No More Hyphenated Canadians

Just step away from the grievance, put down the hyphen and everything is going to be fine. Maybe not exactly as you or I personally want it. But with a future filled with opportunity and promise.

If we believe in building a better Canada, we must give up something we’ve lived with for a long time. Not land, not language, not liberty—but the hyphen. We must stop being hyphenated Canadians. Because no national project can succeed when its citizens are more loyal to their fragments than to the whole.

The hyphen doesn’t hold us together. It separates us into census blocks and cultural silos. It preserves difference, but at the cost of unity. We drift—from pluralism into tribalism, from unity into entropy.

A NATION IS NOT A PATCHWORK OF EXCEPTIONS

The national project, if it is to be pursued further, requires cohesion. It requires belief in something larger than ourselves. A shared purpose, a single future, not a special or aggrieved past. A single and shared sense of duty to the unborn, the rising generation, and the shape of things to come.

This is why all successful nations—especially young ones—had founding creeds that superseded their internal divisions and looked to a shared future. Canada’s challenge today is not about remembering who we were in parts, but deciding who we want to be together.

Do we want to be a country that matters? A nation capable of building, defending, and bequeathing a future? Then we must choose to be Canadian, full stop.

What This Essay Is Not

Let’s get something out of the way.

This isn’t a rejection of culture, heritage, or where your people came from. It’s not American-style assimilation. And it’s definitely not a call for some beige, bureaucratic homogeneity where no one dances, cooks, or speaks differently.

My people? Highland Clearance Scots. Driven from their land and lives by an English empire, scattered across oceans, and told to start over where there was nothing and no one. It wasn’t even a war. Nothing so grand. Just murder, pillage, and domination. with no one to fight for us or even remember, outside a few families left on the shores of Nova Scotia. Like many who now call Canada home, our story includes exile, loss, and survival. And like many, I was raised to honour it. I do.

But honouring where we came from isn’t the same as deciding what kind of country we live in now. Or what this country should be. Let’s return to the home what has always been the domain of the home. Let’s get our half-remembered past out of government and citizenship.

This essay isn’t about forgetting our hyphenated history or homeland. It’s about asking what happens when the hyphen becomes the whole story—and all the hyphens become a picket fence that prevents us from imagining the future.

Culture belongs in our kitchens, our stories, our songs, our ceremonies, and cemeteries.

But citizenship belongs to Canada—or it starts to belong to no one.

Canada’s promise was always about building something bigger and better than where we came from. Something singular, unique in the world and history—for the future. The hyphen explains how we got here. Now it’s time to ask if it’s holding us back.

OK, let’s begin…

A NOTE ON PLURALISM

Canadian Pluralism says the hyphen is not a fracture, but a bridge. That recognizing many cultures within one nation doesn’t weaken the shared civic bond—it strengthens it. That pluralism, lived honestly and generously, is the true strength of Canada. And that asking people to drop their hyphens risks erasing the very voices we’ve only just begun to hear—especially Indigenous ones.

It says that no single word can fully contain what it means to be Canadian.

But this essay isn’t a rejection of culture, or of history, or of identity. It’s a question. A hard one.

It asks whether our current version of pluralism is doing what we hoped. Whether the constant deferral to difference is building something shared—or just something complicated. Whether, in our effort to hold space for every story past, we’ve lost the plot of our own future.

A country is not a census. It’s not a festival. It’s not a grant application. It’s a thing you believe in, fight for, and even love unconditionally.

The hyphen helped many people find their place here.

But now we ask: What place will we share in the future, and how do we get there together?

THE MATH OF THE HYPHEN

When you hyphenate your citizenship, you're not adding. You're dividing. You're suggesting that Canada is secondary to something else. Or you are claiming you are something more special, better than, different from the whole. You're turning the idea of Canada from a unifying identity into a wrapper for private grievance. And so we drift—from pluralism into tribalism, from unity into entropy.

HOW DID WE GET HERE - UNIQUE AMONG NATIONS AND HISTORY?

Before “diversity” became a virtue and long before it became an industry—the question of what kind of Canadian you were had a much sharper edge.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as immigration reshaped the young Dominion, the term hyphenated Canadian began to appear in newspapers and parliamentary speeches. It was a shorthand—at first neutral—for people who identified by both their origin and their adopted nationality: Scottish-Canadians, Irish-Canadians, French-Canadians, Ukrainian-Canadians, and so on.

The real firestorm came during the First World War. Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden, faced enormous resistance from French-Canadians—led by Henri Bourassa—over conscription. Bourassa argued that Canada should not be dragged into Britain's imperial wars, and he made the case for a bilingual, bicultural Canada rooted in mutual respect… that exempted French-Canadians from national service. The irony was that Fench-Canadians did not want to go fight in the fields of France and Belgium. But for Borden, Bourassa’s stance was evidence of the dangers of hyphenation: to be French-Canadian was, in this view, to be not-quite-Canadian.

DON’T TALK ABOUT THE WAR

This was a hard rule when I was a kid. The books about the First World War in my Grandmother’s house were hidden in a chest in the barn. My grandfather took his life in his hands to show my brother and me when we were kids. I can still smell the paper-dry musty perfume that blew into my face with the turn of every page. Politics, race, religion, Israel, violence, and war were only discussed out in the barn. It’s funny now to think how much we learned there and how much is still central to today’s wild world.

With regard to hyphen… French-Canadians did not feel kinship with Republican, modern France. Their world—rural, Catholic, nationalist, and insular—was shaped not by the France of the Enlightenment or the Revolution, but by a long memory of abandonment. France had ceded them to the British in 1763 and never looked back.

To many Québécois in 1917, “France” was just another foreign power. And “Canada”—as defined by English Protestants—was not theirs either. They were French-Canadian. The hyphen was not a bridge. It was a border.

For English Canada, the refusal of Quebec to fight in France confirmed their worst fears: that hyphenated Canadians were half-loyal at best. This helped cement a long-standing suspicion of “dual loyalties” that continues, in new forms, to this day.

But from the perspective of many French-Canadians, being forced to fight in a war they did not choose, for a crown they did not revere, in a land that had long ago abandoned them, was the real betrayal.

In Canada, this became not just about assimilation but about the architecture of the country itself. The English imagined a dominion of loyal subjects. The French imagined a partnership of founding peoples. Everyone else—from Jewish immigrants in Montreal to German fishermen in Nova Scotia, and Asians in BC—was expected to pick a side.

The issue didn’t fade. In fact, it hardened as English-French tensions grew through the 20th century. Quebec nationalism pushed “French-Canadian” into “Québécois.” The Quiet Revolution made cultural identity a demand, not a description. Meanwhile, multiculturalism—enshrined in 1971 under Trudeau the First—was pitched as a new Canadian invention: instead of one culture or two, there would be many. All equal. All Canadian.

But not everyone bought it completely.

Even Pierre Trudeau famously insisted on a "just society"—but he also loathed the idea of tribalism. He warned against "ethnic nationalism" and envisioned citizenship as something civic and shared. Trudeau’s Canada didn’t want hyphens. It wanted intellectualism in a kind of childish way.

Still, his policies encouraged the use of hyphens as public identity. Ethnic groups were now “communities.” Their leaders were consulted, funded, celebrated. Over time, this became a currency in politics—especially in urban ridings. Politicians learned to court Chinese-Canadians, Sikh-Canadians, Somali-Canadians—not just as voters, but as voting blocs.

And now here we are.

We’ve never forged a single civic story powerful enough to eclipse the hyphen. And in that vacuum, the fragments have multiplied.

We’re on a search for a story strong enough to unite a country of many nations, many languages, many grievances… and one passport.

In theory:

America assimilates: “You become American.”

Canada accommodates: “You stay who you are — just also Canadian.”

The problem? The American model can erase difference.

The Canadian one can preserve it so fiercely that it crowds out shared citizenship.

This is what this essay about Canada is reacting to — not to immigration, not to diversity, but to the hollowing out of the common.

It’s not about forcing sameness. It’s about insisting that something must be shared. A national core. A civic allegiance. A citizenship that doesn’t change depending on where your ancestors were born or the order in which you arrived.

THE NATIONAL PROJECT REQUIRES FOCUS

The hyphen is a kind of flag. A whisper of dual citizenship in the soul. In times of peace, it feels harmless. But in times of war, crisis, change, or realignment, it becomes an enemy to all.

A national project requires cohesion. It requires belief in something larger than ourselves. A shared purpose, not a special or agrieved past. A single sense of duty to the unborn and the shape of things to come. This is why all successful nations, especially young ones, had founding creeds that superseded their internal divisions. Canada’s challenge today is not about remembering who we were in parts, but deciding who we want to be together.

Do we want to be a country that matters? A nation capable of building, defending, and bequeathing a future? Then we must choose to be Canadian, full stop.

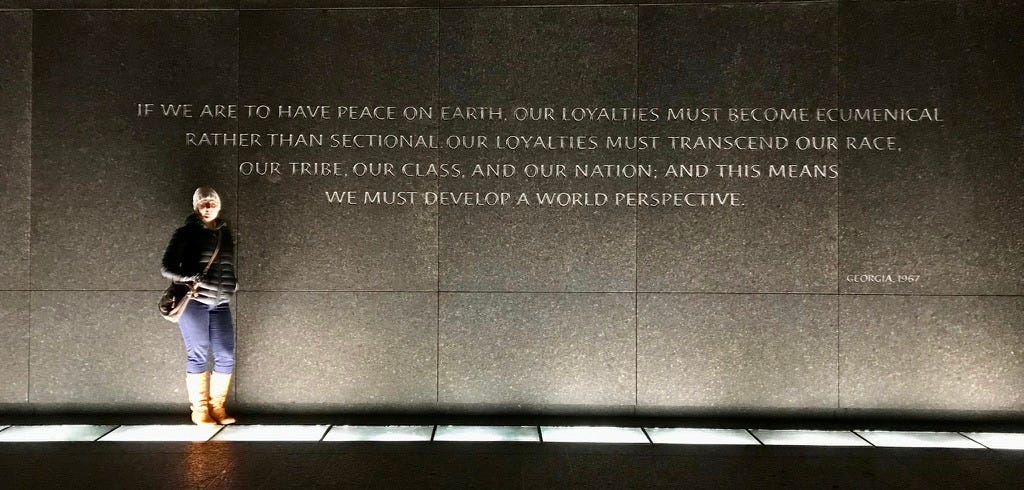

THE PRICE OF AN ECUMENICAL FUTURE

There is no future in fragments. No peace in pluralism that lacks purpose.

Who inherits Canada if nobody believes in Canada? Who sacrifices for it, if their real allegiance is elsewhere or only inside themselves? Who builds when all they’re told is to deconstruct?

Originally, ecumenical referred to efforts within Christianity to bridge denominational divides—Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox—focusing on what unites believers rather than what separates them. But over time, the term broadened. Today, ecumenical in a secular or social context, means:

Seeking unity across difference without erasing distinct identities.

In the hyphenated Canadian context, ecumenical thinking asks people to rise above faction, tribe, and inherited loyalties—not by denying them, but by not letting them define the whole of a person. It suggests a shared citizenship, a common purpose, a spiritual or civic brotherhood that supersedes ethnicity, region, tribe, or grievance.

An “ecumenical vision of Canada,” is calling for a country where French, Chinese, Single, Gay, Senior, Unemployed, Liberal, Indigenous, or African Canadians don’t have to deny who they are—but also don’t have to hyphenate it to be accepted as fully Canadian and get their fair shore.

It's about communion over fragmentation.

Or to put it more sharply: ecumenical is what happens when you let go of the hyphen, not the heritage.

YOU CANNOT LOVE YOUR COUNTRY IN PARTS

To believe in Canada is to love the whole of it. Hyphens are fences, not bridges. They preserve difference but prevent unity. They’re perfect for sorting census forms, terrible for building a national project.

THE CALL TO THE RISING GENERATION

Multiculturalism does not just dissolve into petty grievances. It’s suicidal for a nation. The nation is a short-lived affair, and there is no recognizable Canada worth caring about if we don’t have a shared vision of a nation. By 2100, in 75 short years, every one of us reading this will be dead. Mostly forgotten. And if we leave nothing behind but tax gripes, self-definition, and differences, there will be no Canada to inherit.

A national project—any national project—demands unity, not equity scores. Shared burdens, not bespoke rewards. A vision for the future, not an interest group that’s won its case and gotten its special recognition. If Canada is to be anything more than a hotel lobby with a complaint department, we have to give up the hyphen. We have to dedicate ourselves not to our tribe, not to our type, but to the Dominion.

The next generation must not be taught to be Something-Canadians. They must be taught to be Canadian. Period. We are either going to be a nation of the future or we are going to be nothing. Their loyalty must be to the Dominion, not as a colonial relic, but as a covenant to build a better future. An agreement to take up the task of nation-building: with seriousness, with love, and with pride.

The goal is not erasure. The goal is inheritance. The cultures that thrive in Canada should be those that contribute to Canada. Our cultural differences should season our citizenship, not override it. They are important only to the extent that they clearly and quantifiably contribute to the future. You can celebrate your roots without denying our greater purpose. I can be a maudlin fool for my family and Highland heritage, but it has no place in the affairs of the nation, and it becomes a genuine distraction if I insist the future itself must somehow mollycoddle the identities of past ancestors.

THE END OF THE HYPHEN IS THE BEGINNING OF PURPOSE

To remove the hyphen is not to erase history. It is to make history. It is to claim your place in the long story of a real country. A story yet to be written about a country with borders, beliefs, burdens, and beauty. A country that matters. A country that endures.

So choose: Your tribe or your nation.

Because if you can’t give up the hyphen, you’ve already given up on the country.

POST SCRIPT

Among the greatest band leaders of all time, Benny Goodman—The King of Swing—ran one of the most diverse, disciplined, and long-lasting big bands in history. Black and white players. Jewish, Italian, Protestant, Catholic. From Gene Krupa to Lionel Hampton, Teddy Wilson to Harry James. In an era when segregation was law in much of the U.S., Goodman didn’t just ignore the hyphens—he blew past them beating eight to the bar.

He ran a tight band. No special treatment. No solo just because of your surname or skin tone. You either played your part—or you didn’t play at all.

And while he almost never sang, there’s this one tune—“It’s Gotta Be This or That”—where Benny steps up to the mic with a playful, crooning ultimatum:

If it ain't dry, it's wet

If you ain't got, you get

If it ain't gross, it's net

It’s Gotta be this or that

And maybe that’s our moment now.

The hyphen says: You can be a little of this, a little of that, neither here nor there.

But the band can’t swing if everyone’s on a different chart.

So maybe it’s time to drop the hyphen—not because we want less diversity, but because we want more harmony.

More common purpose.

More music.

Not this and that.

This or that.

Canada—unhyphenated—might be a harder tune to play.

But if we can lock in, keep time, and listen to each other—

It might swing.

Or we could take the idea to space.

I’m jumping into deep and rough waters here. Few TV series stories have been more discussed, sliced, diced, and dissected than Star Trek.

It began in the original series, where diversity was radical for the time, but incidental to the mission.

Uhura was Black. Sulu was Japanese. Chekov was Russian — during the Cold War, no less. Spock wasn’t even human. And yet, nobody got a special hyphen. Nobody asked, “As a Vulcan-Human hybrid, how do you feel about this warp core failure?”

They had jobs to do. The bridge had a mission. And when Captain Kirk barked orders, they weren’t filtered through a council of grievances — they were followed, debated, refined, and executed as a team. Not because they all came from the same background, but because they shared a purpose.

That’s the dream, right?

A Canada where your story matters — but your allegiance matters more.

Where your culture is respected — and your citizenship is non-negotiable.

Where we’re not forever slicing ourselves into smaller sub-identities, but pointing the whole ship in one direction and boldly going.

No hyphens on the bridge. Just the Federation — flawed, idealistic, changing, and still the best idea anyone’s had for keeping the peace in a galaxy of difference.

I guess the other thing I might point you to is the octopus. It has, essentially, 9 brains. The central nervous system, can, but does not always, control the independently "brained" arms (all 8 of them). This makes the arms much faster to react to outside threats and opportunities.

Now, Heinlein would tell you that, "a committee is a creature with 6 or more limbs and no brain," but what if it's the opposite? What if a country can be something with millions of brains controlling a multiplicity of limbs? What if we're (socially) evolving greater independence from centralized authority in general? So instead of a king or oligarchs we're headed towards true democratic action directly by the individual. So, "why do we currently have so much fascism?" you might ask. It's a good question. I suspect it's because evolution seems rarely to be a straight line. Instead, it seems a pretty bumpy road with lots of off-ramps.

Here, I think, we're diametrically opposed.

Consider regular steel vs its doped counterpart. Doping increases certain properties, by including the inherently different material you can increase thermal stability, compression resistance, shearing resistance, etc. Rather than having a uniform, ordered structure the elements which are different allow everything from flexibility to resistance against various forms of strain. You see the same basic forces at work in compound and nano material structures. Where layers ordered differently (often perpendicular to other layers) or tiny structural differences can impart all sorts of properties, up to and including invisibility to certain wavelengths. Similarly fabrics, woven with patterns of colour or texture can be more pleasing to the eye than simple white muslin (although that can be pleasing too and often serves as a base for finer materials).

Part of what "hyphenated" Canadians can provide is error correction. I think you'd agree that some of what we have at the beginning of this century is outdated accumulated social cruft. We need to toss some of the old ideas we had into the bin of history as outmoded, inherently preventing us from moving forward. I think we have new social paradigms forming, but not yet stabilized. I see the inherent weaknesses of slower communication, high latency social connection and hidden, proprietary or obscured social information of our era being replaced, but not yet at the level of true interoperable structure. Social media has been, at least in part, an experiment where most of the players fell by the wayside but the structures taking their place are also not yet fully formed or useful. And TikTok doesn't yet have political sway (although something like it might). Right now it's more like the interpretive modern dance model of modern discourse, but it will evolve.

That's where we are though, in the space where new modes of communication and understanding are forming. The old paradigms are shifting and becoming obsolete. It's part of why the structures we're used to are crumbling and there's so much general anxiety. But the answer isn't to hold on to the old structures at all cost. It's to navigate the new waters and explore the aftermath of current tidal wave we're not even at the crest of yet.