Snowmobiles, Capitalism, Toboggans, and Losing Our Ability to Make Stuff

Kind of a Stompin' Tom meets Bruce Springsteen story about snowmobile factories and how Canada's industrial lobotomy got billed as progress

We’re at that part of winter that makes some folks start thinking of snowmobiles. And we’re at that place in the snowy woods of an economic winter where Tariffs and Trade Wars are being worried about. It is worth getting right at the heart of the story of why we don’t make our own stuff with our own resources. But I’ll take the long way around.

Though four-wheelers are maybe more common sights along the ditches and treelines of highways these days, it’s not uncommon as you float along Nova Scotia’s highways in cruise-controlled comfort through rural areas to see the winding track of snowmobiles through the deep snow along the ditches, embankments, and treelines.

I always found these undulating tracks hypnotizing - imagining the fun of being on those machines out in the drifts and valleys of snow on the way to a lake or hidden cabin somewhere in the forest made accessible for a few weeks of winter.

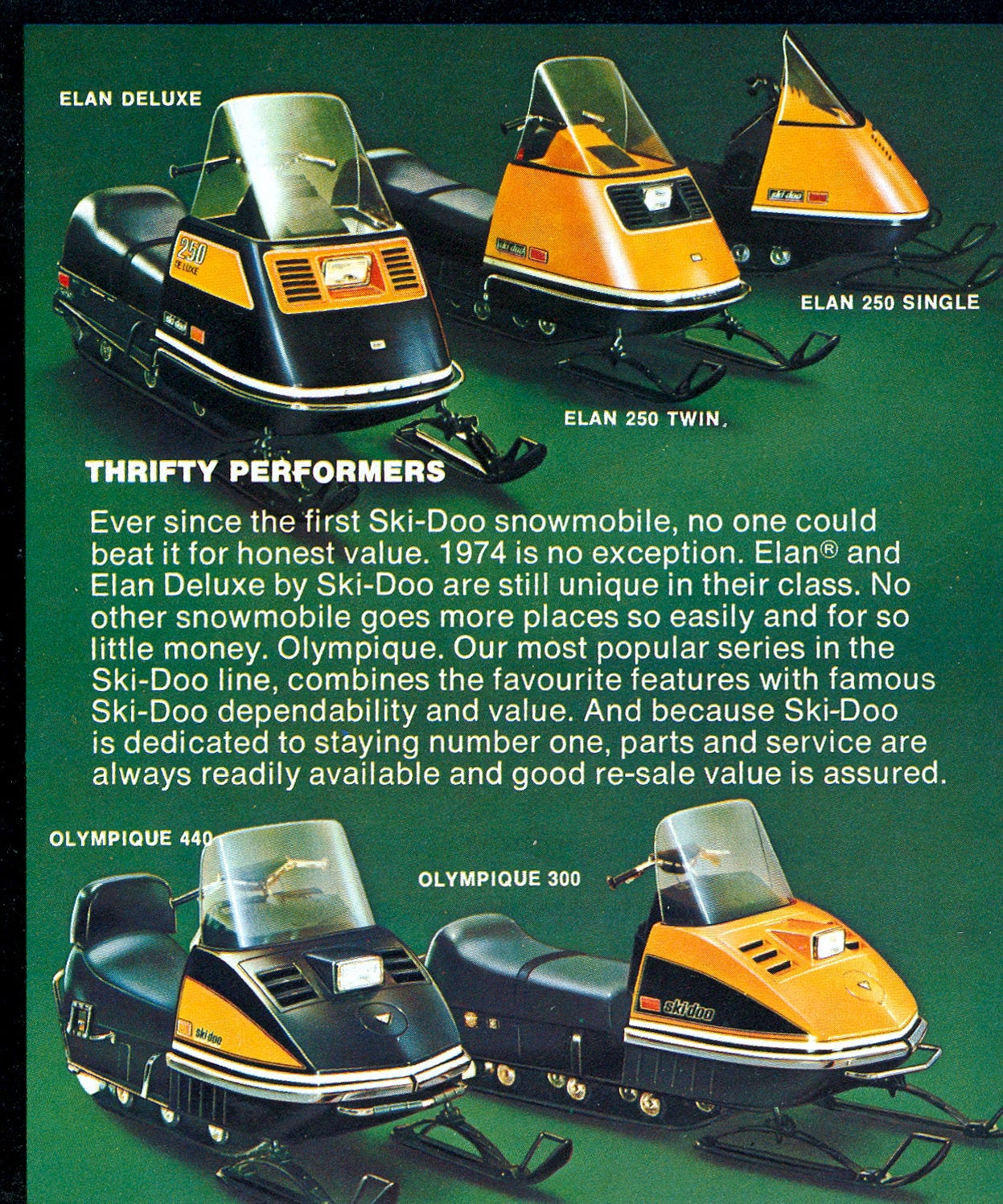

These are the snowmobiles I grew up with. The fun, winter, and youth itself didn’t last long. But there were some good times on these machines. It wasn’t about going far or fast, but they made every snowfall a celebration. When the snow covered the ground, they covered the ground, at the kind of pace a bicycle does. Just a little faster than walking or running, you get a feel for the land, the geography that’s dreamlike. And then, just like that, they were gone.

There was a time when North America was a land of tinkerers, builders, and independent business people who understood that prosperity wasn’t bestowed by government decree but forged in garages, workshops, and factories. Look no further than the history of the snowmobile—a machine born of necessity, perfected by ingenuity, and once manufactured by over a hundred competing companies in Canada and the United States. The snowmobile was more than just a vehicle; it was an industry, an economy, and a symbol of the kind of rugged individualism that once defined us.

Now, it’s a relic.

Today, only a handful of corporate behemoths remain—Bombardier, Polaris, Arctic Cat, Yamaha—swallowed up, consolidated, and mass-produced in overseas factories. The independent manufacturers, the backyard inventors, the small-town fabricators who once built something from nothing? They’ve been wiped out, not by superior competition, but by an economic system that rewards monopoly, punishes innovation, and treats local industry as an inconvenience to be offshored at the earliest opportunity.

From 100 to 4: The Corporate Strangulation of an Industry

For a brief, shining moment in the 1960s and 70s, the snowmobile industry represented the best of free-market capitalism. Competition was fierce, with brands from every snowy region throwing their hat in the ring—Scorpion, John Deere, Rupp, Sno-Jet, Boa-Ski, Alouette, Moto-Ski, Chaparral, Evinrude. They weren’t just making machines; they were making jobs, wealth, and a culture of self-reliance. These weren’t government-sponsored, subsidized, or imported—they were built by North Americans, for North Americans.

Then, one by one, they were crushed.

At first, it was the standard culling that happens in any booming industry—some companies failed to keep up with innovation, some overexpanded. But then came the real death blow: the rise of mega-corporations, leveraged buyouts, and the deliberate destruction of smaller competitors. The surviving companies didn’t win because they made the best machines; they won because they bought, absorbed, or killed the competition. Yamaha leveraged Japan’s rising manufacturing dominance to flood the market with cheaper units. Bombardier used government-backed funding to squeeze out Canadian competitors. Arctic Cat and Polaris consolidated, bought out struggling brands, and shuttered their factories. By the 1990s, the industry wasn’t an industry anymore—it was a cartel. Or as Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden, and others want to bring back to the lexicon, Ogliopoly.

What Happened to Innovation? It Wasn’t Killed; It Was Outsourced.

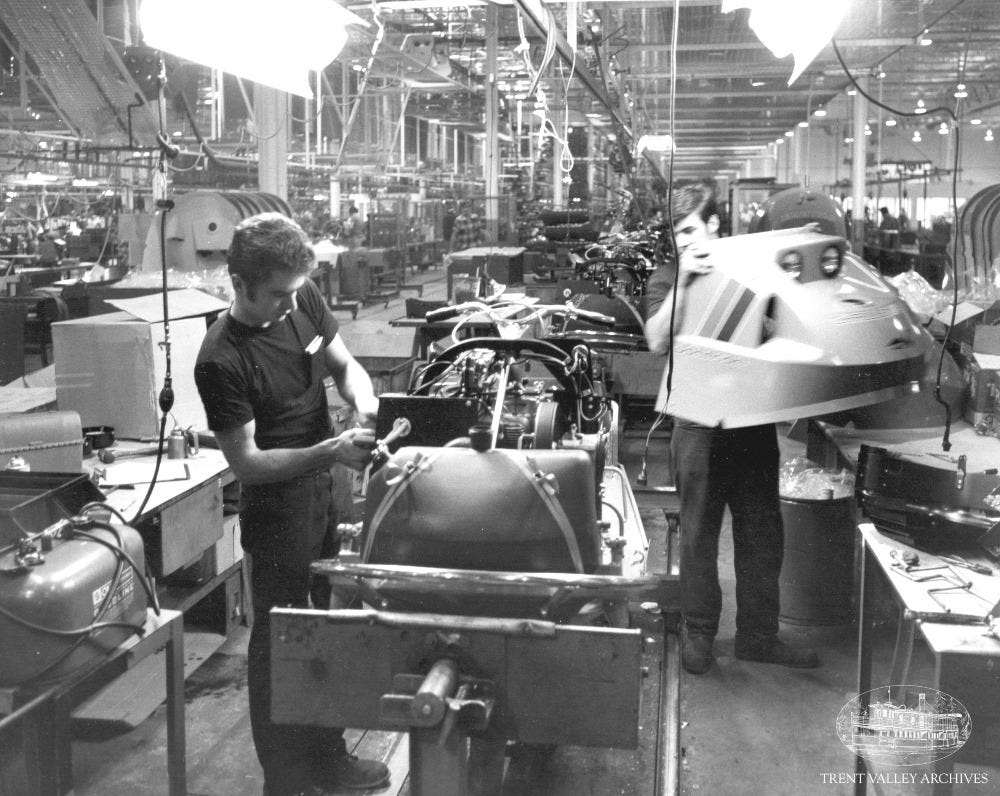

With the death of competition came the death of true innovation. The first snowmobiles were built by necessity—farmers, loggers, and inventors bolted engines onto sleds because they needed to get through deep snow. They experimented, refined, and improved. Once, American and Canadian engineering prowess led the way. Now? Manufacturing has been offshored to Asian megafactories, where cost-cutting trumps craftsmanship. What used to be made in towns like Valcourt, Quebec, and Thief River Falls, Minnesota, is now assembled on the other side of the world by people who’ve never seen snow.

This isn’t progress. It’s a lobotomy.

Mergers, Acquisitions, and the Great Hollowing Out

“Progress is a fine thing, but it's gone on too long” Ogden Nash

This story isn’t unique to snowmobiles. It’s happened to everything—cars, tools, furniture, electronics, even our food. Once upon a time, North America had hundreds of independent breweries, distilleries, and small farms. Today, nearly everything you drink, eat, drive, or wear is owned by one of a handful of corporate leviathans. Nestlé, Unilever, Procter & Gamble, PepsiCo, Kraft Heinz, General Motors, Toyota, Amazon, Walmart, Disney. They’ve swallowed entire industries whole, consolidated power, and made it nearly impossible for small businesses to compete.

The result? A world where choice is an illusion, independence is a myth, and nearly everything we consume is dictated by the decisions of a handful of boardrooms. The ability to build things—real things, tangible things—has been systematically erased.

We’ve traded ingenuity for efficiency, independence for dependency, and competition for compliance.

The Third Nail in the Coffin: The Loss of Capital

We haven’t lost the creativity, the drive, or the raw materials. We haven’t lost the ambition, the ideas, the opportunity, or the reward system. We’ve only lost access to one main ingredient in the capitalist system—capital. Unlike the insecure consumers buying over-hyped but fake machines—fake racers, fake tough trucks, fake transformers with aggressive angles and ridiculous paint jobs—we haven’t lost the most important masculine quality of all: improvisation. The ability to take the resources at hand and make something.

What’s holding us back? Rules, certainly. Corporate-created barriers to entry, absolutely. But capital is the real missing ingredient. Lack of capital is why we can’t get started, let alone succeed or fail. The factories, the jobs, the encouragement would all return like spring forests if the capital were not frictionlessly drained from our regions. Without access to capital, there is no capitalism. Most of those complaining about capitalism run wild are mistaken—capitalism does not exist without broad access to capital. The system we live in, named or not, is something else altogether.

And yet, even if capital were available, would anyone be allowed to build? The bureaucratic web of permits, approvals, and regulatory strangulation ensures that innovation never makes it past the garage. In the 1960s and 70s, an ambitious person could build a snowmobile, refine it, and start selling it—without first spending years navigating an obstacle course of government approvals and safety regulations designed not to protect consumers, but to block new entrants from competing with corporate giants.

Now, even if you managed to assemble a snowmobile, the hoops you would have to jump through to bring it to market would be insurmountable. Environmental impact assessments, emissions testing, safety certification, liability insurance—each one an individual hurdle designed to crush the small innovator and ensure that only those with deep corporate pockets can participate. The laws that were meant to ensure safety and fairness have become weapons wielded by entrenched powers to eliminate competition before it even begins.

This Isn’t Nostalgia—It’s a Wake-Up Call

Some will read this and scoff: "You just don’t like change. Things evolve."

No. That’s not it. Change is supposed to be driven by invention, by better ideas winning out, not by corporate consolidation and regulatory strangleholds that prevent anyone new from even trying.

The world didn’t move past snowmobiles; it crushed an industry that could have continued evolving, employing, and creating. The same has happened in aviation, shipbuilding, consumer electronics, and nearly every other industry where we once led. The reason we don’t make things anymore isn’t because we forgot how—it’s because the system has been deliberately designed to prevent us from trying.

The Way Back

This isn’t irreversible. There’s a way back, but it requires a conscious rejection of the status quo. It means choosing small over big, local over imported, and competition over monopoly. It means breaking up these corporate oligarchies, rewriting the rules of trade, and making it possible for innovators and builders to rise again. It means understanding that an economy based on service jobs and digital products is not a real economy—it’s a house of cards.

We need to start making things again. Real things. Things you can hold, ride, use, and pass down. The snowmobile industry was a glimpse of what we once had and what we could have again.

This isn’t about nostalgia. It’s about survival.

If we don’t reverse course, we lose more than the snowmobile industry. Or even industry in general. We’ll lose everything.

Coasting to Success - Let’s make things that matter and agree that it matters how and where they are made

That seems a negative note to end on. So here’s a good story. There may not be a path to build snow machines in the Maritimes. But for way over 100 years we’ve been commercially building Canoes, Toboggans, and Sleighs. Here’s the story of a company in New Brunswick drawing on these traditions, building as many canoes and toboggans as their capacity will allow… and winning awards and races doing it.

In the heart of New Brunswick, Miramichi Canoes exemplifies how small-scale manufacturing can thrive by embracing tradition, quality, and local resources. A place where it matters how things that matter get made. With over 40 years of experience, this Doaktown-based company specializes in crafting traditional cedar canvas canoes, heirloom toboggans, and kickass kick-sleds, all using locally milled lumber.

The company's commitment to local sourcing not only ensures high-quality products but also supports the regional economy. By utilizing local materials and craftsmanship, Miramichi Canoes contributes to the sustainability of New Brunswick's forestry sector, which, as of 2016, generated over $1.7 billion in economic impact and supported approximately 9,725 direct jobs.

The takeaway from this canoe story is not obscure. It's been well known since the dawn of capitalism. Using skills, knowledge, machines, and technology to add value to raw materials (in this case wood) is both at the heart of the definition of capitalism and the key to human progress.

What the globalist economic theories missed when relying on their theories like Comparative Advantage (I’m writing another essay just about this) is that there is more to the world than efficiency. The art and craft of creation adds immeasurably to our culture. Work is the fundamental way humans connect to the world and each other. Having someone value the output of your labour gives life a sense of purpose. If Canada continues to sell raw materials and buy back disposable finished such that the cycle just repeats it's not just an economic loss. It's the loss of our culture, heritage, purpose and prosperity.

In response to market demands, Miramichi Canoes expanded its product line in 2020 to include traditional wooden toboggans. This strategic move not only diversified their offerings but also tapped into a growing interest in outdoor winter activities. The introduction of these toboggans was met with enthusiasm, leading to significant sales and further establishing the company's reputation for quality craftsmanship.

It also enabled a New Brunswick team to win the US National Toboggan Championsips!

And if you are interested, Miramichi Canoes offers hands-on experiences, such as build-your-own-canoe workshops, fostering a deeper connection between consumers and the manufacturing process. These initiatives not only generate additional revenue streams but also promote the preservation of traditional skills and knowledge. And that need is at the heart of all this.

By maintaining a focus on quality, sustainability, and community engagement, Miramichi Canoes demonstrates that small-scale manufacturing can be both profitable and beneficial to the local economy. It can be fun too! Their success shows there is nothing new under the sun. Progress is great, and we’ve had more than our share over the last 200 years. But that doesn’t mean that all progress and new things are good unconditionally. When it comes to toboggans and canoes - good enough for Grandma, good enough for me.