We Gotta Talk About The Fall Of Rome

If anything, America is more like the Byzantine Empire than Rome in decline: a nation capable of reinvention, thriving under pressure, and innovating in the face of challenges.

The "Fall of the Roman Empire" is a modern concept that misunderstands the lived experience of the people who were part of it. For them, life likely felt like a series of gradual changes, progress punctuated by periods of upheaval, challenges, and change - kind of like all of history.

Rome Wasn’t Built in a Day, and America Isn’t Falling in One Either

The doomsayers seem to come out strong in the new year dawn: comparing the United States to the Roman Empire in its so-called decline. It’s a trope as overused as coffee and cynicism, as intellectually lazy as quoting Nietzsche without reading him. And yet, here we are again, in a new year inundated with cries that America… The West—along with democracy, free markets, and everything you enjoyed about brunch Saturday morning—is teetering on the brink of ruin, Fall of Rome-style.

Not only is the comparison between America and Rome’s “fall” wrong, but it’s also boring, unhelpful, and frankly, should be embarrassing for those making it.

Let’s Talk About Rome’s “Fall”

We’ve been conditioned to picture toga-clad senators weeping into their goblets as barbarians torch the Forum. The truth? Few are reading the history. They’re opting for what they picked up along the way in cartoons, movies, and memes. Rome’s fall was less of a cataclysm and more of a slow administrative shuffle. For most regular “Romans” they would have called it progress. For the Byzantines (Romans in the east), Rome didn’t fall at all—the capital moved to a stunning new city called Constantinople and the empire (not a country) carried on innovating, trading, and surviving for another 1,000 years. Their empire stood as a beacon of civilization for over a millennium after the "fall of Rome," influencing art, architecture, law, and religion in ways that endure today. Founded by Emperor Constantine in 330 AD, Constantinople was more than a replacement for Rome the capital; it was a deliberate upgrade. Positioned at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, it became the wealthiest, most fortified, and culturally vibrant city in the world. The Byzantine Empire became the epicenter of Christianity, a shift from the pagan traditions of old Rome. Under Emperor Justinian I (527–565), the empire codified Roman law (Corpus Juris Civilis) and built monumental structures like the Hagia Sophia, a symbol of religious and imperial grandeur. Through Golden Ages, their cultural influence spread through art, religion, and the transmission of classical knowledge to the Islamic world and Western Europe. If Rome had a slogan, it wouldn’t be “Decline and Fall.” It would be “Adapt and Thrive.”

Rome didn’t collapse in a fiery blaze; it transitioned, transformed, and in many ways, progressed. So why do modern cynics cherry-pick this mythical “fall” as their go-to metaphor for the supposed end of America?

The fundamental difference between empires like Rome and countries like Canada or America lies in their purpose, structure, and adaptability. Rome was an expansive, hierarchical system built on conquest, plunder, and centralized authority, where the success of the whole often depended on the might of a single ruler or a small elite. Their economies relied heavily on subjugated labor and territorial acquisition, and their governance lacked the self-correcting mechanisms of modern democracies. By contrast, countries like Canada and America are rooted in ideas of shared sovereignty, the primacy and rights of the individual citizen, democratic participation, and the rule of law, with economies driven by innovation and voluntary cooperation. Unlike empires, they are complex systems designed to adapt, grow, and self-repair, prioritizing individual rights and collective progress over the rigid hierarchies and extractive practices of ancient imperial systems.

Now, I’m almost sure some sour and bitter lefties are going to rage that this describes the patriarchal Nazi fascists ruling Canada but let’s cool our jets. Canada and the U.S. are designed with institutional checks and balances that disperse power and prevent tyranny. The legitimacy of governance is derived from the consent of the governed, not from conquest or hereditary rule. Where Rome openly relied on subjugation and plunder to sustain itself, modern liberal democracies operate on voluntary economic exchange and the rule of law, ensuring that prosperity is built on innovation and participation rather than coercion and control.

The contexts are so radically different—spanning millennia, societal structures, technological advancements, and foundational principles—that any attempt to equate them oversimplifies both history and the complexities of contemporary governance. It’s not just an apples-to-oranges problem; it’s just dumb.

The Problem With the Doom-and-Gloomers

The doom crowd thrives on lazy historical analogies, peddling narratives of inevitability. America, they argue, is Rome 2.0: bloated, corrupt, decadent, destined for the ash heap of history. But let’s call out this nonsense for what it is: shallow thinking dressed up in a Halloween historian’s toga.

Here’s why this comparison doesn’t hold water—or wine, for that matter:

Rome Wasn’t a Democracy:

Rome wasn’t a democracy; it was a republic that morphed into a dictatorship. America is not just a democracy. It’s a stack of democracies from cities, counties, states, and all the branches of the federal government. It is complex beyond imagining with mechanisms for self-correction, even if we occasionally use those mechanisms to elect reality TV stars and various other dummies. It just doesn’t matter. It the system itself that’s important. A complex intellectual machine like no other in history. Like the difference between clay tablets and iPhones different. Rolling through the ages.Economic Dynamism Matters:

Rome relied on slave labor and plunder to fuel its economy. The West, the democracies, and America in particular is an intellectual machine that broke that cycle that had existed through all of history. There is no comparison. Nothing like the time we live in has ever existed. Rome had no middle class - however, you’d like to define it or fret about it. Rome was a brutal and violent military oligarchy supported by a massive and violently victimized underclass. America runs on free markets and innovation; creative energy powered by the same entrepreneurial spirit that makes your favorite food truck possible. Comparing these systems is like equating outer space and the ocean.Technology and Progress:

Rome didn’t have antibiotics, Google, or Beyoncé. More importantly, they didn’t have the foundational change in government, thinking, social science, science, and technology that we call The Industrial Revolution or the Age of Revolution and Enlightenment. America leads the world in technological progress. Anyone comparing America’s trajectory to Rome’s needs to explain why the Romans didn’t think to invent Wi-Fi.

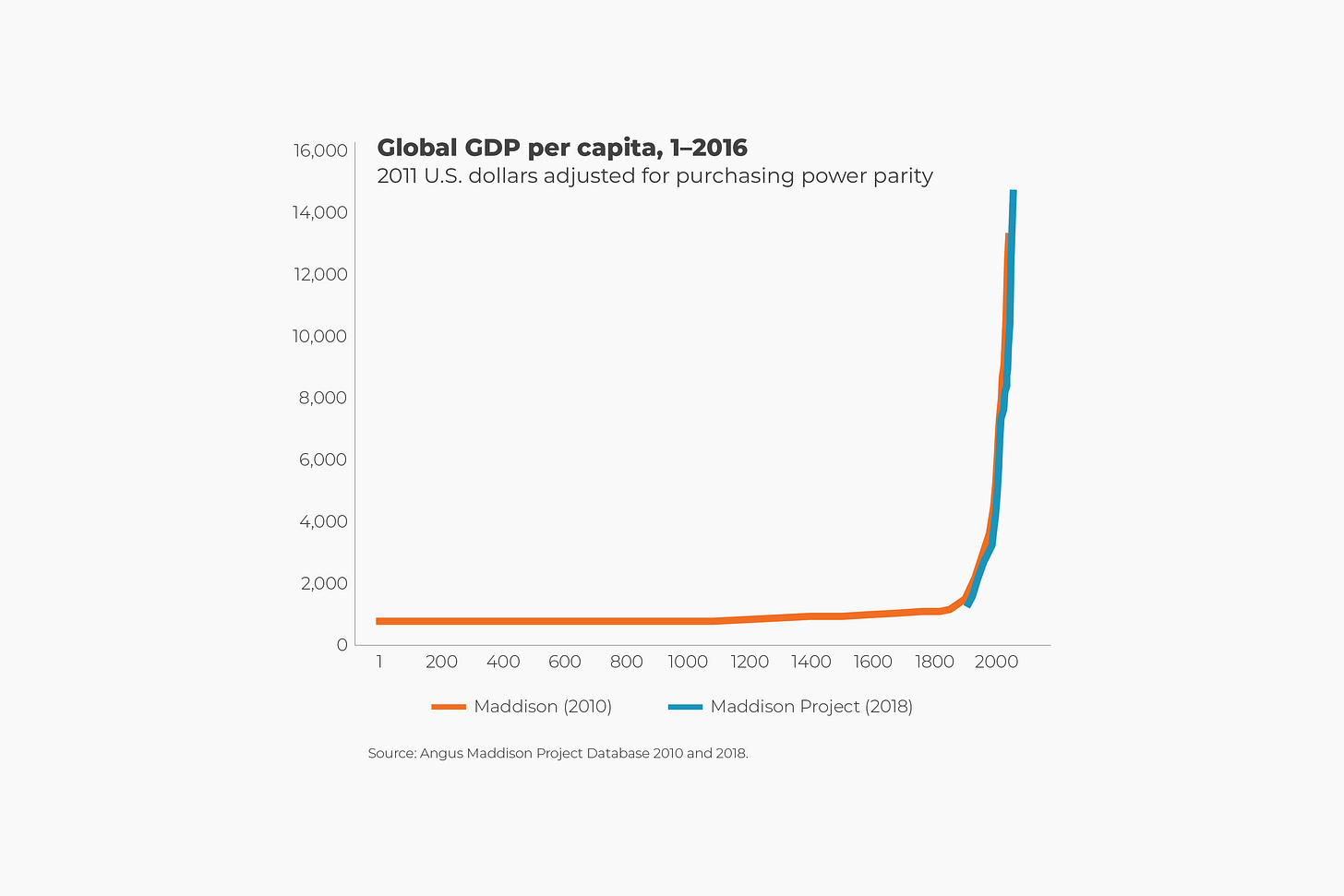

For a visual of this let’s look at a chart of human progress and flourishing from the year 1 of the modern era until today. Notice anything different?

Note the economic growth during the Roman period and the change after its “Fall” in 476.

Economic historian Angus Maddison, at the University of Groningen, spent his adult life estimating gross domestic product (GDP) figures for the world over the past two millennia. According to Maddison’s calculations, the average global income per person per year stood at $800 in year 1 of the Common Era (2011 U.S. dollars). That’s where it remained for the next thousand years. This income stagnation does not mean that economic growth never happened. Growth did occur, but it was low, localized, and episodic. In the end, economic gains always petered out.

All the sour and cynical folks can compare their lifetime of research, analysis, calculation, and collaborative verification to Maddison’s work. Kidding. I’ll state the theme plainly here:

In 1800, average global income stood at roughly $1,140 per person per year. Put differently, over the course of the 18 centuries that separated the birth of Christ and the election of Thomas Jefferson to the U.S. presidency, income rose by about 40 percent.

The advent of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century changed everything. Between 1800 and 1900, GDP per person per year rose from $1,140 to $2,180. In other words, humanity made over twice as much progress in 100 years as it did in the previous 1,800 years.

In 2008, the last year in Maddison’s final estimates, average global income per person per year stood at $13,172. That means that the real standard of living rose by more than tenfold between 1800 and 2008.

Maddison died in 2010, but a group of his colleagues continues his work. The latest edition of the GDP estimates came out in 2018. Although Maddison’s original numbers changed slightly, the long-term trend in income growth remained almost identical. The Maddison Project’s 2018 estimates show that in 1900, GDP per person per year amounted to $2,021 (as opposed to Maddison’s $2,180). By 2016, income had risen to $14,574 per person per year. That amounts to a 621 percent increase since 1900.

Finally, the Maddison Project’s recent estimates show that average global income per person per year rose at a compound annual rate of 1.72 percent between 1900 and 2016. If that trend continues, average global income will reach an inflation-adjusted $60,955 per person per year in 2100 (all figures are in 2011 U.S. dollars).\

Why Cynicism Is Lazy

The problem with doom-and-gloom comparisons is that they’re a cop-out. It’s easier to bemoan the decline of civilization than to acknowledge complexity and work toward solutions. Democracy is messy. Free markets are volatile. Progress is hard. But these systems are also uniquely designed to evolve, adapt, and rise to new challenges—something Rome, with its emperors and static systems, struggled to do at all.

Let’s take a moment to marvel at the sheer cosmic lottery we’ve won by being born in the West, two centuries after the Industrial Revolution—a time and place where the unthinkable luxuries of the past are now mundane realities. We live in an era where clean water flows from taps, diseases that once wiped out civilizations are cured with a pill, and food isn’t just abundant—it’s delivered to our doors with a tap on a screen. Education, freedom, and opportunity surround us, the fruits of centuries of human struggle and ingenuity. We’re not huddled in caves, fearing the night; we’re lighting up cities with electricity and reaching for the stars. No pharaoh, emperor, or medieval king could dream of the comforts we casually enjoy every day. So let’s put the cynicism aside and revel in the fact that we’re alive at the pinnacle of human progress—on the shoulders of giants, in the greatest time and place in history.

A Better Analogy: The Byzantines

If anything, America is more like the Byzantine Empire than Rome in decline: a nation capable of reinvention, thriving under pressure, and innovating in the face of challenges. The Byzantines faced invasions, plagues, and political chaos, yet they adapted and thrived for millennia. In the end, they left the Empiring behind but all the other parts, progress, and families continued on. America has faced its own trials—wars, recessions, social upheavals—and it’s still standing, evolving, and leading.

A Call to Optimism

Cynics like to imagine themselves as modern Cassandras, foreseeing doom while the rest of us scroll Instagram. But pessimism is a self-fulfilling prophecy, and their obsession with decline is a betrayal of the very systems they claim to mourn. Democracy works when people engage with it. Free markets flourish when optimism fuels investment. America thrives when its citizens believe in its promise.

If you really want a historical analogy, consider this: America is less like Rome in decline and more like Rome at its peak—innovative, messy, expansive, and filled with potential. It’s a nation still building, still striving, still learning from its mistakes.

So Let’s Just Stop Mr. Sour, Bitter, And Sad

Next time someone compares America to Rome’s “fall,” hand them a history book. Or better yet, send them to OUR WORLD IN DATA where they can see for themselves what’s really happening. It’s amazing!

Tell them to stop using thousand-year-old metaphors as an excuse for twenty-first-century laziness. Because, as the Byzantines proved, progress isn’t about avoiding challenges; it’s about adapting to them.

America isn’t falling. It’s building, innovating, and—yes—arguing its way toward a better future. Democracy is an argument we have with ourselves about the shape of things to come. It is never settled. And no one should ever wish it to be so. And frankly, that’s a story far more interesting than the one the doom-and-gloomers are trying to sell.

Last comment on this thread, I swear.

So the first thing Trump did, before he gave his inaugural address, was create a way so people could bribe him in office without directly giving him money (which would be illegal). His (and his wife's) cryptocurrency memecoins are a perfect way to send him money, by buying a large amount and forcing the overall price of the coin up, without money ever explicitly changing hands. And he can tell if you did it or not, your digital signature is all over it. What's wrong with this, besides the immorality of it that never would have passed muster with previous Presidents, is that it increases corruption in the US. One of the main reasons that business thrives in the US is relatively low corruption and relatively high transparency. I suppose the silver lining is that he's transparently corrupt.

Second thing he does? Promises to free his "brownshirt" troops from jail where they were languishing for acts of political violence on Jan 6th. People forget that Hitler didn't sweep to power with a huge margin of support, he squeaked in with like 1 vote! It was the ancillary violence and suppression of other parties that really gave him ultimate power. And it's precisely what those other fat-cat tech bros are aiming at too. Trump and the techbros all think they're übermenchen (supermen, in the Ayn Randian/Nietzschian sense of that term). They don't think restrictions, legal, ethical, political, monetary, etc. should be applied to them. It's the ultimate expression of both privilege and toxic masculinity. I'm just going to go in, stomp all over everything until I get what I want and to hell with all the "normies" they don't know what they're doing anyway.

Last thing, he demonizes trans people and promises to deport migrants. They aren't a large demographic anyway so demonizing them doesn't cost him any political capital and they're too few to effectively fight back on their own. Every despot needs an outsider villain just waiting in the wings to eat your babies with their pizza I guess. Or maybe it's pets in this case. The US was built on the backs of migrants and immigrants but worldwide I expect people to get more "locked in" to countries as a reaction to climate change migration. The US also thrived on outsider ideas and new notions. Everyone wants to pretend like we can go back to a golden age. If there's one thing I've learned it's that you can NEVER go back. You can go forward and build a new golden age but you can't return to the one in your memory and you shouldn't try.

So this is what I mean about it being the end of America. And on day one too! Well, at least he's not a time waster. Forget Rome, consider Nazi Germany! It won't be like either one, of course. I just said you can't go back. But it will borrow from some of those features because clichés only exist if they're at least partially true.

Further to my previous comments I suppose I should answer, "what comes after?" I think that's where Cassandra went wrong. Although the main problem is that no one listens to each other. We are, all of us, shouting, "look at me, listen to my wisdom," into the void of the internet and very few, if any, are listening. Maybe we really have nothing new or interesting to say, maybe we're all boring or boorish, maybe everyone else is hiding under the covers furiously thinking to themselves, "Shut up! The monster/alien/crazed killer is around the next corner." I don't know. This whole thing where we monetize pontification and deprioritize conversation and discourse is probably where society as a whole went wrong.

Short Term (0-5 years)

Assuming we do make it through Trump, and I think economic chaos for Canada specifically is entirely likely, we should see an easing of tension and some return to normalcy (whatever that is). After a spat people usually sit down and cooler heads prevail. Alternately, if the fight escalates (possible war between China and the US over Taiwan, trade war with the US escalates under Vance, etc.), we will be in for a long slog. Think nasty divorce with corresponding headaches. We might try to draw closer to Europe or Asia or make new friends in the Caribbean or South America but ultimately, given our joined-at-the-hip proximity to the US we're probably screwed. It'll be the abusive ex that never quite leaves our social circle. Even Canadians will stop being polite but we won't like ourselves for it. Ultimately though none of that financial stuff worries me overly, even if it might be difficult. What worries me is that there is every chance that, just like the previous decades of Gerrymandering and erosion of financial checks and balances there is every chance that Trump and his cronies will take down safeguards and essentially create a kleptocracy or something akin to one, much like Russia has now. This grabbing, grasping monster will destroy many of the freedoms the US currently enjoys, starting with LGBTQ+ and women's rights but definitely not ending there. Crime, including in Canada, will increase, possibly dramatically depending on how successful they are. Science and education are likely to begin to suffer.

Medium Term (5-25 years)

I worry mildly about the crazier scenarios, like Russia invades Nunavut (improve our military!), but more strongly about the more likely ones, like another global pandemic of some sort. Ideally any trade spats with the US should increase our resilience to supply disruptions as by this time we might have greenhouse grown crops of oranges or whatever and might actually be in a decent position (as long as Loblaws and Sobeys are reigned in). Our healthcare system worries me greatly though. 1) We desperately need a way to manufacture our own vaccines and shame on Mulroney for privatizing Connaught Labs. 2) We desperately need to end this shortage of medical care and get things back on track. Canada used to have a great medical system. Privatization, greed and poor planning ruined it for everyone. Poilievre, when he gets in, will ruin it more thoroughly. Although the Bloc Quebecois shows every indication of returning us to leaches and evil vaporous humours before he gets a chance, or at least that's my take from the current state of the health system in Quebec. Fire season is also a medium-sized worry. I'd invest in at least a couple of water bomber planes if I were Nova Scotia. A relatively small investment for relatively big piece of mind. Maybe the Maritimes as a whole could go in on it. Alternately, large fines and no-burn periods are easy and cheap (they might even make money) so do those too. But the big problem will be wind, probably in the form of hurricanes and this will cause both direct property damage and increase the problem of fires. Both drought AND flooding will be big issues. We could use planning around that but given the state of things currently I'm not hopeful anyone will have the time to pull their head out of their ass at the planning departments. I wonder what's so interesting up there? Not really. Adding manufacturing capacity seems like a good thing to do and New Brunswick, at least, seems up to that task. Can we get a good-natured rivalry going?

Long Term (25-100 years)

I'll be dead and I don't care. In the case I'm that I alive then I'll become more and more miserable just like everyone else (get off my lawn!). Sea rise will begin to be a real issue in some low lying communities. So might climate migration. We might begin to not have food unless we grow it ourselves. Coffee might not be a thing, nor chocolate (kill me now). The farther fetched: I will NOT run around for an entire movie while being chased by killer robots. I give up as long as it's quick. If it's more "Matrix-y" then I'll do myself in. No one wants to be a battery when they grow up and I suck at video games anyway. I would, however, gladly join the new "Culture" (Ian Banks) if that lovely scenario happens. I hope it does. Do I think it's likely? Well, Moore's "Law" has proven correct and it's exponential in nature so I suppose it's plausible but I'd really give more like 1 chance in 10, although Kurzweil says it's 2050 for The Singularity. Honestly, no idea when but likely to happen eventually if infrastructure survives to any extent. I might need some post-apocalyptic metal and bone outfits a la Mad Max if the robots take over employment though. It's likely to be "none of the above" for those scenarios though. It'll probably more like the end of "Her" where the bots all chose to ignore us because they have more scintillating things to pay attention to. Just like real kids do to parents today.

Why do I insist on being pessimistic? Well, I've watched market bubbles before. I've lost money in them, so have friends. I've heard the constant refrain of boosters saying things like, "it'll never end!" then watched as people were let go en masse or lost their house. If nothing else things do not feel balanced. Equilibrium is where we have peace and prosperity. I don't feel like we have equilibrium or are even headed towards it. Sure, disequilibrium is where you get the most profit, but also the most pain.