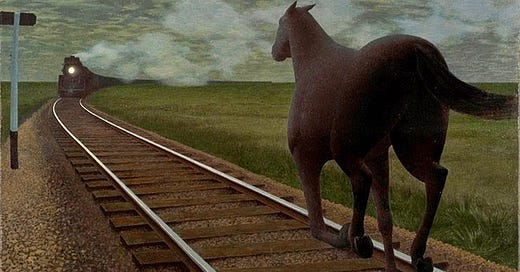

Alex Colville’s 1954 painting Horse and Train shows a lone horse charging head-on toward a speeding locomotive, symbolizing the clash between nature and unstoppable progress. We don’t need to see the next frame. We know this ends badly. When it first emerged, it resonated with a post-war world grappling with rapid technological change, industrialization, and the growing power of governments. The painting became iconic as it captured a universal feeling of helplessness in the face of modernity—where growth, like a train, seems inevitable and overwhelming. It speaks to humanity’s struggle to retain control, dignity, and independence in a world increasingly dominated by machines, bureaucracy, and the powerful forces driving society forward.

Progress vs. Growth: Individuals vs. The Machine

When political discourse in Halifax (and many other cities) shifted from jobs, jobs, jobs to growth, growth, growth, something fundamental changed. It wasn’t just a new slogan—it marked a shift in focus, from individuals and their experiences, to systems and their efficiency. In the past, the rallying cry for jobs was about people: about creating opportunity, fostering purpose, and enhancing quality of life. It was about ensuring that citizens could find meaningful work, provide for their families, and build futures within the fabric of their communities.

But with the new emphasis on growth, the conversation has shifted away from individuals to a focus on the system itself. Growth is now measured in square footage, GDP, tax revenues, and other metrics that are disconnected from the lives and experiences of regular people. Halifax’s shift towards urban and up expansion, high-rises, and real estate booms mirrors a broader trend where growth is valued for its own sake, with little consideration for its limits or impact on the average resident.

The Difference Between Progress and Growth

This shift reflects a larger distinction between progress and growth—two concepts often conflated by the political class but fundamentally different in meaning and outcome.

The term "world-class" became the buzzword of urban planners and politicians at the turn of the 21st century, signaling aspirations to compete on a global stage. But as cities raced to be “world-class,” they began sacrificing local character for soulless skyscrapers and mega-developments, all in the name of GDP growth. Instead of fostering prosperity for citizens, this vanity project fueled inequality, with rising costs of living and stagnant wages. Chasing “world-class” status, cities now resemble each other in a bland, homogeneous dystopia, where growth doesn’t mean wealth, and bigger means better only for the top few.

Progress is qualitative:

It’s about improving the quality of life for individuals and communities. It’s about creating purpose, opportunity, and a shared sense of well-being.

Growth is quantitative:

It’s about more—more buildings, more money, more population, more production. In today’s political and economic conversation, the emphasis has largely tilted toward growth, with progress becoming a secondary concern.

Growth as it’s now envisioned serves the machine:

The mega-municipality, the tax coffers, the swelling bureaucracy. Halifax’s drive to grow is driven by the need for higher tax revenues to fund the government itself, city services, and the cost and interest on the Big Box, Mega Project Pitches that make us “World Class”. But when growth happens without regard to the individual, it’s often just about expanding the city’s tax base and economic footprint. This kind of growth is about power—both governmental and corporate—and the size of the system, not the well-being of the people within it.

In this sense, Halifax’s unchecked expansion mirrors the phenomenon of GDP growth that doesn’t translate into better lives for individuals. The city’s economy may be growing, but is the quality of life for Haligonians improving at the same rate? No.

As GDP rises, GDP per capita—a better measure of individual prosperity—is declining. At latest measure it is now lower than it was ten years ago. If you feel worse off in spite of all the hype, it’s because by any rational measure you are. You are getting less and less back for your higher and higher taxes. This is the crux of the problem: the system grows, but the people in it do not reap the proportional rewards.

The GDP Illusion: Growing Bigger, Not Better

This illusion is most easily quantified in the divergence between total GDP and GDP per capita. When politicians or city planners tout Growth and the rise in GDP, they’re usually pointing to the overall economic activity: the sum total of goods produced, buildings constructed, and services rendered. The growth of the system. GDP growth also includes the money we spend on homeless encampments, extra law enforcement, emergency services, more prison cells, and all the costs of the mess we’ve made. Our provincial productivity is among the lowest in the Western World. GDP and Growth without prosperity obscure the real story. A rising GDP can mask growing inequality, where the benefits of economic activity are concentrated in fewer hands. While the city may be getting “richer,” its residents are not experiencing the same lift.

In Halifax, a booming real estate market might push GDP higher, but if wages aren’t rising alongside housing costs, then the average person is worse off. This is where the mantra of “growth” falls short: it can lead to the misconception that more buildings, more development, and more economic activity automatically equate to prosperity for everyone. But that’s not true if the benefits of growth aren’t shared.

Right-Sizing: From Growth to Progress

In a world of limited resources, cities need to think less about growing bigger and more about growing better. Right-sizing means understanding the city’s true capacity—not just in terms of infrastructure, but in terms of niceness, beauty, and care… for everything.

Beauty

Beauty is the greatest, longest-term, and most sustainable creator of wealth, happiness, and prosperity in the history of the world.

Beauty, for centuries, was seen as the highest expression of truth and harmony, from the Greeks’ pursuit of ideal forms to the Renaissance masters’ celebration of balance and proportion. Philosophers like Plato and artists like Michelangelo popularized the idea that beauty was intrinsic to goodness and order, shaping societies and inspiring awe. But around 100 years ago, as modernism took over, beauty was sidelined in favor of functionality, efficiency, and the “new.” Artists and architects, rebelling against tradition, embraced the abstract, industrial, and often ugly, seeing beauty as outdated. The quest for technological rather than human progress overshadowed the timeless value of beauty, leaving us with soulless buildings and art that shocked rather than uplifted, and sought fame rather than giving peace.

Beauty may seem like a frill, something old-fashioned and extra. It’s not. It’s something we and the world need. It’s something we must return to. Growth is the logic of cancer. Beauty is the world and all things in it finding their balance.

Instead of endlessly expanding the urban footprint, Halifax should focus on progress: improving public services, creating affordable housing, preserving cultural heritage, and ensuring that growth enhances rather than erodes the quality of life for its residents.

Right-sizing also means acknowledging that scarcity is real. This is true in terms of land, infrastructure, and even social capital. The more a city stretches itself, the harder it becomes to meet everyone’s needs. In this context, focusing on sustainable, smart growth—where development is done with an eye toward the long-term well-being of all citizens, rather than the short-term gains of developers—is key.

A true vision of progress would balance development with the human scale: investing in beautiful communities, fostering high-quality public spaces, and creating opportunities for meaningful work that connects people to their city, others around them, and the natural world beyond. Halifax, like many cities, needs a more human approach, one that measures success not in GDP alone, but in how well it serves its people. It’s about moving away from growth for growth’s sake and towards a model of urban development that respects limits and celebrates and values quality of life.

Toward a Human-Centered Vision for Halifax

If we apply the principle that “all lines are curves” to the current politics of Halifax, it becomes clear that unchecked growth will lead to diminishing returns. Beyond a certain point, which we have surely passed, more buildings, more development, and more economic activity won’t lead to a better city—they’ll lead to congestion, unaffordability, and a loss of the very things that make Halifax unique: its history, its culture, and its livability.

The conversation must shift back to people, to progress as a qualitative measure of success. Halifax’s future should not be defined by how many cranes there are, how many skyscrapers it can build or how fast its GDP can rise, but by how well it balances growth with the needs of its residents. In the end, the city’s success will be measured not by how big it gets, but by how good it becomes at serving the people who call it home.

Small Towns, Big Returns - Part IV

Imagine, instead of constantly pushing the limits of vertical growth in Halifax—taller buildings, denser populations, more strained infrastructure—we redirected our efforts toward something more sustainable, more human-scaled.