The Real Secret To Buying Canadian

On Pickup Trucks, Great Canadian Sports Cars, and the Greatest Canadian Mustard Company Ever. The easiest and quickest way to get the most Canadian bang for our bucks, er, loonies.

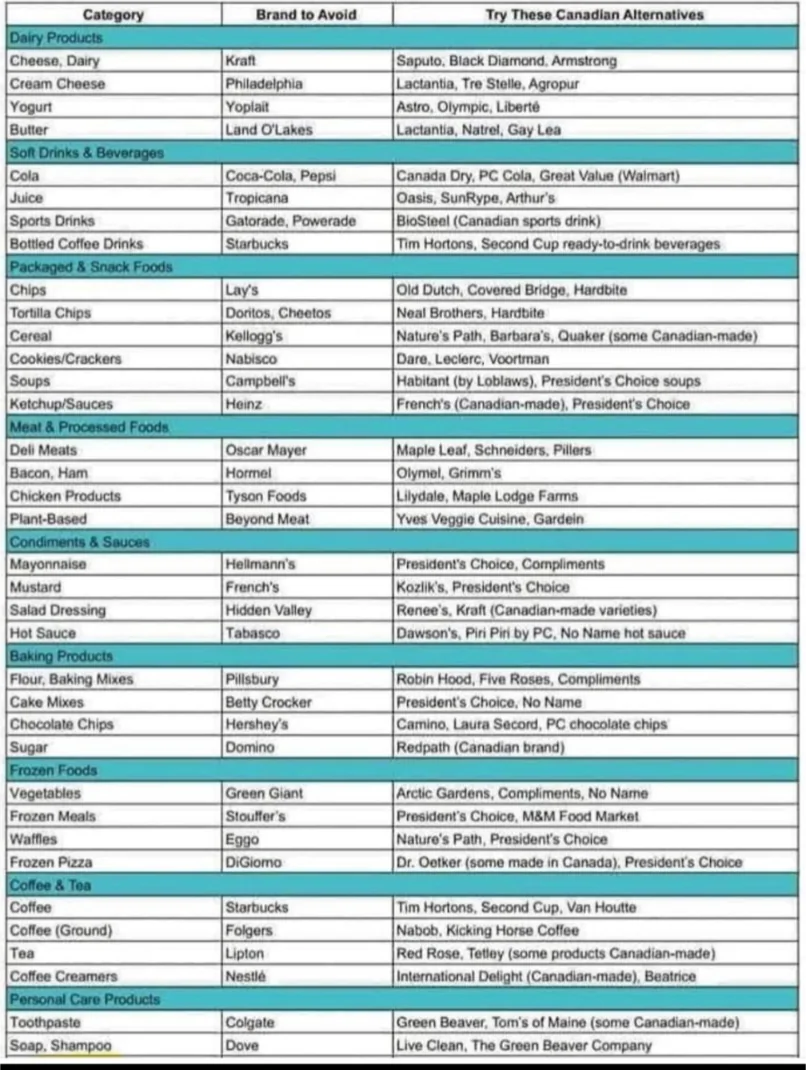

If you’re on social media or following the news since Trump startled Canada with talk of tariffs, you’ve probably seen something like this. Newly minted economically patriotic Canadians sharing ways to “fight” Trump and “push back” against tariffs by buying Canadian.

People are even launching Buy Canadian apps to help consumers find Canadian options in the grocery store.

CTV helpfully reported this week, if the product is not made in Canada, but the shopper wants to only buy Canadian, the app will provide a list of alternatives.

For example, if the user were to search for Pringles potato chips, which are produced by American company Kelloggs, it will suggest Canadian brands such as Old Dutch or Humpty Dumpty. The app says, “these brands provide a range of snack options that support the Canadian economy.”

And if that’s not enough “Cantreprenuers” like Daniel Naraine, who built his grocery store, with a simple mission: to support local food entrepreneurs, are popping up online all over the country.

Since launching in 2021, the Toronto-based ‘City Cottage Market’ on Kingston Road near Birchmount Road has focused on stocking homegrown, Canadian-made products to help small businesses thrive.

Ya! Buy Canadian, Bye Trump!

This in-depth CBC episode of THE CURRENT really captures the mood in Canada. We have all come together and showed up for this. We’re really committed to buying Canadian.

This is Great!!!

BUT…

In Nova Scotia, the idea of buying local has captured the public imagination, and for good reason. People are sharing their favorite homegrown products—wine, mustard, and countless other items—to celebrate our province’s unique offerings. Yet there remains a glaring mismatch between these conversations and the more significant factors that truly drive money out of our region. As important as it may be to support local businesses, if we genuinely care about building a resilient local economy, the focus must shift into high gear and focus on transportation.

If you really want to make a difference. If you really want to show Trump and support Canada there’s one change you could make that would make all the difference… and Trump very well knows it. The truth is, he’s scared to death of it. He’s ready to bow down and make all kinds of special allowances for it.

All of our food, clothing, and other expenses together don’t add up to this one expense.

What is it?

Well, next to your home, which seems obviously Canadian (even though the truth is a little more complicated) it is, not surprisingly, the biggest thing you own.

It’s out in the driveway. Or more likely, they are out in the driveway.

In fact, there are 26.4 million SUVs, trucks, and cars registered in Canada.

Transportation accounts for about 25% of the average household spending. The more educated, urban, and well-off we are, the more we spend on transportation.

This compares to a little over 30% for shelter and 15% for food.

You can see the Statscan numbers here.

Note: These are 2019 numbers. The surveys are only done every 2 years. The 2021 numbers are all messed up because of COVID, and the 2023 numbers aren’t final yet. However, it is fair to assume the cost of transportation and all things did not go down and the proportions are about the same. More of us are moving ever closer to two cars per household...

Here’s how it breaks down per car.

Buy Canadian Cars?

In 2023, Canada's automotive industry produced approximately 1.55 million vehicles, marking an increase from 1.23 million units in 2022.

This production includes various types of vehicles, such as passenger cars, light commercial vehicles, and heavy trucks. For instance, in 2023, the industry produced about 1,159,000 light commercial vehicles (what the system calls our SUVs and Pickup Trucks to help them skirt our own rules for environmental limits), nearly 377,000 passenger vehicles, and approximately 17,530 heavy trucks.

It's important to note that Canada's vehicle production has experienced fluctuations over the years all outside the control of anything Canada, the workers, or the government can do. The peak production was in 1999, with over 3 million vehicles built. The end of the Auto Pact in 2001 and the implementation of new trade agreements altered the competitive landscape, influencing automakers' decisions on where to allocate production. The lowest point was in 2021 (COVID), with around 1.1 million units.

The automotive sector remains a significant part of Canada's economy, accounting for 10% of manufacturing GDP and 23% of manufacturing trade. The industry directly employs more than 125,000 people in vehicle assembly and auto parts manufacturing.

While Canada does have an automotive manufacturing sector, the reality is that it functions as an extension of the larger North American and global auto industry rather than an independent, self-contained system. The argument that purchasing a vehicle in Canada supports the Canadian economy is only valid in a very limited sense—mostly in terms of labor and some supply chain activity. But in the grand scheme, the money still overwhelmingly flows out of the country.

The majority of vehicles on Canadian roads are either imported entirely or assembled in Canada using parts that are mostly manufactured elsewhere. Even vehicles assembled in Ontario, for example, are built within a framework dictated by American and international automakers. The factories might employ Canadians, but they are owned by U.S. and multinational corporations, and the profits are directed accordingly.

When it comes to auto parts, Canada does have a substantial industry, with companies like Magna International playing a major role in supplying components globally. However, the ultimate decisions about production, pricing, and supply chains are made in boardrooms outside of Canada. The vast majority of the intellectual property, design, and high-value decision-making resides with the parent companies in the U.S., Japan, Germany, or elsewhere.

Perhaps the best argument for calling any of this "buying Canadian" is that it employs Canadians. The assembly plants, parts manufacturers, dealerships, and service industries all contribute to local jobs. But if we're looking at ownership, profit retention, and capital flow, the auto industry is anything but Canadian. The money from vehicle purchases doesn’t stay here in any meaningful way. And we would employ a lot more and more securely if we met our own transportation needs with our own steel and our own ideas and designs. It’s a fast food, high-calorie version of a real domestic industry.

A truly Canadian transportation system would involve domestic ownership of production, financing, and infrastructure—not just assembly plants that are part of foreign supply chains. Until that exists, calling vehicle purchases “buying Canadian” is, at best, economic bullshit.

Why Don’t We Make Our Own Cars? Or Even Snowmobiles?

Why aren’t cars made in Canada? Or motorcycles? Or bicycles? Or even snowmobiles, for goodness' sake? Well, hurray, we do make some Ski-Doos, sort of. It seems like a weird oversight for a country that spends so much time in motion—crisscrossing vast landscapes, commuting absurd distances, hurtling across frozen lakes at speeds that defy common sense. We are a nation practically built on moving things from Point A to Point B, yet when it comes to making the machines that do the moving, we’re oddly absent.

The headquarters, the patents, the executive bonuses, the serious money? That’s not Canada.

Which is sort of embarrassing when you think about it. This is a country that invented the snowmobile. The Ski-Doo! A machine that literally redefined how Canadians get out and enjoy the winter. But even that—the most Canadian form of transportation imaginable—is now produced by a company that long ago took its operations global and only has one factory left in Canada. We do not build our own bicycles, or our own motorcycles, or—any other transportation system you can imagine. Yes, I love walking the old rail trails as much as anyone, but we can all agree from Canada Day One to today we needed to make that railway work.

And yet, we buy those pickup trucks. Oh, do we buy them! By the millions, pouring billions of dollars into an industry that treats us as a market, not a manufacturer. Every month, a typical Canadian family shells out more for transportation than for food, which is an astonishing fact when you consider that food is the thing that prevents us from dying, and transportation is mostly about sitting in traffic so that we can get the money to buy the food. But almost none of that money stays in Canada. The dealerships collect their cut, which is now getting close to a ‘pay to play’ deal and they have to make their money on parts and service. The mechanics, now little more than computer printout readers, get paid, but the real wealth—the capital, the ownership, the control—flows outward, frictionless, and automatic.

So we are a nation of drivers who do not make the things we drive. A country that prides itself on its independence but outsources all of its most fundamental conveyances of that freedom.

If we truly want a self-sufficient and prosperous Canada, we need to build and control our own means of getting around—whether that means manufacturing vehicles, investing in sustainable public transit, building communities that don’t need so many cars, or rethinking how we move goods and people across this enormous land. Once we secure transportation under our own terms, everything else follows. Then, whether we choose to buy imported luxury oranges or stream international entertainment, those become personal choices—not structural leaks draining wealth from our economy.

If we were serious about local economies, if we were serious about self-sufficiency, we wouldn’t just be arguing about where our mustard comes from—we’d be asking why we don’t make our own damn cars.

It takes a lot to change the culture

The first time a young lobster fisherman from Barrington, Nova Scotia makes real money—REAL money, not just the scraps from crewing on someone else’s boat but his own first season’s catch—he knows exactly where he’s going before the first cheque even clears. Not to a bank. Not to an investment advisor. Not even to his mother’s house to drop off a stack of crisp hundreds like a good son should. No, he’s going straight to the Dodge dealership. Clare Dodge Chrysler Limited in Weymouth, Nova Scotia has an astonishing 100 new and used RAMs in stock to choose from. But over in the showroom at Smith & Watt Chrysler in Barrington Passage, they have what he really wants, a murdered out 3500 with stepsides and duallies.

He doesn’t even hesitate. He walks in like he owns the place, still wearing his rubber boots and a hoodie that smells like salt and bait. He could haggle, maybe, but that’s not the point. The point is to make it as simple as possible for the salesman to tell him the number—the biggest number he qualifies for, the most loan they’ll give him, the absolute maximum he can sign his name to without someone in the back office shaking their head. He doesn’t even pretend to consider a 1500. That’s a truck for schoolteachers and grocery-getters. He’s looking at a 2500, at least. Maybe the Cummins diesel if he can stretch it. A Power Wagon if he’s feeling cocky.

Superbowl advertisement from yesterday - This is what we’re up against in the dominant cultural narrative, the American auto industry version of the story.

Does he need this truck? Absolutely not. It will never tow a single backhoe, never haul a single load of gravel. It will spend 90% of its time parked outside the Tim’s, burning through diesel and testosterone in equal measure. But that’s not the point. The point is that when he rolls up next to his buddies, he’s not the one getting laughed at but when he rolls up the rim he’s secretly praying to be saved from the economic chains of his enslavement in a strange land of payments, fuel bills, and dealer scheduled maintenance. A smaller truck would make him look like a small cat, like a guy who’s still waiting to see if this fishing thing is going to work out. No, he’s all in now. Fully committed.

And for the next few years, he’ll be on that high—driving around like a king, feeling that perfect mix of pride and regret that only comes with monthly payments the size of a lottery win. He’ll buy the rims, the light bar, the exhaust tip that makes it sound like a 70’s muscle car with the air cleaner taken off. He won’t think about what happens when the body - his or the truck’s - gives out, when his hands get too stiff to tie a knot in the cold, when the mornings get too hard and the old rocking chair starts looking tempting.

Because today, he’s 22 years old. And today, he’s got a truck.

But why? Why don’t we make a Canadian truck? Or better, offer some alternatives, and an alternative vision and goal for the young lobsterman to dream of?

The short answer is: history, money, and the Great American Smothering Hug.

The long answer starts with the fact that, once upon a time, Canada did make cars. Real, actual, roll-off-the-line-here vehicles with maple-scented optimism. In the early 20th century, companies like McLaughlin, Russell, and Bricklin (ah yes, the Bricklin, famous for its gullwing doors and complete lack of commercial success) all took a stab at making distinctly Canadian automobiles. But then came the American behemoths—Ford, GM, Chrysler—who, with their titanic economies of scale and smooth-talking trade negotiators, convinced Canada to abandon the dream of a national auto industry in exchange for jobs in American-owned factories. This culminated in the Auto Pact of 1965, which effectively made us the northern assembly line of Detroit.

It was a great deal if you wanted jobs. It was a terrible deal if you wanted an actual Canadian car company and an independent economy.

Since then, our manufacturing capacity has been surgically attached to the global auto industry, meaning we don’t design cars, we don’t own car companies, and we certainly don’t decide what gets built. Instead, we take orders from head offices in Michigan, Germany, and Japan. And when they decide to close a factory? Too bad, so sad, the market has spoken.

But it’s not just cars. Why don’t we make motorcycles? Because Harley, Honda, and Ducati already have the market locked down, and developing a new brand from scratch requires a burning pile of cash and some reckless optimism. Why don’t we make bicycles? Because, ironically, even though Canada is a nation of cyclists (half of whom are trying to dodge potholes the size of hot tubs), the manufacturing has all been offshored to Asia where labor is cheaper. And snowmobiles? Well, we do have Bombardier… or at least, we did, before they sold off most of their transportation divisions. Now, BRP makes Ski-Doos, which is something, but it’s a small part of a globalized multinational enterprise.

And that’s the core problem. Every time Canada gets close to building its own transportation ecosystem, it either gets swallowed by an international conglomerate or buried under a mountain of foreign competition. Meanwhile, we continue shipping out raw materials—steel, aluminum, lithium—so that other countries can build things and sell them back to us at a markup. They call that Capitalism. And we should be in on it instead of selling off commoditized raw materials like a bunch of feudal serfs.

Which is why, if we actually care about being independent, about having a transportation system that isn’t just an extension of America, we need to rethink everything. Cars? Sure. Trains? Definitely. Electric bikes? Absolutely. But if we don’t start owning the process—if we don’t build the main things we use every day, the thing we spend the most money on—we’ll always be passengers in an economy driven by someone else.

Wait… I don’t want to end there

I’ll leave you filled with hope, desire, and seething frustration.

What if I told you that there was actually a successful Canadian car company? That it has been around since the 1960’s and is now a second-generation family-owned company that makes some of the most sought-after, beautiful, and prestigious cars in the world? And the Canadian government does everything they can to make life miserable for them.

Here’s the whole story from Hagerty.

And what if I told you that the only catch was that you can’t easily buy one because, though they are common on the road from California to Switzerland, they are not allowed to be distributed in Canada?

Why?

Unbelievably, the problem is bureaucratic, arbitrary, and patently unfair rules that are designed to make it so no one, especially family-owned local companies, no matter how globally successful, can even think of competing with the global auto industrial complex that has the power to bring Trump to heel, and makes an economic fool out of you and me as we search the grocery shelves and try to remember the name of the greatest Canadian mustard company ever.

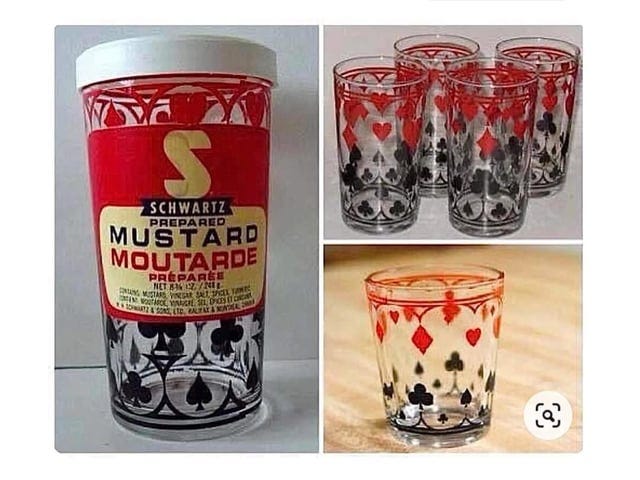

The answer should be Shwartz Mustard. Schwartz, the company was founded in 1841 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, by William Henry Schwartz. Initially focusing on coffee, the company expanded into spices and, by the 1950s, began selling prepared yellow mustard. Schwartz's mustard became a household staple in Nova Scotia and was known for its distinctive packaging in reusable glasses adorned with card suit symbols. However, in 1984, McCormick & Company acquired the Schwartz brand, and its operations have since been integrated into the larger McCormick portfolio.

Anyway, I’ve had the pleasure to visit the Intermeccania factory and see their cars being made. It’s a true thing of beauty. But I’m a little late to share this. In the last few months the Reislet family sold the company to a Calfornia EV startup in return for a 20% interest in that company. I guess two generations of fighting the Canadian government/industrial automobile complex was all they had in them. It’s sad. I hope you get to drive one someday. Or at least find a perfect Shwartz Mustard glass at the local vintage shop.

Have a great week!

The global supply chain (for most things) is outta control, finessed by the financial sector (leasing, insurance); the profits are in the trucks and SUVs so they actually try not to sell cars. I read this in a car industry mag some years back. Canada has fallen for this big time; trucks are a status symbol designed not to be repairable; thanks Steve Jobs for the concept. As for global warming...