The Brutal Truth About Nova Scotia’s Secret War with America

How American Raiders Turned Nova Scotia Against the Revolution

Napoleon said "History is the version of past events that people have decided to agree upon." At least that’s what the history books say. George Santayana famously noted, "History is a pack of lies about events that never happened told by people who weren’t there." Similarly, Mark Twain quipped, "The very ink with which history is written is merely fluid prejudice." That’s all to say, take this story with a skeptical view and do your own research.

"What Happened When America Attacked Nova Scotia?"

The Jaw-Dropping Story You’ve Never Heard

When Donald Trump mused about the prospect of Canada becoming the 51st state, it may have sounded absurd to many. But this brand of brash American exceptionalism is nothing new. Indeed, it echoes the earliest days of American independence when Nova Scotia—wealthy, growing, and deeply tied to New England by family, trade, and shared culture—might easily have been expected to join the American Revolution. Instead, Nova Scotia chose loyalty to Britain, and the reasons why are tangled in a story of plunder, betrayal, and a brutal reminder of the costs of war.

The American Revolution Comes to Nova Scotia’s Shores

In the 1770s, Nova Scotia had every reason to feel an affinity for the revolutionary cause. Prosperous fishing towns dotted its coast, thriving on trade with Boston and other New England ports. Families intermarried, shared cultural traditions, and regularly moved back and forth across a border that barely existed. Many Nova Scotians viewed themselves as Americans in spirit. But when hostilities broke out, this harmony was shattered.

American privateers—legalized pirates operating under letters of marque—set their sights on Nova Scotia. These privateers, including some under the command of John Paul Jones, later celebrated as the “Father of the American Navy,” targeted the province’s wealth and strategic value. What began as a political revolution in Boston turned into a violent economic assault on Nova Scotia’s towns.

American privateers frequently sailed along the Eastern Shore, taking advantage of the region’s reliance on fishing and trade. These encounters often went unrecorded in detail but were part of a broader campaign to destabilize British colonies. Fishermen and small traders from Sheet Harbour to Guysborough reported losses to privateers throughout the war. It was these attacks that probably pushed British Loyalists and others trying to hide from American Privateers into other small Mi’kmaq and French communities along the Eastern Shore like Musquodoboit Harbour.

The Sack of Canso and Other Attacks

One of the earliest and most infamous incidents was the sack of Canso. American privateers attacked this bustling fishing hub, capturing ships, looting supplies, and setting fire to the settlement. The loss devastated the local economy and set the tone for further raids along the coast.

It happened in the summer fishing season of 1776, American privateers and naval forces targeted Canso. Privateering was a key strategy for the Americans, who used fast, privately-owned vessels armed with cannons to disrupt British trade and supply lines. Canso’s role as a hub for the cod fishery and its relative isolation made it an ideal target.

A small American fleet, including the Continental Navy’s Reprisal, captained by Lambert Wickes, and privateers such as the Washington, skirted Halifax and sailed along the Eastern Shore to Canso.

Their objectives were clear:

Disrupt British military provisions.

Capture or destroy British fishing vessels.

Secure supplies for the American war effort.

The raid was devastating for Canso. The Americans captured and burned British and loyalist vessels, destroyed fishing stages, and took supplies such as salted fish, vital for feeding troops. Many local fishermen and settlers were left destitute, their livelihoods ruined. A desperate situation in those days. Some were taken prisoner and transported to American ports or pressed into service.

Liverpool, another prosperous Nova Scotia town, was attacked multiple times. In 1778, American privateers descended on the town, plundering goods and burning property. The residents, determined to defend themselves, eventually armed their own privateers to retaliate. Liverpool’s privateers became a thorn in the side of the Americans, turning the tide of coastal conflict.

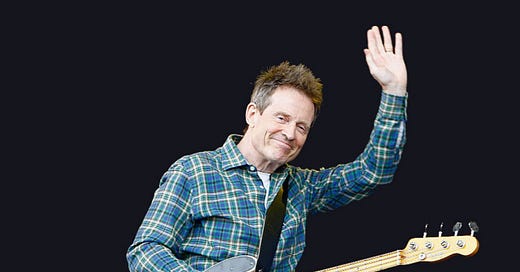

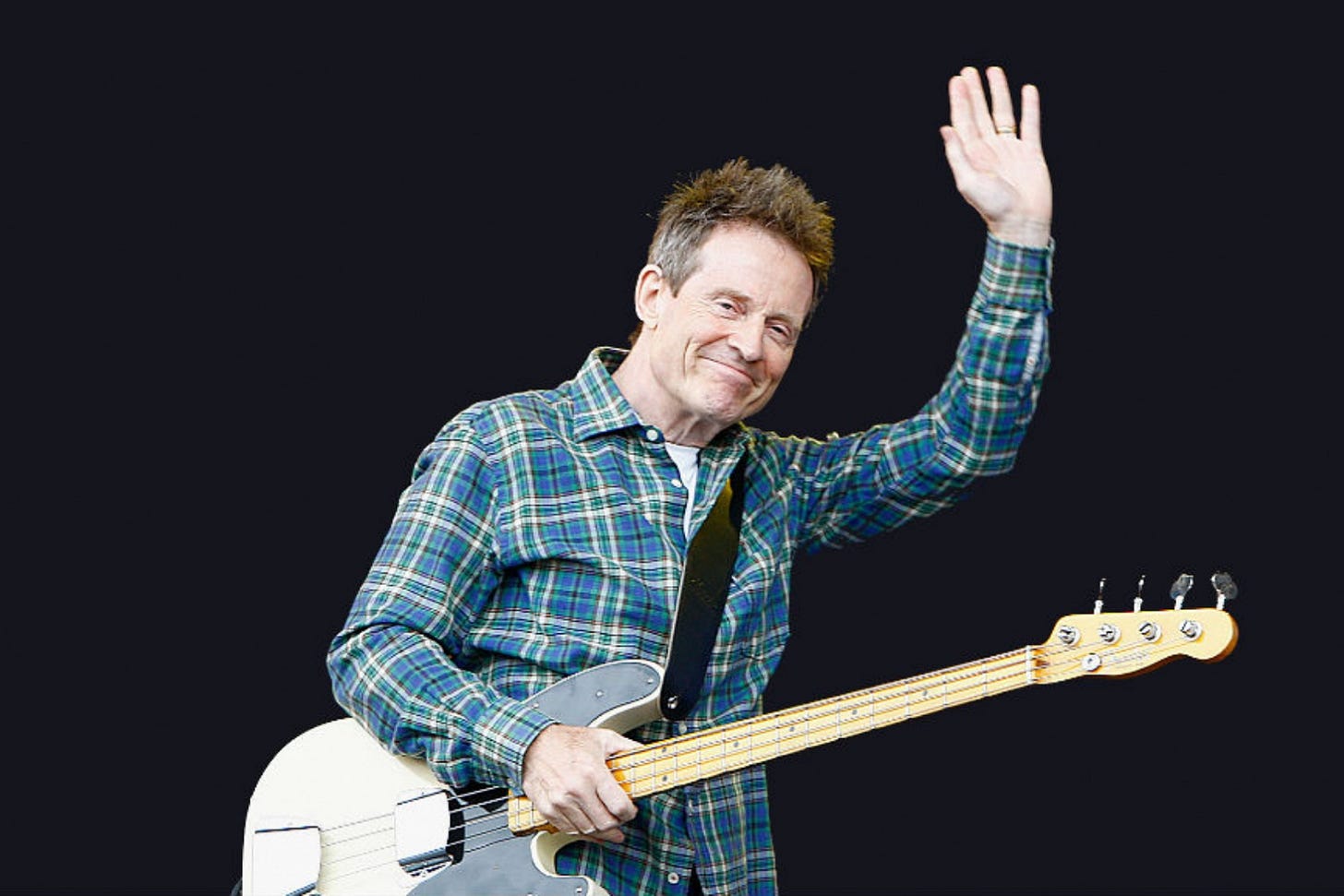

If you know anything about this story you probably got a sense of it from Stan Rogers's fictional song Barrett’s Privateers, which captures the story of a crew of fishermen from Sherbrooke who, now destitute and seeking revenge decide to outfit their own Privateering vessel. The tragicomic lyrics capture both the romanticism and harshness of life at sea, making it a timeless anthem for drunken and seasick sailors the world over.

Fun fact: Sherbrooke as an established place didn’t actually exist until about 50 years after the Revolutionary War, but Rogers liked it, at least musically, more than Canso.

John Paul Jones: Pirate or Patriot?

John Paul Jones—a polarizing figure depending on which side of the Atlantic you stand—is emblematic of the privateer-pirate dichotomy. While celebrated in the United States for his daring naval raids, Jones’s actions in Nova Scotia, on orders from Benedict Arnold, were viewed as outright piracy. In 1778, he led an attack on the fishing village of Lunenburg. Residents watched helplessly as their town was plundered and burned, leaving scars that would last generations.

The cumulative effect of these raids was profound. Once sympathetic to the American cause, Nova Scotians increasingly saw the revolutionaries as marauders rather than liberators. The privateers’ attacks unified public opinion against the rebellion, turning what might have been a natural ally into one of Britain’s most steadfast defenders.

Here’s an astonishingly glowing article from the Navy Times that describes in personal detail how the “visionary” John Paul Jones effectively created the doctrine of American Exceptionalism on the sea and conducted the first violent projection of American power under the ‘liberty flag’… in his attacks on Nova Scotia.

When Jones's ship was sunk beneath him during the Battle of Flamborough Head he famously said (but didn’t actually say), “I have not yet begun to fight” which has become an American battle cry for the ages.

As an aside, I got to spend many years with Clive Cussler searching for and researching the location of that ship, the Bonhomme Richard. It was Cussler’s white whale of a shipwreck.

Loyalist to the Core

By the end of the American Revolution, Nova Scotia’s loyalty to Britain was solidified. Thousands of Loyalist refugees, fleeing persecution in the newly formed United States, settled in the province, further cementing its identity as a British stronghold. When war flared again in 1812, Nova Scotians were more than eager to strike back. The province’s privateers played a key role in raids on the U.S. coastline, including the burning of Washington, D.C., an act often forgotten in American narratives.

The Long Shadow of History

Even a century later, Nova Scotia’s fierce independence—and loyalty to Britain—remained. Joseph Howe and the anti-Confederation movement resisted joining Canada in 1867, partly out of a sense of British allegiance. To this day, Nova Scotia’s history is marked by this complex relationship with its southern neighbor.

Lessons for Today? Not Really.

Trump’s musings about Canada as a U.S. state may be little more than political bluster, but they highlight the long, intertwined history of these two nations. Nova Scotia’s story reminds us that loyalty, identity, and sovereignty are not abstract ideas but hard-won convictions shaped by experience—sometimes at the barrel of a privateer’s cannon. And in the case of Nova Scotia, the scars left by American raids forged a loyalty that endured, if not to this day… because we don’t agree on any narrative of history anymore except that all white people are the worst ever people (because that’s what they teach kids in schools)... it at least held us and our culture in a contradictory balance for a couple of centuries.

no, no, just the British white people!

John Wesley,I enjoyed this Story . I was reminded of a song I was commissioned to compose For the Chester Heritage Society based on a poem from mid 1700 telling of the failed American attempt to invade Chester. Here's the story at this link http://jimhenman.com/1700s-poem-gets-new-life-as-a-song/n. JIm