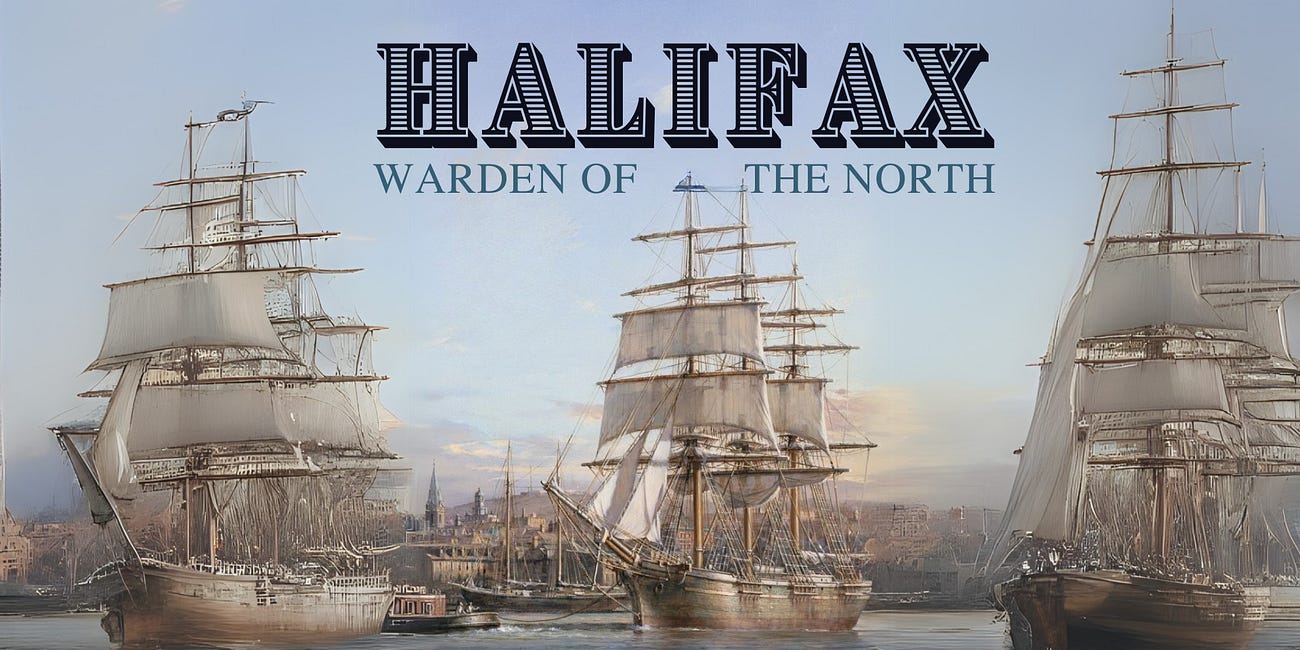

The Poorest Place in North America (And Why It Stays That Way)

Most people assume it’s bad luck or geography. The truth is much more uncomfortable.

Wednesday evening. Just getting Dorothy to bed. My brother texts me and starts a thread of conversation that goes on until after midnight… about economics.

What he ultimately wanted to know is, if that’s even close to true… where does it leave Nova Scotia? Is Nova Scotia the poorest place in North America?

The short answer is yes.

And if you’re busy or uncurious you can stop here with reasonable confidence. But regular readers of THE BEE know there’s another five thousand words ahead, divided up into smaller stories filled with facts and different ways of looking at things that both complexify and clarify the subject at hand.

By the numbers, by GDP per capita, Nova Scotia ranks dead last among all provinces, states, and territories in the US and Canada. But that’s just the surface of the story. It’s easy to blame geography, history, or bad luck, but the truth is more uncomfortable: Nova Scotia’s institutions—its economic structure, political systems, and business environment—are designed in a way that ensures stagnation.

In this series of posts over the next few weeks, Why Provinces Fail will explore how extractive policies, capital flight, a hostility to local private industry, and a culture of bureaucratic dependence have left Nova Scotia trapped in a cycle of underperformance. In future installments we’ll explore how Nova Scotia went from first to last in Canada, what we can learn from our most Southern North American neighbour - Mexico, review the book Why Nations Fail, and do the work to understand the surprisingly small workforce who does the wealth-creating work.

Where other economic boosters might explore what the best economies of the world are doing - Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, Singapore’s financial mecca, Germany and Japan’s industrial revolution - in THE BEE we’ll explore the idea that there's more to learn from the other failures. We're doing so bad it's not about tweaking our way through the top ten, it's about stopping doing what the “stuck” economies are doing and learning to stop making the mistakes of the worst economies in the world.

FIVE FACTS ABOUT GLOBAL POVERTY THAT MAY SEEM UNCOMFORTABLY FAMILIAR

A new polarisation is emerging within the developing world between ‘moving’ and ‘stuck’ countries.

The global poverty headcount depends on how it’s measured.

The world’s poor are rural but not necessarily farmers.

Three-quarters – or 1 billion – of the world’s poorest live in fast-growing developing countries. Growth is not solving the problem of poverty and is in many places making it worse.

More than half of global poverty is found in countries that are deindustrializing with fewer manufacturing jobs in the face of liberalizing trade and as new multinational competitors enter global value chains.

https://oecd-development-matters.org/2019/03/14/5-facts-about-global-poverty-that-may-surprise-you/

Robert works at big building sites. He’s a construction carpenter on those big “urban and up” high rises you see going up from Larry Uteck to Robie Street and all across Dartmouth. He’s a carpenter and spent his early years working concrete carpentry. He and I are about the same age - he’s a little more than a year younger. We were brought up pretty much as twins. We look alike. Same size, strength, and same brain. I started my working life in the same job until fate intervened in an extreme fashion - a story for another day. But just to say I get what he does and I know how weird the work is.

Carpentry is unique among the trades in that it often demands on-the-spot improvisation in a way that plumbing, electrical, or roofing rarely do. Those trades operate within strict codes and standardized methods—pipes must connect, circuits must flow, roofs must seal—with little room for deviation. But carpentry? Carpentry is a conversation with chaos. Wood swells, walls lean, angles deceive, and measurements—no matter how precise—sometimes just don’t work in the real world the way they did on the blueprint. A carpenter, often the lowest-paid trade on the site, is part builder, part problem-solver, part artist. While an electrician is testing a circuit, a carpenter is staring at a stubborn joint, head tilted, measuring tape out, muttering curses at gravity itself. It’s a trade that rewards adaptability because no two projects are ever exactly the same. The best carpenters aren’t just skilled—they’re thinkers, fixers of the unexpected, masters of making things work when they really, really don’t want to.

On these job sites, there are also people who are seemingly hired only from the neck down. They have time to talk and grumble and toss ideas around about the world and how it works. So from race cars to racism and BBQ to babies, you hear a lot of ideas. You may not be surprised to learn that there are a lot of geopolitical economics experts working on these job sites too, with big ideas about how to fix all the problems of the world as easily as a misaligned door frame.

Their solutions usually involve a few forceful kicks, a bigger hammer, or just declaring the whole thing someone else’s fault. You’ll hear that interest rates are a scam, that the government should run like a household budget, and that if they were in charge, things would be simple. There’s always a guy who “could’ve been a millionaire” if not for taxes, another who swears gold is the only real money, and at least one who has a bulletproof plan to fix the housing crisis—but nobody’s listening. It’s democracy in its rawest form: half-informed, overconfident, and delivered with the certainty of a man holding a nail gun.

The thing is, they’re not entirely wrong. Stripped of policy nuance and economic jargon, their ideas often circle around real problems: things cost too much, wages aren’t keeping up, politicians are out of touch, and the people doing the actual work of the world keep getting squeezed. And so, between framing walls and pouring concrete, they build their own economic theories too—rough around the edges, a little uneven, but solid enough to hold up under the weight of another long day.

So it’s not unusual for my brother, after an evening chewing on something he was trying to ignore all day, to call me to talk about some detail of world affairs heard yelled through some half-built wall. The questions eventually got down to talking about what is poor and how is wealth measured?

How is Wealth Measured?

I write about this often. In modern government and media, wealth is measured by GDP - Gross Domestic Product.

GDP SIDEBAR:

(SKIP IT IF YOU’VE HEARD THIS ONE BEFORE)

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – A Recap

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the total monetary value of all final goods and services produced within a country (or province) over a specific period, usually a year. It is the most common measure of economic activity and national wealth.

Key Components of GDP

GDP is typically calculated using the expenditure approach, which breaks it down into four major categories:

Consumption (C):

Everything households spend money on—food, rent, healthcare, entertainment, etc.

Usually the largest part of GDP in developed economies.

Investment (I):

Money spent on new businesses, factories, machinery, housing, and infrastructure.

This includes corporate investments and government spending on public works.

Government Spending (G):

All public sector expenditures—salaries of government employees, military, healthcare, schools, infrastructure projects, etc.

Does not include transfer payments (like welfare or pensions) because they don’t directly produce goods or services.

Net Exports (Exports - Imports) (X - M):

The value of goods and services a country sells to other countries (exports) minus what it buys from abroad (imports).

A country with more exports than imports has a trade surplus (boosting GDP). A country with more imports has a trade deficit (reducing GDP).

The GDP formula:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

GDP Is Used Talk About:

Measures of economic growth—Is the economy expanding or contracting?

Indicates the standard of living—A higher GDP per capita (GDP divided by population) usually means a wealthier country.

Guides policy decisions—Governments and central banks use GDP trends to shape taxation, spending, and interest rate policies.

Compares economies—GDP allows us to compare economic strength between countries or provinces.

Limits of GDP

GDP is useful, but it doesn’t measure everything. It doesn’t account for inequality—A rising GDP doesn’t mean everyone benefits equally. It ignores informal economies—Unreported work (cash jobs, black markets) isn’t counted. It does not measure quality of life—It counts military spending and medical bills, but not happiness or well-being. It overvalues consumption—Buying more cars and phones boosts GDP, but it doesn’t mean the economy is producing real long-term wealth.

Per Person

But GDP is divided up among the total population, so even if you accept this measure it makes sense to divide it by the number of people. GDP/Population - GDP per person, or GDP “per Capita” because saying per person would be far too simple and understandable. Economists, policymakers, and academics prefer per capita—Latin for “per head”—because nothing says “I’m smarter than you” like dropping a little dead language into everyday conversation.

Job Site Economics - By The Numbers

Let’s just start by the numbers to see where Robert’s workplace economists got their ideas and then dive deep into the Whataboutery that always makes economics less of a science and more like a late-night kitchen table fight between drunk uncles at Christmas.

Having spent about equal time on Nova Scotia job sites and at the London School of Economics and other universities I can share this: The difference in observations and insight is less than you would think. At LSE they like to call economics a social science—because calling it a real science would invite uncomfortable scrutiny.

Basically, calling economics a social science allows its practitioners to sound authoritative while keeping the escape hatch wide open. It’s part math, part storytelling, part political philosophy—wrapped in enough jargon to ensure that, no matter what happens, the economist is never actually wrong. It’s pretty much the same on the construction site. You’re sitting on a stack of drywall at break, and suddenly, the guy who can’t find his own hammer is explaining how the Bank of Canada is ruining everything.

At the London School of Economics (LSE), economics is traditionally defined following the perspective of Lionel Robbins, a prominent LSE professor. In his seminal work, An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science (1932), Robbins defined economics as:

"the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses."

Here’s my personal definition of economics. It’s the story we tell ourselves about where our wealth comes from and where it goes. In this definition, it’s the word story that does the heavy lifting in the Joseph Campbell Hero’s Journey sense.

Let’s Look At Those Numbers

Canadian GDP Per Capita by province in Canadian dollars

This table is the most recent government of Canada stats as posted on Wikipedia, which is a good table because it can be reordered by pressing any of the headings.

Sure enough, Nova Scotia has the lowest GDP per capita in Canada.

It’s a consistent trend. And even within Nova Scotia, the GDP per capita has not materially changed over the last 10 years. As Nova Scotia’s Office of Economics and Statistics reports, “With the pandemic and recent population growth, real GDP per capita has declined or showed muted growth in most provinces.”

But how does that look compared to the US?

Here are the five poorest states. Converting Nova Scotia to USD, we get a depressing: $42,500. That’s compared to $53,061 in Mississippi.

So Nova Scotia is not only the poorest province, in the poorest region - The Maritimes - where it competes with New Brunswick and PEI for last place, it’s by a wide margin the poorest when compared to any state.

What about my brother’s opening question? Is the richest province poorer than the poorest state? Well, cold comfort, it’s not that bad. Alberta, at about $72,500 USD is mid-pack among US states not far from Florida and Arizona.

This is Where The Story Begins

So where does that leave us? The numbers don’t lie—Nova Scotia is the poorest province in Canada and the US by GDP per capita. But if you’ve made it this far, you already know that numbers alone don’t explain everything. They don’t capture the hidden wealth in skills, community, and ingenuity. They don’t tell the full story of why some places rise while others stay stuck. And most importantly, they don’t reveal what Nova Scotia keeps getting wrong—or what it could start doing right. With that in mind, we’re going to compare Nova Scotia to Mexico.

In the next few posts, we’ll go deeper: into the myths we tell ourselves, the policies that keep us stagnant, and the hard lessons from economies that broke free from their traps. Because understanding why we’re last is just the beginning—figuring out how to climb out is the real story.

PART TWO:

What Sank Nova Scotia’s Economy? A Forensic Look at the Turning Points

THIS IS THE SECOND IN A SERIES OF POSTS ABOUT WHY NATIONS (AND PROVINCES) FAIL

Where is Mexico?

Meet the axolotl - pronounced ACK-suh-LAH-tuhl (in English), though every eight-year-old girl in Nova Scotia already knows that. They can also tell you it lives in only one place in the wild: Lake Xochimilco, just outside Mexico City. Don’t worry if you’ve never heard of it - if you’re over the age of twelve and not currently obsessed with glittery amph…

I am fascinated by this story and look forward to the follow-up. I also love talking about economics.

One thing is certain: GDP is a poor indicator of quality of life!

As a recent newcomer to the province I have found that the quality of life here is amazing. There is a sense of community here you don’t see in other parts of Canada in my experience. For example, the local fire hall had a St. Patrick’s Day “concert” that was really an excuse for folks to bring their instruments out to a gathering and play for each other. Cost? $5, and there were sandwiches and donuts!

I have also noticed there is a vibrant cash economy here that isn’t reflected in the data. People here are happy, and happy to be here!

haiti is the poorest place in north america and by extension the western hemisphere