“White Enamel Will Cover All This Up!”

It was very late in her life when I took my mother to see The Jubilee House for the first time. I could see her heart and hopes sink when she came through the door. Admittedly, it was in pretty bad shape after being left empty for years. The developer who bought it when Bouffie, the long-time owner died, had intended to tear it down before I stepped in.

“You spent all your money on this?”, she said. It wasn’t a question. It was an accusation. It wasn’t the disrepair that bothered her so much as the dark wood. It was everywhere. Still, ever the optimist, she pulled herself together and gave the best most hopeful advice she could muster. Frantically waving her arms at … well, everything, she said, “white enamel will cover all this up.”

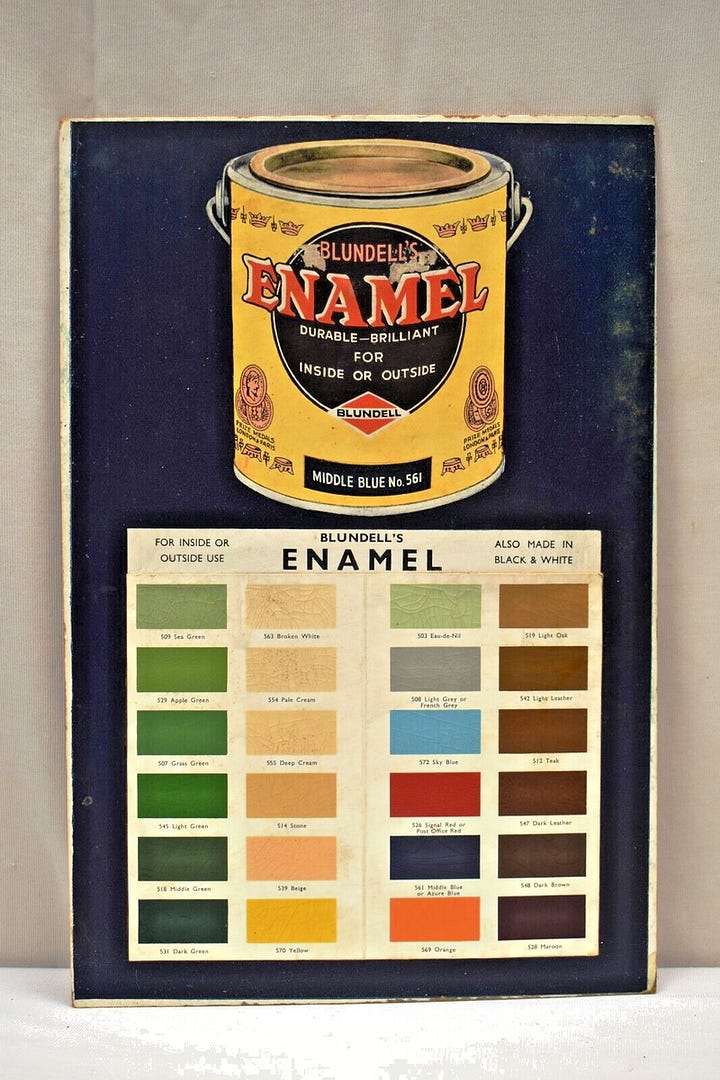

I knew exactly what she was talking about. Growing up I’d seen it in almost every home I’d been in in Nova Scotia. Thick white enamel, with its hard, smooth, and glass-like glossy finish covered baseboards, cabinets, kitchens, and basically everything that might have once shown the character of wood, wear, and time.

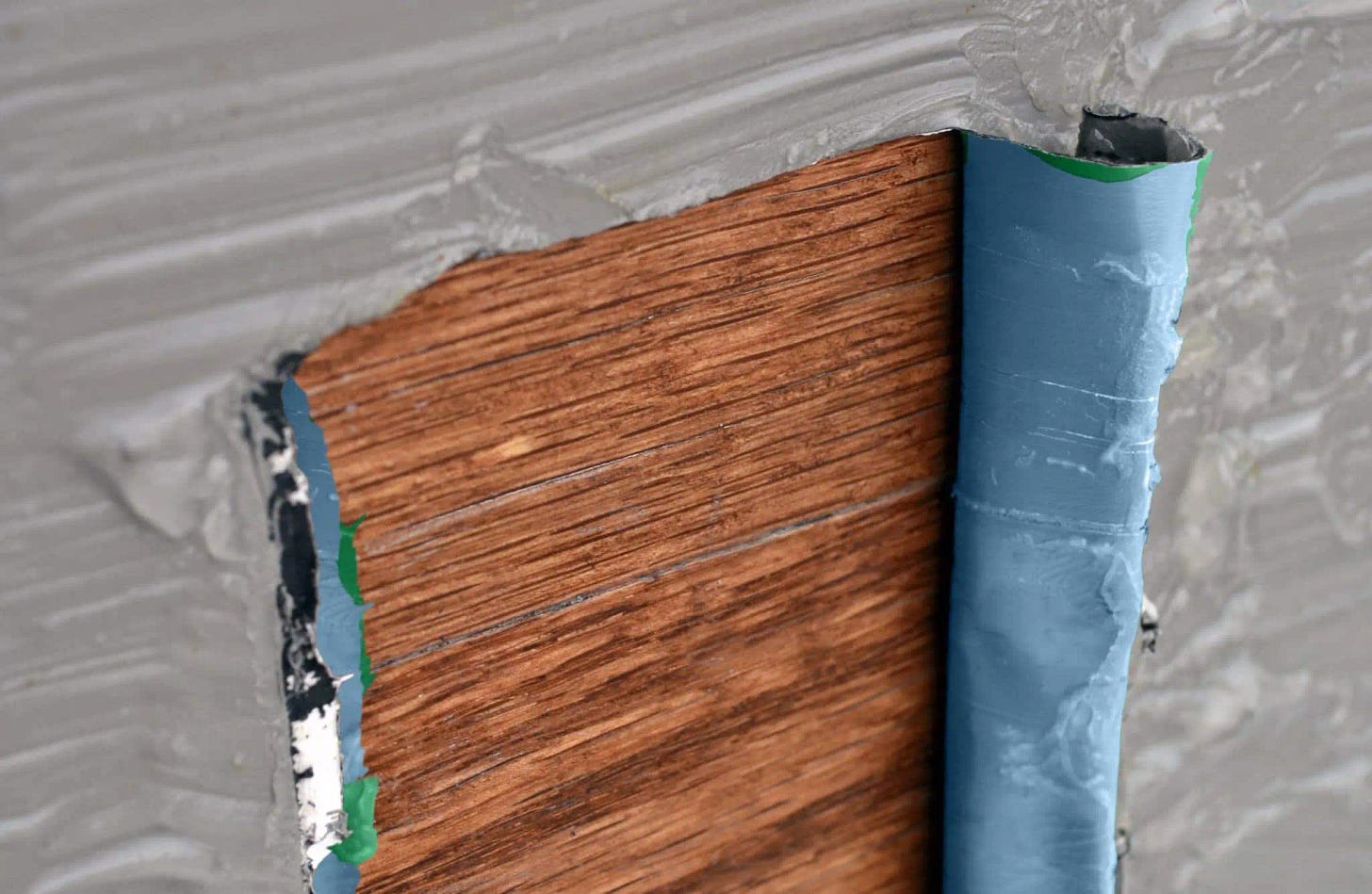

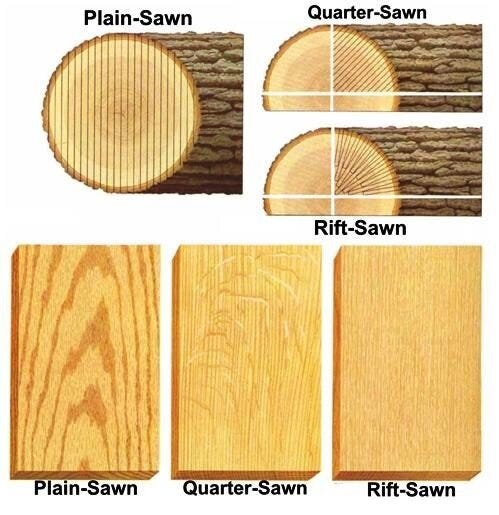

Here and there I’d seen glimpses into the past through cracks and chips where something had banged the enamel, or been thrown, such that it revealed the wood, often the dark lines of quarter-sawn oak, smooth worn wide pine, or some hallmark of local hardwoods and shellac.

The Glossy Generation

After the war, life was about new beginnings. The soldiers came home, the women who’d run the home front traded factory tools for frying pans, and the world turned to the business of living again. It was an era defined by optimism, but optimism didn’t come easy. It required effort—a scrubbing away of the old, the heavy, and the dark. And nothing symbolized that transformation quite like a fresh coat of thick white enamel paint.

Our grandparents, the greatest generation, were pragmatists. They had survived the Great War, the Great Depression, and another war that blackened the skies and the soul. By comparison, old woodwork seemed a small thing to conquer. Sturdy, yes. Beautiful, perhaps. But its dark grains felt out of step with the mood of the times. It seemed so unlikely with much of the world in ruins, but somehow they came out of it happy and hopeful and headed into one of the greatest eras of human flourishing the world has ever known. The country wanted brightness, hope, and cleanliness—qualities that couldn’t be found in the shadowy recesses of quarter-sawn oak.

They Laid It On Thick

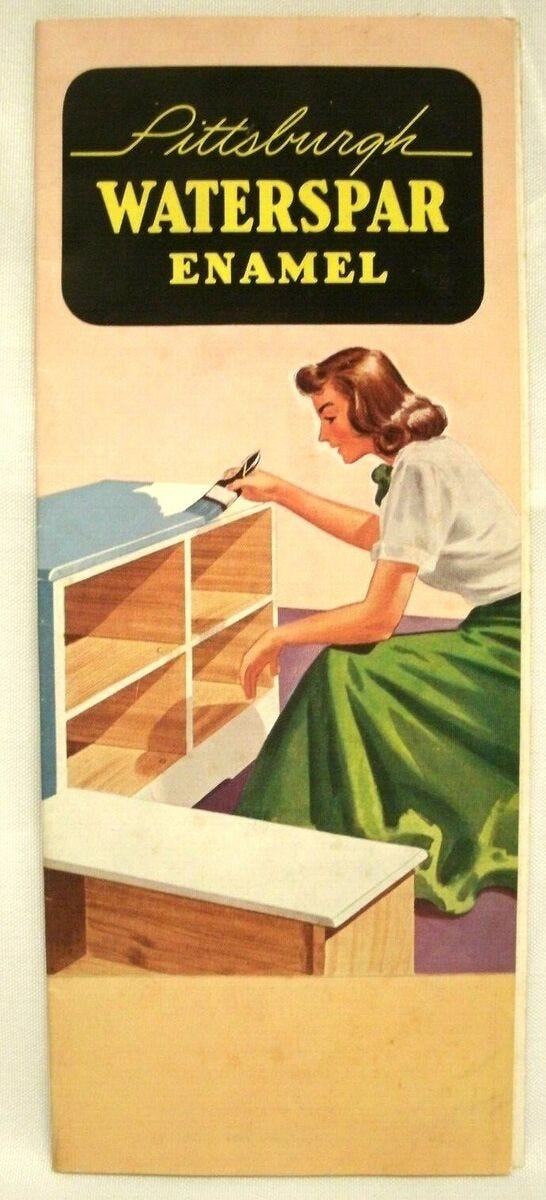

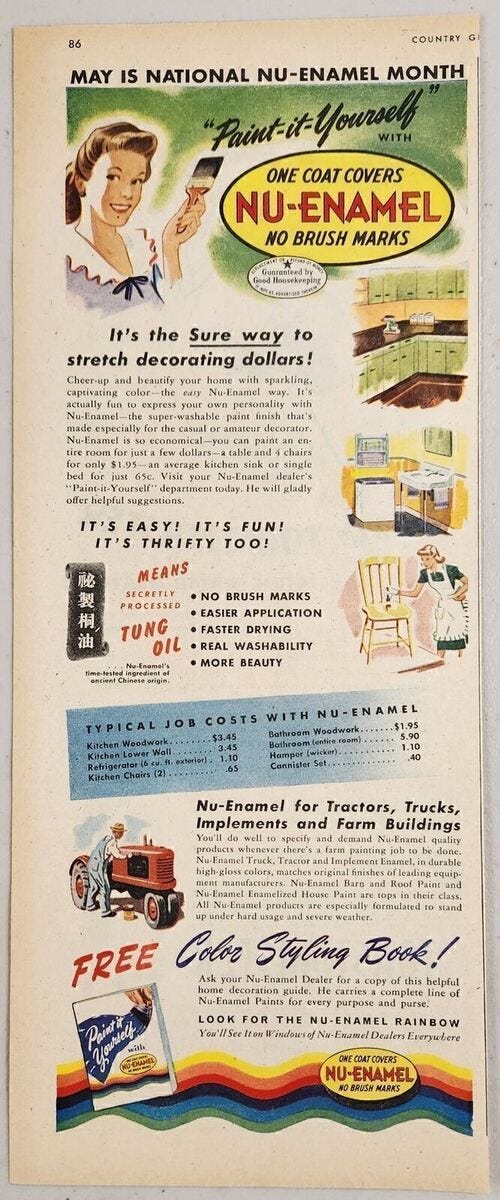

Thick white enamel paint arrived as both a miracle and a mandate. Advertised in magazines as "the modern solution" for dull and dowdy homes, it promised transformation in a can. Kitchens would become cheerful hubs of domesticity. Parlors would lose their gloom. It was the color of purity, of blank slates, of a world reborn.

The brushes were dipped and the change came fast. Maple cabinets once rubbed smooth by hands from another century disappeared under a gloss so shiny you could see your reflection. Quarter-sawn oak paneling, with its tiger stripes and timeless strength, was swallowed whole.

Wainscoting, balustrades, and banisters fell like dominoes to the brush. The effort felt noble, almost moral, a banishment of pre-war shadows to make room for the bright American future. Painfully even parlor pianos didn’t escape the brush. Imagine - once the most valuable musical instruments most people would ever see, prized possessions intended for generations, built and finished by our best craftsmen, slathered with thick enamel paint before eventually being discarded on some buy and sell site.

When Music Was Home

I walk by it sometimes when the house is quiet. My Grandmother’s piano. In the soft light filtering through the window, I can still see how the finish once shined. It stands there waiting and whispering like sunken treasure. The kind of thing that is priceless but can’t be bought, sold, or spent. A silent witness to a deep, different era, one that feel…

It wasn’t just the wood that went white. It was the iron radiators, the clawfoot tubs, and even the basements—sprawling root cellars that became fluorescent-painted "rumpus rooms." The past, with its muted earth tones and hand-crafted detail, was considered too heavy for a generation unburdening itself of memory.

At the time, few questioned it. They were too busy reupholstering sofas in floral prints, watching the new televisions, and building ranch-style homes to wonder what had been lost. To them, white enamel wasn’t an erasure; it was an improvement. Who wouldn’t want the world to feel brighter after so many years of poverty, depression, and letters bearing bad news?

The Guilt of the Grandchildren

It wasn’t until decades later, in the 1980s and ‘90s, that their grandchildren began peeling back the layers. The first attempts to strip the enamel were met with shock. Beneath the paint lay a buried treasure—a world of craftsmanship that told the story of another time. Quarter-sawn oak stairs re-emerged like artifacts in an archeological dig, their grain whispering of forgotten forests and artisan hands. Maple cabinets, bruised but enduring, reclaimed their rightful place as the heart of the home.

The guilt set in. What had they been thinking? Why had they hidden such beauty under a chemical veil? “Strip and Dip” shops proliferated. Even my father contributed to the Renaissance, artfully staining and refinishing desks, chairs, kitchen tables, and old toys found hidden under layers of enamel.

But this criticism came from a generation that had never known hopping a train to find work or held a letter from from a ship at sea. It was easy to mourn the loss of oak paneling when you hadn’t lived in the shadow of history’s darkest chapters.

A Lesson in Perspective

There’s something both tragic and triumphant about that era of white enamel. Tragic because it covered over the artistry of a slower, quieter time. Triumphant because it spoke to a generation’s relentless determination to make their world better, even if “better” was an oversimplified concept. The white enamel wasn’t just paint—it was armor against despair. It was proof that they could take control, take action, and banish darkness, one brushstroke at a time.

As we sand and strip and restore the woodwork they hid, perhaps it’s not judgment they deserve but gratitude. After all, we are not the generation who rebuilt the world with paint cans and hope. We are merely caretakers, peeling back the layers to reveal their story. The woodwork beneath the enamel isn’t just ours to admire; it’s theirs, too, carrying the legacy of hands that touched it before ours, first with Shellac and varnish and later with a rainbow of enamel paint.

Maybe the white paint wasn’t a mistake but a kind of love letter, the last from that chapter of history—a reminder that beauty isn’t just in preservation but in the story itself, in the ever-hopeful attempt to brighten our worlds.

It was just about the paint... but oh, man, you are going to hate the next story, which this was really just a setup for.

Okay, I may have just completed my one and only reno but I've seen plenty of them while my father moved us around two countries and we lived in construction for most of it. So I speak here with some authority. Your house is lovely and it's very well built with lots of delightful design cues and good, no, great craftsmanship all around. Not every old house is like that.

I've seen messes like you wouldn't believe. I mean, sure, with a functionally unlimited budget you could restore them, but with a functionally unlimited budget you'd probably just pick something in better shape with more character to begin with. Some of these problems began with the original house or house design too, the enamel coating was just "lipstick on a pig" to begin with.

So yeah, I would agree that most of the new design after the war was pretty execrable. The "Ladies Home Journals" and "Better House and Gardens" of the day were full of stripes on plaid on check with parquet floor. All of that was an effort to sell, sell, sell home building supplies, paint and decor. The "Property Brothers"/HGTV of its day. And yes, it sucked. I agree. It also did in a lot of Victorian (and earlier) homes that had beautiful features but let's not give all Victorian homes a complete pass. Nor should we scourge all other home styles either. I've seen nice functional ranch homes with good detail and charm too.

The trick, it seems to me, is to start with good or great design and vision. There is a lovely Victorian home in Sacramento where the front porch (about 5 feel wide by 15 feet long) was lined entirely with a single 6 inch wide bent wood log along the entire edge. So the log had to have been at least 45 feet tall to begin with and then they had to bend that into a 3-D shape with (probably) steam. No seams, one tree. Now that's craftsmanship. And it's just a log, but wow does it ever stand out! Equally though, a Neutra house in Palm Springs is using new materials and techniques to create a soaring, light, airy open space that just seems like it isn't there. The flow and design just invite you to swim in the pool in the hot evening breeze. It's also delightful. And the Green and Greene and Greene Gamble house in Pasadena uses all that heavy, dark wainscotting to combat the nearly blinding (and too hot) sun of Southern California summers. Using the heavier designs of the Craftsman style also solves a "problem" of too much light (and heat). Great design is marked by not only craft but also by the designer or architect directly dealing with whatever issues are present in either the materials or location of the home, ideally both or using one to solve the other.

Sure, you can oversimplify that all craft used to be better. It was, in the case of houses for the rich, but not ALL homes, I assure you. But it's just as simple a way to look at things as solving it all with a coat of enamel. There are plenty of drafty, cold, cramped, unfit for the location older homes out there that really should be updated. Maybe not with a coat of paint, if it's in that bad of a shape from the get go then a coat of paint won't fix it. I mean there are some lovely chateau in France too that have great things going for them but if you want to add a modern kitchen or use wi-fi then good luck with those thick stone walls! And while the lovely chateau survive, some more intact than others, almost none of the cottages or hovels from the 15th century survive. There's a good reason for that. They sucked!

On the other hand I encourage your readers to read a few "Better Homes and Gardens" archived magazines from the era. It's shocking what marketers will try to get you to believe to sell more white enamel paint.