O Canada, Where Art Thou?

More Than a Cape for Hockey Fans – Why it’s time to stop treating our flag as just game-day gear.

Red, White, and Blah – The quiet crisis of national pride in the True North.

Most Canadians don’t know it, but February 15 is Flag Day. This year, it marks the 60th anniversary of the red-and-white maple leaf flag—our flag. It’s like Valentine’s Day, except for the flag. That’s worth celebrating, or at least, worth talking about. But as with all things Canadian, our national symbols tend to be wrapped in a peculiar sort of shyness. We’re a country that apologizes before we demand respect, that mumbles about patriotism while avoiding eye contact, and that generally treats the idea of national pride like an embarrassment. Sixty years later, do we even know what our flag stands for?

A flag should unite. In Canada, it often just reminds us how divided we are about ourselves. So why should this Flag Day be different?

For one thing, it arrives at a moment when even our former prime ministers are urging us to show the flag, and not just because of nostalgia or civic duty, but as a reaction to the latest provocations from the United States. Apparently, it takes Donald Trump to remind Canadians that they have a country worth standing up for. That’s the kind of patriotism we do best: reluctant, reactive, and a little bit anxious.

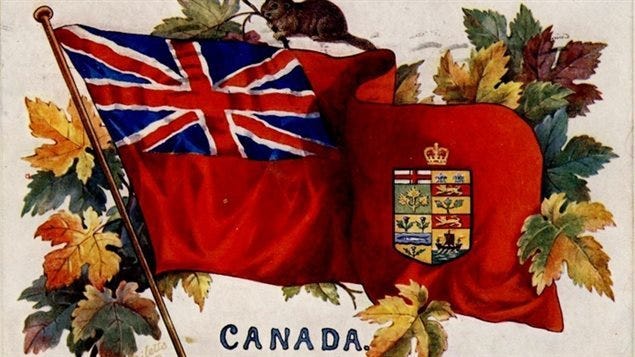

It wasn’t always this way. Before 1965, Canada didn’t even have a flag of its own. We borrowed Britain’s. The Red Ensign fluttered from our ships and buildings, a colonial hand-me-down that served well enough but never quite captured the idea of Canada as an independent nation. The battle over replacing it was fierce. Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson pushed for a flag that would belong to Canada alone, something that wouldn’t remind French Canadians of British rule or force new immigrants to salute a past that wasn’t theirs. The debate was ugly, prolonged, and deeply Canadian in its discomfort with making big decisions, though the classic heritage minute somehow finds a happy story and a hero in it all.

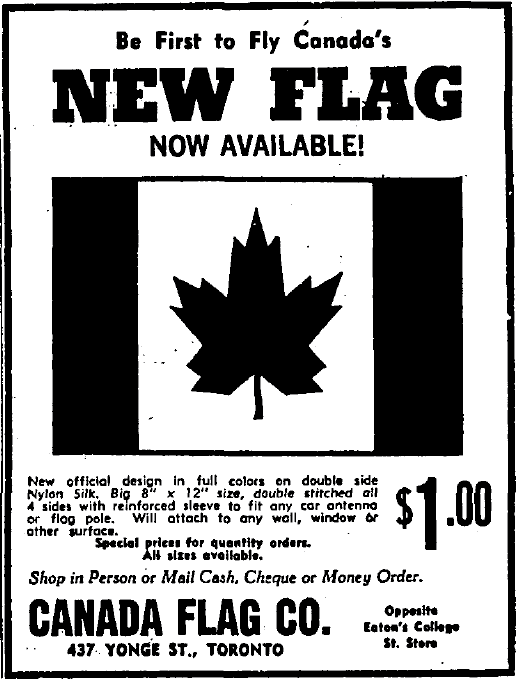

Historian Rick Archbold described the debate as “among the ugliest in the House of Commons history.” By that he meant it brought to a head many of the issues of empire, race, and rights Canada was confronting in the 1960’s. The new flag, designed by George Stanley with final touches by graphic artist Jacques Saint-Cyr, was approved on 15 December 1964 by a vote of 163 to 78. The royal proclamation was signed by Queen Elizabeth II on 28 January 1965. The national flag was officially unfurled on 15 February 1965. In 1996, February 15 was declared an annual National Flag of Canada Day.

When the maple leaf finally took its place on February 15, 1965, it was a moment of forced patriotism. The country had, at last, put up a sign that said: "This is who we are." We had to grow into it and furnish it with meaning, purpose, and history.

Not everyone was onboard. I can well remember at least ten years later in 1975 Red Ensigns on barns and houses all through the counties of Nova Scotia.

And here we are, sixty years later, still fidgeting with our national identity, still reluctant to embrace the very things that define a country: citizenship, participation, and belonging. At some level, we’re still in denial. We rank among the lowest in voter turnout among developed nations. Political party memberships are anemic. Even the idea of identifying as a "Canadian" first—before a hyphen or a region or a grievance—feels suspect in certain circles. We act as if patriotism is something to be phshaa’d.

And there’s some reason for that. Canada is the child of battling empires, a teenager rebelling against the perceived flaws, faults, and foibles, of the parents.

We do see the symbolism. Like John Prine we’re all to comfortable with seeing the flag as a symbol of violence, oppression, and folly. Any Canadian can plumb the depths of Prine’s metaphor. It’s the good part we have trouble with.

And then there’s America.

In the United States, the flag is everywhere. On houses, on trucks, on T-shirts, in courtroom pledges, at sports events. That level of flag-waving would make most Canadians turn red, white, and blue with shame, but there’s something to be said for at least being willing to acknowledge one’s own nation with clear minded confidence and purpose. The American flag is a statement. The Canadian flag, for too many, feels like a badge that you might get in elementary that everyone gets for participating, whether they really did or not.

America, The Symbols and the Thing Itself

But there is a problem with flags in America, and it goes back to Canada’s parent problem again. A flag is a symbol. A piece of cloth, bright with color, fluttering in the wind. But a symbol only matters if people remember what it stands for and actively search for its meaning, not up on the pole, but inside of them.

In America, surveys reveal that many citizens cannot explain the history behind their own flag, or the personal meaning of other national emblems. The bald eagle, the Liberty Bell, the Fourth of July—once living representations of ideals—have been reduced to background banners. The firework explode in the distance, everyone oohs and awws, but no one quietly contemplates what it must have been like for Francis Ford Keys to stand on the deck of the British Frigate that has captured him on its way to burn and pilage the Washington DC in October 1814 and see the Cosgroves rockets, the first military rockets used in battle launched toward Baltimore, as he described in his note that became is song - The Star Spangeled Banner.

Here We Are Now Entertain Us

This is the slow erosion of civic memory, a quiet decay masked in pageantry. The anthem still plays, hands still go over hearts, but the meaning fades, especially inside the citizen. A country whose citizens forget the substance behind its symbols drifts into spectacle—loud, colorful, but ultimately empty. Patriotism becomes performative, history turns into marketing, and democracy reduces to branding. People defend symbols with passion yet cannot articulate what they symbolize.

This isn’t just an American problem. It’s a human problem. Institutions, traditions, and even faiths fall into this same pattern—where the outer forms persist long after the meaning has slipped away. Yes, I’m looking at you Christian Church! Freemasonry warns of this in its own rituals, cautioning against mistaking the tool for the truth, the signpost for the destination.

Those people and institutions that have come to mistake the symbol for the thing symbolized are sleeping through life. Their only concern about the world is that it stay in one piece during their own lifetime. They regard their great good fortune in existing at this place and time rather than any other in history, not as a challenge to get close to the real problems of the world, but as proof of the correctness of everything they think, do, and say. The specticale is sufficient if it is bombastic enough to entertain them in the moment.

Talk of the legacy of the past or of human destiny leaves them cold.

To struggle against these enemies, and against apathy and mediocrity, is to find the purpose of life.

The 30th degree, Knight Kadosh, of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry emphasizes the importance of understanding Masonic symbols as representations of deeper truths, cautioning against mistaking the symbols themselves for the truths they signify. In his companion book to the degrees, Morals and Dogma, Albert Pike writes:

"Symbols were the almost universal language of ancient theology. All religious expression was symbolism. The early nations received the primitive idea, embodied in a simple mode, which subsequent ages amplified, adorned, and obscured with a multitude of accessories, until the true principle was wholly concealed. The Hebrew writings show that symbolism was the mode of teaching adopted by the Hebrews. The mode of teaching by symbols is older than even the Brahminical mysteries. In the Hebrew writings, the mode of teaching by allegory is adopted alike in prose and poetry. The earliest instructors of mankind not only expressed their lessons in symbols, but also invented a great many signs and fables, whose meaning was known only to the initiated. The mysteries were a series of symbols; and the explanations of them were symbols themselves. The hieroglyphics of Egypt, the fables of the Greeks, the mythology of the Druids, were all symbolic. The ancient symbols and fables have become the nursery tales of the present day, and are regarded as fictions, though they conceal meanings still."

Pike underscores that these symbols and allegories were designed to convey profound philosophical and moral lessons, and that their true purpose is to guide initiates toward enlightenment and self-improvement. He cautions that over time, the original meanings of these symbols can become obscured or lost, leading individuals to focus on the symbols themselves rather than the deeper truths they represent. This teaching aligns with the broader Masonic principle that the external forms and rituals are means to internal growth and should not be confused with the ultimate truths they aim to illustrate.

A nation that loses its grip on its founding principles—liberty, responsibility, self-governance—soon finds itself waving a flag with no real understanding of the republic it represents. And when symbols replace substance of the thing symbolized, when the allusion is mistaken for the thing itself, the decline isn’t just civic. It’s existential.

But maybe the true lesson of Flag Day is this: a flag is not just a piece of fabric. It is a mirror. It shows us what we are willing to stand for, or in Canada’s case, whether we’re willing to stand at all. If the sight of the maple leaf can still inspire, if it can still unite, then maybe there is hope that we can find a way to embrace not just the flag itself, but the country it represents.

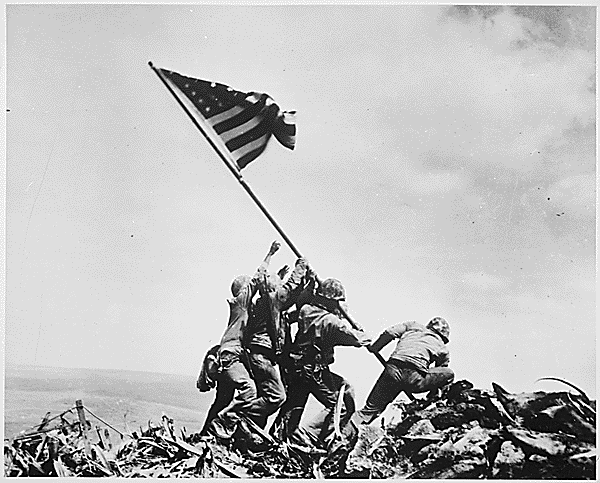

Maybe our flag is too clean. The red and white too crisp, too unsullied, as if it has never faced the wind and the rain, never been dragged through the mud of history. Maybe that’s part of the problem. The stars and stripes of Betsy Ross flew through revolution, tattered but defiant. The flag over Iwo Jima was raised on a battlefield, stained with the struggle that gave it meaning. But ours? It is bright, immaculate, almost untouched—as if we have kept it safe but at the cost of forgetting what it should endure. A flag should bear the marks of the nation it represents, should carry the weight of its struggles and triumphs. Perhaps if our Maple Leaf were a little more frayed at the edges, we would remember that a country, like its people, is made strong not by its perfection, but by what it has survived.

In my view, no system of understanding teaches more about the workings of the government of people than Freemasonry. They do it through the language of symbols. Here’s the most crucial point. I’ll quote the point made in Morals and Dogma from the 30th degree of The Scottish Rite of Freemasonry.

WE often profit more by our enemies than by our friends. "We support ourselves only on that which resists," and owe our success to opposition. The best friends of Masonry in America were the Anti-Masons of 1826, and at the same time they were its worst enemies. Men are but the automata of Providence, and it uses the demagogue, the fanatic, and the knave, a common trinity in Republics, as its tools and instruments to effect that of which they do not dream, and which they imagine themselves commissioned to prevent.

In his commentary on this degree, Pike cautions against the error of mistaking symbols for the truths they represent, a misstep that can lead to dogmatism and the loss of deeper understanding. He underscores that symbols are tools to convey profound philosophical and moral lessons, and that their true purpose is to guide initiates toward enlightenment and self-improvement. This teaching aligns with the broader Masonic principle that the external forms and rituals are means to internal growth and should not be confused with the ultimate truths they aim to illustrate.

So this year, maybe go ahead and fly the flag with hand on heart for a reason. Not in defiance of Trump, or as some reaction to an insult from abroad, but simply as a reminder to the world that lives inside you of your lifelong struggle to find a more noble and glorious purpose than simply just being; to spend life’s fleeting moment searching for, as Charles Eisenstein wrote in his resonantly titled 2013 book… The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible. Because our hearts live there in that imagined world of symbols, where our heart and hope, concerned for the rights of unborn legions that will enable the world itself to become connected and whole, is symbolized by the flag. Because it means something—even if we’re still figuring out what.

https://snyder.substack.com/p/crossing-a-line?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email