why Canadian politics feels increasingly performative — and why changing the leader so often changes nothing at all.

You can elect someone new. You can even change parties. But if the values, language, and incentives that govern Ottawa, CBC, Canada Council, the universities, and half the civil service are already locked in, you’re not driving the bus. You’re just picking the playlist.

This is not a conspiracy. It’s just a class — a class that believes it is right, has the institutions to enforce its rightness, and no natural predator except public skepticism.

And that’s why people are asking, with good reason, what would really change under Mark Carney, or anyone else?

Because until someone names the clerisy, confronts its unearned certainty, and dares to govern beyond its reach, the real operating system of the country stays exactly the same.

SIDEBAR: The Rime of the Ancient Mariner – Fear, Judgment, and Moral Reckoning

Coleridge’s poem is soaked in fear — of nature, of the unknown, of spiritual judgment. The mariner violates an unspoken moral code (killing the albatross), and suffers the maddening isolation of someone marked by invisible, inscrutable forces.

That connects strongly to modern social, political and bureaucratic fear — the fear of stepping outside the rules of the system, even if those rules are vague, shifting, or never explicitly stated. Like the mariner, today’s leaders are not punished by law but by consequence without clarity — social exile, reputational ruin, the equivalent of wearing the albatross around the neck.

“Ah! well a-day! what evil looks

Had I from old and young!

Instead of the cross, the Albatross

About my neck was hung.”

(Rime of the Ancient Mariner)

There’s an eerie echo here of political culture under the clerisy — where you can speak, but not freely, act, but not too independently, and where the real punishments are shame, isolation, and disqualification.

Canada’s Crisis of Democracy

Many Canadains won’t vote in the next election. Some will say it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t make a difference. For them, voting is just not doing the thing it was once imagined to do.

Canada’s biggest threat isn’t populism, polarization, or even debt. The climate change and sea level rise. The equity and inclusion. All these issues. all real and important. They conceal more than they reveal.

It’s a quiet breakdown of institutional credibility — a growing sense that no matter who we vote for, the country is governed by people we didn’t elect, following ideas we didn’t debate, in service of priorities we didn’t choose. This isn’t a crisis of politics. It’s a crisis of democracy. And the first step back is learning to name the system that’s taken its place.

Canada is facing:

A loss of public trust in government

Declining productivity and rising cost of living

Institutional failure in housing, healthcare, immigration

A shrinking sense of national unity

A falling birth rate and growing social fragmentation

An electorate more anxious than angry

Citizens who’ve given up believing… in anything.

The question isn’t who to blame, but what’s not working — and why do so many of our smartest, best-resourced systems produce results that feel so... underwhelming?

That’s where the concept of the clerisy comes in — not as a conspiracy, but as a diagnosis.

The federal debate last week — like so much of Canadian public life these days — was defined not by what was said, but by what couldn’t be said. The whole thing felt like a polite performance inside a glass box. The candidates jostled over housing, affordability, climate, and healthcare, but all within a narrow range of acceptable language, pre-cleared values, and morally fashionable positions. It wasn’t that the conversation lacked intelligence. It’s that it lacked permission to wander beyond the lines drawn by an invisible, unelected presence hovering just offstage.

It’s not about the elephant in the room — that metaphor’s too big, too obvious. This was more like a velvet rope: quiet, soft, but absolute. A social boundary policed by Canada’s progressive clerisy class — the cultural managers, bureaucrats, and moral regulators who now define the limits of political discourse in this country. You don’t see them on the stage, but you see the imprint of their ideology in every word that gets said — and more importantly, in every word that doesn’t.

The real debate we need — the one voters are dying to have — isn’t left vs. right, or even growth vs. austerity. It’s elected power vs. unelected influence. It’s whether we live in a democracy or a managed consensus. Until someone on stage names the clerisy and challenges its grip on our institutions, every debate is just a scripted disagreement between pre-approved opinions.

Representative Govenrment

The fear on the debate stage wasn’t just personal. It was representative.

These men — polished, powerful, prepped — were not speaking freely. They were managing risk. You could see it in the pauses, the hedging, the preambles before every answer. They weren’t afraid of each other. They were afraid of saying something that would make them unfit to be included — not by the public, but by the people who define what "inclusion" even means.

And in that, they mirrored millions of Canadians watching from their living rooms.

Because we feel it too, don’t we?

We’ve learned that speaking plainly — about crime, immigration, gender, public safety, taxes, race, the family, climate — can get you labeled, flagged, shunned, or professionally iced out. You might not be cancelled outright, but you'll find your voice no longer welcome at the table. That job opportunity disappears. The invitation gets quietly rescinded. You’re not fired — you’re just out.

What’s replacing open disagreement in Canada isn’t censorship. It’s strategic silence — the kind that creeps in when ordinary people decide it's better to say nothing than risk being branded.

The leaders on stage knew that. That’s why they were cautious, almost haunted.

Because we now live in a country where the wrong word doesn’t get debated. It gets disqualified.

Not for being untrue — but for being unapproved.

That’s the real power of the clerisy.

They don’t need to arrest you. They just make sure you’re no longer included.

The bureaucracy is not afraid of the public.

It is not afraid of failure.

It is not even afraid of political change.

What Is Canada’s Bureaucracy Afraid Of?

It’s not voters, not Parliament, not even failure — it’s the progressive clerisy

I’ve written a lot about bureaucracy — about its growth, its caution, its obsession with process over outcome. But I keep returning to a question that gnaws at the edge of every policy failure:

What are they afraid of?

Because they are afraid. You can feel it in every document that’s been over-reviewed, every absurdly safe press release, every decision that’s been deferred for months because no one wants to “get it wrong.”

At first, I thought they feared the public. But they don’t. Elections come and go. Ministers come and go. Even scandal comes and goes. And the bureaucracy stays.

So what are they afraid of?

I think I’ve finally got the answer: they fear the clerisy.

That soft-spoken, sharp-edged, highly educated class of progressive cultural managers — not elected, not accountable, but ever-present.

They fear being labeled by it.

They fear being out of step with its language.

They fear being “called in” by its spokespeople.

They fear being the subject of a Slack thread or a social media whisper campaign that questions their moral posture.

Because that’s the only thing that can truly damage a bureaucrat in today’s system — not being wrong, but being problematic. Not failing, but offending. Not inefficiency, but insensitivity.

The clerisy doesn’t run the bureaucracy. But it has its attention. It sets the tone. It defines the risk. And once you see that, you can start to understand why nothing controversial ever gets done, even when it desperately needs to be.

The bureaucratic state is a vast, armored vehicle — but it will swerve wildly to avoid a hashtag.

Why This Matters — And Why It’s Not Paranoia

This isn’t a conspiracy. It’s a class.

And like all dominant classes, it eventually becomes blind to its own power.

The clerisy believes it is defending compassion, justice, and inclusion. But in doing so, it often shuts down legitimate disagreement, flattens cultural nuance, and cuts off ordinary people from the political conversation. It governs with the voice of progress but the instincts of a closed church.

When every politician is afraid of offending the same invisible tribunal — when no one on stage can name, let alone challenge, the worldview that governs them — we’re no longer watching a democratic process. We’re watching a performance with nice lighting.

Shame at Scale

How the progressive clerisy turned a private feeling into a public weapon

Shame used to be local. It came from your family, your neighbours, your church, your team, your community. It was intimate. It was shaped by shared values, and while it could be harsh or misguided, it was at least relational. You were held accountable by people who knew you.

Now? Shame is broadcast, abstracted, and weaponized.

It doesn’t come from someone who loves you. It comes from a stranger’s quote-tweet. From an HR policy. From a thousand-likes-deep pile-on you never saw coming. From a journalist who never calls, or a committee that never met you, or an algorithm you didn’t know you triggered.

And this is where the progressive clerisy thrives.

This class — fluent in institutional codes, moral frameworks, and therapeutic language — has mastered the art of using moral shame as a means of enforcement. They don’t debate. They signal. They don’t argue. They curate. They don’t disagree. They discipline.

Their weapon isn’t force. It’s implication. The careful raising of an eyebrow. The rewording of a policy. The subtle suggestion that your ideas — your voice — might be “unsafe,” “harmful,” or “problematic.”

It’s not a legal process.

It’s not censorship. It’s a deliberate use of shame to disqualify dissent — without ever appearing to shut it down.

From Local Morality to Global Compliance

The real shift is this: shame used to be based on shared morality. Now it’s based on shifting ideology.

There’s no agreed-upon centre. No roots. Just a constantly updating cloud of acceptable beliefs, mediated by a professional class of cultural technocrats.

This is what makes the clerisy so powerful: they manage the conditions of belonging.

Not through fear of jail or fines — but through fear of shunning.

If you say the wrong thing, it’s not that you’re punished. It’s that you’re made unwelcome.

Not you’re wrong — you’re not one of us.

That’s a potent fear. Maybe the deepest one in modern life.

And it’s why so many people — leaders included — will do anything to stay on the right side of the clerisy’s moral weather vane.

What Are We Afraid Of?

What Should We Do With This?

We give it a name. Calmly, clearly, without spite or drama.

Then we talk about it. And in that talking we often struggle, we argue, we say the wrong thing, we take different paths because we acknowledge the road is long and wide and there’s room for all sorts of ideas.

Because this isn’t a conspiracy. It’s not even new. It’s just the same old habit of people with power finding new ways to hold onto it — this time through language, through process, through unspoken rules about what you’re allowed to say.

It’s only controversial because we’re not supposed to notice.

It survives by being everywhere — and by never being named.

But democracy depends on us naming things. Talking plainly. Asking who’s in charge, and whether they’ve earned it. It means voters leading, not just professionals managing. It means politicians who speak like citizens, not spokespeople.

This isn’t dangerous. It’s basic.

If that makes us sound a little out of step, so be it.

But maybe we’re not out of step.

Maybe we’re not out of step enough.

French Canadian artist Eric Nado makes a strong statement about the power and impact of WORDS through his reconfiguring of vintage typewriters into sculptures of machine guns. Each piece has the ghosts of hundreds of thousands of messages and stories permanently embedded into their rollers.

The artist used lyrics from The Hip’s song “Poets” as inspiration for this triptych, and spells out each word using recycled keys.

So much to think about with this brilliantly provocative collaboration of word, machine, and imagination but for me the message is in the final lines of the chorus. Like the angels said, don’t be afraid. It’s not that we’re speaking out of turn, it’s that we’re not speaking out enough:

“Don't tell me what the poets are doing

Don't tell me that they're talking tough

Don't tell me that they're anti-social

Somehow not anti-social enough”.

To speak truth to power means to say something honest, often uncomfortable or critical, directly to those in authority — especially when doing so carries personal risk. It implies moral courage: telling the truth even when the powerful would prefer silence or flattery. It’s the act of confronting injustice, hypocrisy, or corruption with integrity and words.

It's not just critique — it’s conscience in action. The phrase is often associated with nonviolent resistance, civil rights, and has been co-opted by social justice movements.

The phrase first gained widespread currency in 1955 when the American Friends Service Committee (a Quaker organization) published a pamphlet titled:

"Speak Truth to Power: A Quaker Search for an Alternative to Violence"

The pamphlet argued for peaceful resistance and diplomatic approaches during the Cold War, offering a moral alternative to nuclear escalation and militarism. IT was an alternative to the accepted diplomacy industry of the day. It framed the act of truth-telling as a civic and spiritual duty, not just political dissent.

What Does “Bearding Power” Mean?

The essence of bearding power is about speaking truth to power— which is an old expression meaning to confront, challenge, or defy authority directly, often boldly and in its own domain.

The phrase likely stems from the old idiom “to beard the lion in his den,” meaning to confront a powerful figure on their own turf — to challenge them where they are strongest, and most comfortable. It conjures the image of someone daring to tug on a lion’s beard — a move both foolish and brave — depending on your level of preparation or desperation.

So, to beard power is:

To call out or challenge authority to its face.

To confront someone powerful in their own space — like speaking against a king in court, or testifying against a corrupt official in public.

To take a stand when silence would be safer.

Or as Canadian John Ralston Saul said,

The citizen's job is to be rude - to pierce the comfort of professional intercourse by boorish expressions of doubt.

Wow, there is a lot to unpack here.

Start with the fear at the debate itself… it was not the candidates who were in any danger specifically but the journalists, due to improper credentials given to Rebel News and True North at the French debate and the revocation of same at the English debate. Rebel News and True North are NOT engaged in journalism… they are registered with Elections Canada as third party advertisers. Did you watch the French debate and questions after? I did and I could not believe what I was seeing… asking Carney’s how many genders there are? What relevance did that have to anything? Carney gave more credit that it was due by answering “ there are two sexes”. The objective there was to try and generate some quotation that Rebel News could generate revenue from, not to forward a debate about issues relevant to the election.

Prior to the English debate Ezra Levant was removed from the journalist space and I gather from reporting that he made a fuss about it sufficient for the debate organizers to call off the questions.

As for fear of taking questions, there is one guy who will NOT answer questions from accredited journalists unless they are from friendly sources and where the questions have been vetted in advance—that is Poilievre, who has taken Harper’s strict message control to a whole new level.

What we desperately need is more fact checking and reporting of facts instead of opinions about the facts.

You mention climate… there is such a thing as climate *science* and if you delve into it you will understand the degree of peril we are in NOW. It is an uncomfortable topic and people would rather not face it but you can’t argue with physics.

I think we do need to have some honest conversations about what is denigrated as “wokeism”. The Quakers to whom you refer were the “woke” group of their day, pushing for an end to slavery and for women’s rights to vote and to equally participate in society. Maybe we can have a conversation about that.

Thank you for this. Such a rich overview of how we got here. I don’t study these things. I teach dance. I chair my local community association and sit on the Board of our local theatre. It amused me and horrified me that someone called out at a Carney rally, “Big daddy! Lead us forward!” We do seem to want to have some father figure take care of business and not do the uncomfortable work ourselves of getting involved at grass roots levels. I’m going to an all-candidates meeting tomorrow where the PC incumbent is ‘not able’ to attend. So I’m going to think on what you’ve said here and see if I can craft a question that speaks truth to the blah blah of careful platforming. Hmm. A challenge. Thanks for waking me up to relevant ideas.