The Missing Middle: Why It’s Time to Imagine a new Federal Progressive Conservative Party

Canadians are exhausted, embarrassed and existentially threatened by politics that feels like a shouting contest. It’s time to talk about the centre again.

This is surely the Conservative Party of Canada’s swan song.

After two decades of drifting further from its founding promise—a big-tent coalition that could unite the right and govern the country—it now faces the real possibility of losing everything, and fast. And they can’t imagine the ghost of Justin Trudeau is going to haunt the hall of parliament to save them.

The warning signs are no longer subtle. A populist pivot has alienated moderates. An endless parade of great pretenders including leaders—Harper, Scheer, O’Toole, and now Poilievre—have each tried and failed to strike the right tone. One by one, they offered Canadians variations on the same theme: fiscal conservatism wrapped in culture war bristles, long on rhetoric, short on substance. And, to be plain spoken… it just hasn’t been interesting. Each campaign became a referendum not on the Liberals, but on the CPC's ability to seem palatable, competent, or even Canadian in spirit.

Now, twenty years in, what once looked like a strategic merger seems more like a failed arranged marriage - two mismatched traditions forced together, held up by inertia, and slowly crumbling under the weight of their contradictions.

If they lose this much this fast after offering so little for so long, it won't just be another defeat. It will be the final chapter in a political experiment that never quite found its soul.

Even in politics, there’s no use in sticking with your mistakes just because they cost a lot of money and you spent a long time making them.

The Progressive Conservative

The old federal Progressive Conservatives - Stanfield’s party - weren’t perfect, but they held the centre with a kind of steady, boots-on-the-ground pragmatism. They spoke to people who wanted good government, not big government. They wanted change as much as the next person, but at a pace that everyone could understand and only with good well-understood reason. To citizens who believed in free enterprise, personal responsibility, and a sense of duty, but didn’t feel the need to wage culture wars or burn the house down to make a point.

That kind of political home no longer exists federally.

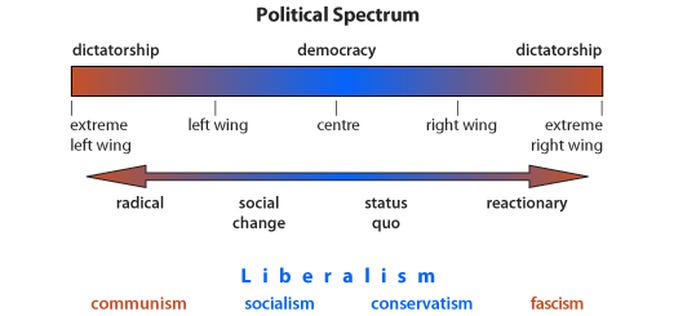

Today’s CPC has veered increasingly into American-style populism - obsessed with wedge issues, grievance politics, and owning the libs. The Liberals, meanwhile, have drifted further left, chasing identity politics, bureaucratic bloat, and central planning fantasies. The NDP clings to the left bank, leaving no viable space for moderation, common sense, or centre-right principles grounded in reality.

But out in the provinces, something interesting has endured.

Six provincial Progressive Conservative parties—in Ontario, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland & Labrador, Nova Scotia, and PEI—still operate, still win elections, and still govern with a brand of conservatism that feels... Canadian. Less theatrical. More practical. These parties have never merged with the CPC. They exist in parallel, often governing while Ottawa flounders.

So here's the question: what if they came together?

A New Federal Progressive Conservative Party

What if the old Progressive Conservative movement was reborn at the federal level—not as a nostalgia act, but as a serious alternative for the millions of Canadians who no longer see themselves in the increasingly tribal world of red versus blue?

A new Progressive Conservative Party of Canada—grounded in fiscal responsibility, regional representation, and a classically Canadian sense of balance—could offer voters something they haven’t had in decades: a true political centre. Sane, serious leadership for a country that’s been drifting off course.

It would appeal to blue Liberals, red Tories, and farm green on all sides. It would speak to the Maritimes, the suburbs, and the West without preaching or pandering. It could draw disillusioned centrists out of their political exile. And most importantly, it would give Canadians something they’re desperately missing: a way forward that doesn’t require choosing between extreme ideology and insanity.

Twenty years in, the CPC experiment looks more like a failed merger than a lasting solution. Maybe it’s time to try something else. Or rather—something older. Something wiser. Something that once worked, and could again.

A party that intentionally offers Canadians the centre again?

That’s not just a political strategy. That’s a public service.

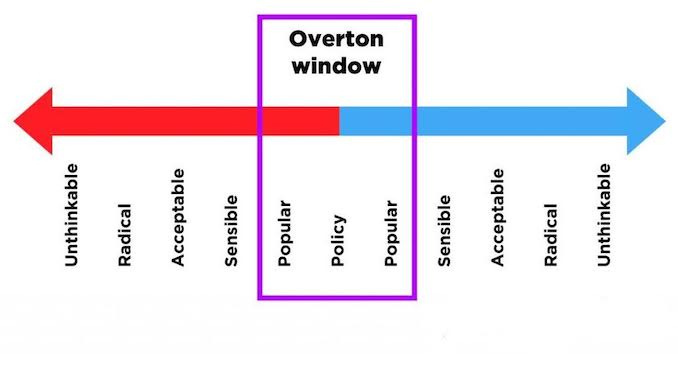

Looking Through the Overton Window

In political theory, the Overton Window refers to the range of ideas and policies that the public considers acceptable or mainstream at any given time. Ideas outside the window are seen as too radical, too regressive, or just plain unrealistic. Politicians and parties that stay inside the window are more likely to gain broad support; those who operate outside it are often dismissed as fringe or dangerous—at least until the window shifts.

And it does shift. Sometimes dramatically.

In Canada, the view from the Overton Window has changed noticeably in recent years. On the left, policies once seen as radical—like guaranteed income, expansive identity politics, and federal climate micromanagement—are now party platforms. On the right, populist rhetoric, anti-institutional sentiment, and conspiratorial noise have crept into mainstream conservative discourse. Voters are left choosing between parties that increasingly feel like they're arguing from the edges of political sanity.

This is where a new federal Progressive Conservative party could step in—not as a radical option, but as a return to the viable middle, well within the boundaries of the Overton Window.

It would offer:

Fiscal responsibility without austerity.

Environmental stewardship without eco-theocracy.

Respect for tradition without moral panic.

Social compassion without bloated bureaucracy.

National unity without cultural erasure.

In other words, it would sound like something Canadians could actually live with.

For voters, this means having a choice that doesn’t force them to hold their nose, vote strategically, or choose between extremes. It would re-anchor the Overton Window toward reason, drawing support from blue Liberals, red Tories, disaffected centrists, and the politically homeless—people who feel Canada has become a place of ideological shouting rather than quiet competence.

A new Progressive Conservative Party wouldn’t need to shock, disrupt, or shout to make its point. It would just need to speak clearly, stand confidently, and remind Canadians that most of us still live in the middle—even if our politics no longer does.

Chesterton’s Fence

In his 1929 book The Thing, English writer G.K. Chesterton offered a parable that has become a kind of first principle for conservative thinking. It goes like this:

“There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, ‘I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.’

To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: ‘If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.’”

It’s a short, sharp idea with a long shadow: before you tear something down—especially something old—you should understand why it was built in the first place.

This is what The Centre is all about.

Too often today, especially in politics, we skip that step. We see the fence. We don’t like it. We tear it down. Then we find out it was keeping the bull from charging into the village - or at least that something important was lost in the race for change and ‘growth’, for example as we are now discovering with globalism.

A Modern Reading

Imagine a Liberal and a Progressive Conservative walking through a field. They come upon an old fence, falling apart at the edges, cutting across what looks like perfectly walkable land.

The Liberal says, “That thing’s in the way. Let’s pull it down.”

The Progressive Conservative says, “Maybe. But let’s first figure out who built it and why.”

They poke around. Talk to a farmer. Look at an old map. Turns out the fence was once a firebreak, separating two forested areas prone to wildfire. It’s been neglected, sure. But with a few updates, it could still serve a purpose—maybe not as a fence, but as a path, a guide, or a marker.

Now they’re not arguing about whether fences are good or bad. They’re asking: what’s the best version of this idea for today?

That’s the heart of centrist progressive conservatism. It doesn’t fetishize the past, and it doesn’t bulldoze it either. It moves forward—but only after checking the footing. It asks questions before pulling triggers. It values what works, not just what’s new.

Why It Matters Now

Chesterton warned against tearing down fences without knowing why they were built. Maybe the same applies to political parties.

At a time when the major parties have veered into the ditches— yelling for revolution, or shouting about collapse—this kind of thoughtful, measured approach has never been more needed.

The centre isn’t the mushy middle. It’s the clearing where real solutions can be seen clearly. And Chesterton’s Fence reminds us that wisdom lives not in standing still, and not in charging forward—but in knowing why the road was built the way it was.

Rob, Tim, other provincial PC’s… it’s something to think about.

There is a lot to unpack here.

Frank Graves has been tracking the disappearing middle for some time—the middle has been disappearing from Canadian politics for many years and really no longer exists. What has replaced it is, on the one hand, a commitment to traditional “small l” liberal values of openness, inclusivity, and future focus and a belief that government is mostly a positive in terms of the services provided and intent, and on the other an “ordered populism” that is characterized by a distrust of government, science, is anti-immigration and pro “traditional family values” and all that goes with that.

There is a great paper Frank wrote in 2020 that you can find here:

https://www.ekospolitics.com/index.php/2020/07/northern-populism-2/

The “red Tories” of the Joe Clark era and prior would have held to those “liberal” characteristics but with a commitment to fiscal conservatism.

The demise of the federal PCs ended any commitment to “liberal” values in first the “Conservative Reform Alliance Party” (the appropriately named CRAP) which became the Conservative Party of Canada CPC—with all references to Progressive erased.

So, we don’t have a left/middle/right anymore—what we have is ordered populism on one side and various flavours of “open liberalism “ on the other.

Over a third of current CPC supporters *like* Trump and Musk, and almost none of the Green, NDP, or Liberal supporters do.

Now the Liberals have elected as a leader (and, full disclosure I voted for him) a guy in Carney who is a bit of a throwback to the red Tory type of leader. I suspect Joe Clark and Mark Carney would agree on quite a lot.

This election is going to be interesting to say the least. It is a test of how committed the Canadian electorate is, as a whole, to those small “l” liberal values by supporting a guy who could easily have been a red Tory, vs voting for an ordered populist who wants to tear down all of the fences.

Let’s get rid of party politics altogether . And adopt a system closer to municipal politics. Where the public has more immediate inputs and people are voted in for what they can bring to the table rather than political affiliation!