The 25% Rule = Not Everyone is going to Like You

The surest way to be liked is never to say what you actually think. And even that only works some of the time.

Clinton, Illinois – September 8, 1858.

Here’s how I imagine it. It’s hot. A September scorcher where the harvest heat makes the corn sweat. The smell in the town square is all horse shit, wet wool, and hickory smoke from fatback and cornbread cooking in the oven on the edge of town. Clinton, a dusty railroad stop in central Illinois, has swelled ten times its modest size. Hundreds of people have poured in from nearby farms, homesteads, and towns, some walking miles through cornfields and axle-breaking roads just to see the tall lawyer from Springfield take on “The Little Giant,” Stephen A. Douglas.

Lincoln, wearing his trademark stovepipe hat and a suit better suited for cooler days, is already a crowd favourite- though not universally liked out here. Some lean on wagons, arms crossed. Others perch on barrels or hang from windows. At the back of the crowd pipe tobacco, dust, mix with vinegar of apple cider too long in the hot sun. There’s a carnival feeling to the crowd, but under it, a tension—the country feels like it’s it’s ready for a fight, and everyone knows the issue is slavery, no matter how they spin the speeches.

On a rough-sawn plank platform built across delivery wagons and packing crates, Lincoln steps up. His voice, American even then, easily carries across the square in that tone the victims of American tourists talking too loud know all too well today. No microphones—just something about the big open country that makes people louder. He’s been barnstorming across the state, trading stories of the future with Douglas in what history will call the Lincoln-Douglas Debates, though this stop in Clinton isn’t one of the “official” ones. Still, it draws a crowd all wanting to imagine America’s future.

Somewhere mid-speech, a heckler hits a short sharp shock. “Don’t Believe no long-legged lying lawyer.” The heckler is lost to time, but Lincoln’s reply is not. Calling someone a liar in public in those days was not like today. Someone might end up shot and quarrels that heated up could go on dangerously for years.

Lincoln stops, silent, and looks up over the crowd. In the rising quiet, it almost sounds like Lincoln cursed to himself. The crowd leans in to hear. His face changed. The melancholy book of grave lines smoothed out. It wasn’t his mouth so much - though it drew wider than you’d imagine possible - as it was his eyes that smiled and the spaces under his eyes told the story of a man who could take a punch.

“Well”, he gestures broadly to his many supporters, “You can please all of the people some of the time, and some of the people all of the time… but you can’t please all of the people all of the time.”

There’s a beat—a quiet acknowledgment that the line makes people stop and think. Then, laughter. It’s a long applause line and Lincoln lingers in it. Plus some grumbling from the other side. But there’s no comeback. It sticks. People would talk about that line for weeks—years, even. Reporters scribble it down. Local papers reprint it. By the end of the campaign, it has taken on a life of its own.

Lincoln finishes his story, his big boots kick up the dust when he jumps down from the podium into the crowd and buttons his coat in spite of the heat. Behind him, the bunting banners ripple. Ahead of him: the presidency, the war, and the weight of a nation splitting in two.

But for now, just a hot day, a loud crowd, and a line that somehow says it all.

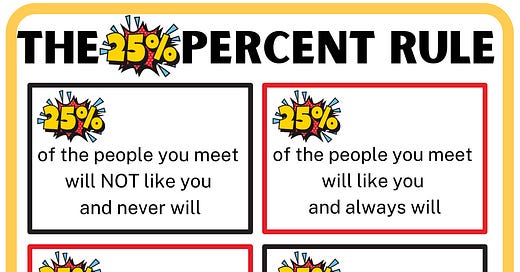

What you’re looking at is a simple, hopefully, comforting chart I’m calling The 25% Rule, though the idea is well known.

It says that, on average, people fall into four buckets when they meet you: 25% will like you right away and always will. Another 25% won’t, and never will. The other half is fluid—some will grow to like you, others will like you less over time. That’s it. Your results may vary. A little.

It’s a variation of the old saying, “You can please all of the people some of the time, and some of the people all of the time… but you can’t please all of the people all of the time.”

That’s the game. It’s not personal - it’s just how human nature works in the natural. And the higher you fly - socially, professionally, publicly - the more this pattern starts to look like a numbers game. But it gets more complex. You don’t like everyone equally. You're not the only one being judged—you’re judging too.

"You have enemies? Why, it is the story of every man who has done a great deed or created a new idea. It is the cloud that thunders around everything that shines.

Fame must have enemies, as light must have gnats. Do not bother yourself about it; disdain.

Keep your mind serene as you keep your life clear."

Victor Hugo wrote in his 1845 essay, Villemain.

Not everyone you meet in life is going to like you.

And the reverse is also true. You’re not going to like everyone you meet - at first, in the long run, or, for some, ever.

And that’s fine. It doesn’t have to divide us, frighten us, or hold us back from having a good time.

We can relax. The truth is, you will meet very few bad people. Liars, cheats, clinically diagnosables, mean, evil people are just really rare. And all those niche psychology terms folks love to throw around about narcissists, gaslighters, psychopaths and the rest just don’t add up to much more than a kind of modern social media ghost story. But they’re like shark attacks. Our experiences with them or stories we’ve heard – all great stories have a villain – have misleading vividness.

In logic, Misleading Vividness is a Logical Fallacy where a small number of dramatic and vivid events are taken to outweigh a significant amount of statistical evidence. A few years back when shark researchers started pointing out that more people are bonked on the head by coconuts than are bitten by sharks, this misleading and oft-misquoted fun fact led local officials in Queensland Australia to cut down the coconut trees on their beaches in 2002 to avoid liability… thereby both proving and totally missing the point of the fallacy of misleading vividness.

Colin Wilson’s landmark book, The Criminal History of Mankind, cites studies that point to roughly:

5% of a given population actively and purposefully doing good (acting altruistically, and playing by the rules) almost without fail,

5% doing evil (or, more accurately, acting selfishly, even criminally so) almost without fail,

And the remaining 90% of us are doing good when we can, obeying rules to our detriment when we have to, but getting away with minor misdeeds to our advantage sometimes, often feeling pretty darn bad about it and going to great lengths to apologize, make amends, and do other kinds of repentance.

The problem is, as Malcolm Gladwell reveals in Talking With Strangers, we’re not just bad at telling who’s who, we’re terrible at it, and it’s evolutionarily ingrained in us to be bad at it. Even simply telling when someone is lying, which many believe they can do, is more fraught than most imagine.

Something is very wrong, Gladwell argues, with the tools and strategies we use to make sense of people we don’t know as well as we could. Our lack of understanding is a big blind spot. And because we don’t know how to talk to strangers, we are inviting conflict and misunderstanding in ways that have a profound effect on our lives and our world.

Admiral H G Rickover, the father of the nuclear navy and one of America’s most outspoken 20th-century critics of modern education, wrote that one of the central challenges of education should be to understand, appreciate, and learn to live with the fellow inhabitants of our planet. Every child must learn about the races and people of the world and the rich variety of the world's cultures, people, and personalities. They must know something of the history of people and nations. They must learn that there are many people in the world who differ from them profoundly in habits, ideas, and ways of life.

We must perceive these differences, these likes and dislikes, not as occasions for uneasiness or hostility but as challenges to our capacity for understanding.

Eddie Jaku is famously known as the happiest man on earth. He was also a concentration camp survivor. Like Dr. Viktor Frankl, a survivor of Auschwitz, Eddie describes a search for a life's meaning as the central human motivational force with other people at the centre of all thinking.

You get to decide

Whether you like ‘em or they like you or not, are people basically good or bad?

Would you say that the world is a good and safe place or a bad and dangerous place?

You might respond, “It depends on the circumstances,” and that is no doubt (sometimes) true, but go deeper — to your core or “primal” belief.

It’s important because your deep answer is the main thing that determines whether or not you, and by extension, many of those around you, will have a nice life or not.

Our Beliefs Shape Reality

Our beliefs about the world are not shaped by our experiences so much as our “primal beliefs” determine how we interpret those experiences. If our primal belief is that the world is basically a good and safe place, we will likely find positives in even the most difficult circumstances as indicated by Frankl, Jaku, and the testimony of other concentration camp survivors.

If our primal belief is that the people we don’t connect with are all dangerous and the world is a bad and dangerous place, on the other hand, it will colour or call into question our interpretation of even the most positive life experiences.

Today leading psychologists like Jer Clifton Ph.D. are exploring how much our basic beliefs shape our lives, our world, and the people in it.

“Broadly speaking, human action may not express who we are so much as where we think we are, and much of what we become in life—much joy and suffering—may depend on the sort of world we think this is.”

This is a thought-provoking article - as it's meant to be. Tragically, too many people are just punching the clock, not bothering with giving much time to such questions as, "Why are we here?"

I don't engage in queries about philosophy, theology, sociology, or psychology for the sake of 'intellectual masterbation', but because of the fact the odds of either me or my wife still being alive are less than 1% due to a variety of events and challenges. Continued existence despite the odds prompts such pensive consideration, while being a combat veteran tints such consideration with first-hand knowledge of just how good and evil persons can be. Combat doesn't only bring out the very worst in humanity, but the very best as well.

The conclusion: Love isn't an emotion, but it's a decision - a decision to set someone's well-being, best interest, and happiness as a priority; and that our purpose is to love and to be loved. Everything else is ancillary to that decision. Most people have come to that conclusion to some degree, albeit not in so many words, and those who are the furthest from it tend to be psychologically pathelogical. Most anguish in the world is prompted by the latter group of persons.