I'm Offended!

As I come up onto my first anniversary on Substack I look back and see a lot of offensive stuff. Maybe we should bring back dueling.

Coming up on my first anniversary writing long-form on Substack, I can see how large a portion of the things I’ve written have been inspired by some offense I’ve taken to this or that. I’m not the only one. And it’s not just Substack. It’s all media and social media.

In a world of mass communication, outrage has been industrialized, monetized, and commoditized.

A significant portion of Substack articles—perhaps a plurality—are inspired by offense in some form. Whether it’s personal offense, ideological offense, cultural offense, or moral indignation, a great deal of writing stems from the feeling that something is wrong and must be addressed. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing; offense, after all, is a reaction to perceived injustice, hypocrisy, or ignorance, and it often fuels sharp, engaging writing ( I hope ).

We might frame this prevalence of offense-driven writing as the result of:

The Attention Economy – Outrage drives engagement.

The Digital Age of Identity – People write to defend their personal or political tribe.

The Collapse of Traditional Media Gatekeepers – Substack allows voices that once had to play by newsroom rules to express unchecked opinions.

I love four-quadrant analysis. Let’s start with making up a “Spectrum of Offense”… I’m just making that up, we may come up with a better name later. The idea is to hope that offense, however high in quantity, also has a quality aspect that we can measure and understand.

To better understand this phenomenon, let’s map offense-driven Substack writing into four quadrants, based on two key factors:

Is the offense personal or political? – Does the writer focus on personal grievances and experiences, or are they tackling broader societal and ideological issues?

Is the approach constructive or destructive? – Does the writer use offense as a means to build and propose solutions, or is it pure venting and destruction?

This allows us to see where different writers and our own works of words fall—whether they are thoughtful critics, righteous warriors, chronic complainers, or rabble-rousers.

1. Thoughtful Critics (Personal & Constructive)

These writers use personal experiences of offense to explore bigger themes in a meaningful way. They take something that happened to them, or something they’ve noticed and turn it into wisdom, analysis, or a call for change. Their work is often introspective, philosophical, or memoir-like, using storytelling to draw larger conclusions about society, human nature, or their industry.

Examples: Writers who analyze their own experiences with injustice, hypocrisy, or absurdity in a way that resonates universally. Think of a freelancer discussing the gig economy’s pitfalls, a disillusioned journalist breaking down media bias, or a former activist reconsidering their past beliefs.

Tone: Measured, thoughtful, personal, and engaging.

Impact: Encourages reflection, insight, and sometimes, meaningful change.

2. Righteous Warriors (Political & Constructive)

These are the writers who channel their offense into activism, argument, and persuasion. They see something broken in the world and aim to fix it. They can imagine more and better and are willing to work for it, or at least talk about it. Their writing is often ideological but well-reasoned, offering proposals, strategies, or frameworks for action.

Examples: Political essayists, reformers, and those pushing for legislative or cultural shifts. Think of a progressive journalist making a case for universal healthcare, a conservative outlining an argument against bureaucracy, or a local advocate calling for better urban planning.

Tone: Passionate, strategic, persuasive, and sometimes moralizing or a little judgy.

Impact: Can lead to real-world change, influencing political and cultural discourse.

3. Chronic Complainers (Personal & Destructive)

These writers take personal offense and do little more than stew in it. Their writing tends to be bitter, self-pitying, or resentful, often focused on perceived slights, injustices, or their own lack of recognition. Instead of analyzing or learning from their experiences, they vent, sometimes amusingly, most times not.

Examples: The writer who constantly complains about their industry’s, group’s, and community’s gatekeepers. The ex-academic or professional who blames the system for their failures. The self-described ‘canceled’ writer who can’t move on.

Tone: Whiny, bitter, defensive, self-absorbed. Often blameful and sees enemies everywhere. Alcohol is often involved.

Impact: Limited, often repelling readers who tire of constant negativity. But they have some small complicit cheering section who tend to goad them on.

4. Rabble-Rousers (Political & Destructive)

These are the bomb-throwers. They write not to persuade but to enrage, provoke, and dominate the discourse. Their primary goal is to rally their ideological tribe against the ‘enemy,’ and offense is their currency.

Examples: Culture war instigators, hyper-partisan ideologues, conspiracy theorists, and those who thrive on outrage. Think of someone constantly bemoaning ‘the woke mob’ or, conversely, someone ranting about ‘fascist conservatives’ without offering anything constructive.

Tone: Aggressive, incendiary, divisive.

Impact: Generates clicks and tribal loyalty but rarely changes minds.

Why This Matters

Understanding these quadrants can help us be more discerning readers and writers. It forces us to ask: Where do we fit? Where do our favorite writers fit? Are we engaging in offense productively, or are we just feeding the noise?

The best writing—whether it begins in offense or not—transcends pure reaction. It moves beyond grievance to insight, beyond attack to synthesis. It offers perspective, especially new or different perspectives, solutions, and, at its best, a glimpse of the world as it could be.

In the end, my Substack is what I make of it. The question is: Do I want a better discourse, or just a louder one? Am I venting or synthesizing? Am I offering something or taking something? As they say in the horn section, “Am I sucking or blowing?”

Where do you land in most of your writing and reading?

How do you perceive THE BEE so far?

Taking Less Offense: The Liberation of Not Caring

On the other side of the equation, how much offense should we take to the concerns of the day? How much time does the average person spend being offended? Not just irritated or mildly put off, but deeply, truly, theatrically offended? The kind of offense that requires a social media post, a long grumbling essay (my specialty!), or a furious group chat? If you measured it in hours, what fraction of a life does it take up? And for what return?

Taking offense seems to function as a kind of currency in the modern age. It confers status, power, and attention. It provides a moral high ground, a sense of superiority, and, occasionally, material gain. In an economy where attention is the scarcest resource, being offended is a way to demand it. The people who shout the loudest tend to get the microphone, and outrage is a shortcut to the front of the line.

But where did this behavior come from? Was it always this way? And where is it going?

The Evolutionary Roots of Taking Offense

In small tribal groups like my ancestor’s Scottish Clans, taking offense likely served a practical function. It was kind of our thing - and I think still is. You will very seldom meet a family with more internal estrangements than one of Scottish heritage - or counterintuitively, ones with a more careful and quiet understanding of each other. Social cohesion required some level of mutual respect, and reacting strongly to insults or slights might have been necessary for survival. Being offended was a way of policing behavior and ensuring that group norms were followed. In that sense, offense was a survival mechanism—an evolutionary tool to maintain order.

Fast forward to today, and taking offense has morphed into something else entirely. In a world of mass communication, outrage has been industrialized. Instead of protecting the tribe, it often serves to fragment society into ever-smaller factions, each competing for the title of Most Aggrieved.

The Modern Economics of Outrage

Outrage sells. Media companies have known this forever—if it bleeds, it leads. Social media algorithms have optimized for it, boosting posts that generate anger and controversy because they keep people engaged. Activists, influencers, and public figures leverage it to build their brands and advance their causes. Entire careers are built on being professionally offended.

It makes a certain kind of sense. If attention is currency, then taking offense is a way to extract value. Claiming to be hurt, outraged, or oppressed can bring followers, book deals, speaking gigs, and political influence. It's a transaction: your outrage, monetized.

The Power of the Offended

There’s no denying that taking offense can be a potent tool. Historically, marginalized groups have used it to challenge genuine injustices. Civil rights movements, feminist activism, and labor movements all required a measure of collective offense to effect change.

But when does taking offense become counterproductive? When does it cease to be a tool for justice and instead turn into a form of social control, a way to silence dissent and enforce ideological conformity? When does the power of the offended become a tyranny of the perpetually aggrieved?

The Value of Imagination in Offense

At its best, we are offended because we have an imagination. We can imagine things differently than they are. We can imagine more and better. We can hold people to a higher standard. We can have expectations. This is good and it drives human progress and flourishing. But you can go too far with anything. There was a long era where offense led to dueling. It was an important tradition and part of the order of things until deep thinkers saw the damage it did and the moral problems it created. Maybe we've just taken offense too far and we're due for a new order where this modern version of dueling is put aside for the greater good.

Pistols at Dawn

There’s some weird connection between modern offense culture and dueling. Dueling in Nova Scotia, as in many places, was once the bloody punctuation mark at the end of high society disputes, a gentleman’s way of settling slights before breakfast with pistols at twenty paces. The province’s most famous affair of honor unfolded in 1819 when Richard John Uniacke Jr., the fiery son of the Attorney General, shot and killed William Bowie over an insult too grave to forgive. It was a clash of honor and hubris, fought on the misty shores of Point Pleasant (park). The younger Uniacke, well-connected and well-spoken, managed to escape serious punishment, but the duel sent ripples through the colony, setting the stage for the decline of the practice. By the mid-19th century, dueling was all but outlawed, seen as reckless rather than righteous, foolish rather than fearless. And yet, in an age where mere words now lead to social excommunication and offense, we might consider some of today’s faceless outrage as a kind of dueling.

Perhaps the lesson isn’t to bring back pistols at dawn but to recognize that the very notion of being offended - part of our darker heritage - is maybe something we can move beyond. Because it’s dumb.

The Liberation of Not Caring

There is an alternative. Not everything requires a reaction. Not every offhand remark is a personal attack. Not every differing opinion is an existential threat. Some things are just… things.

Choosing not to take offense can be oddly liberating. It frees up mental space, emotional energy, and time—three things in increasingly short supply. It also makes life more enjoyable. There is humor in absurdity as any existentialist master knows, but it’s hard to see it when you’re too busy being furious.

In classic Stoic style, You don’t have to turn everything into a problem. You can choose not to engage. You can shrug, roll your eyes, and move on. Stick to your knitting. Stay in your lane. Keep your eyes on the prize. And in doing so, you reclaim control over your own emotions. A seasoned Nova Scotia politician once told me, “John Wesley, you don’t have to swing at every pitch.”

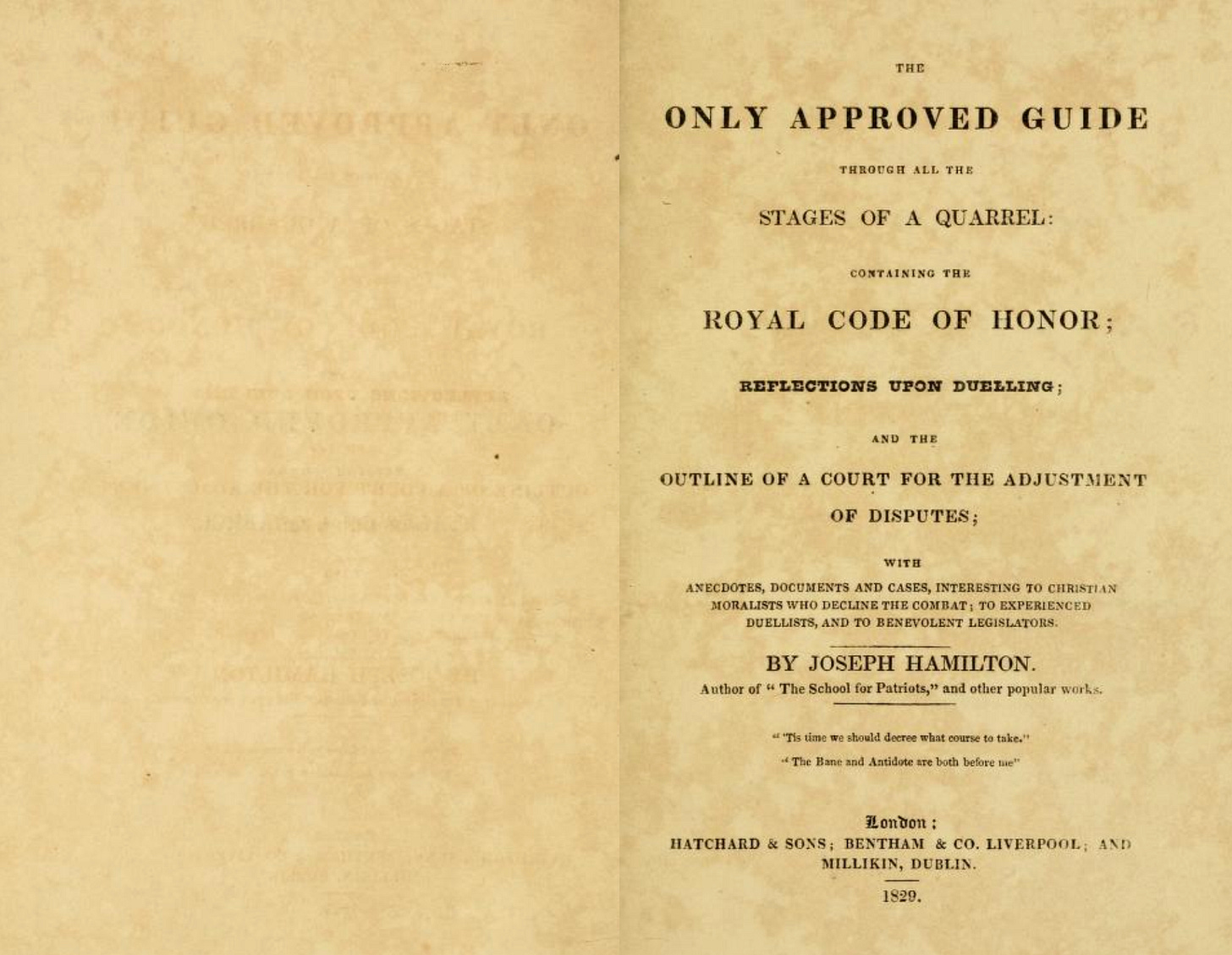

Maybe the most amazing lesson to come out of the age of dueling, and one that could be revised for the digital age is the Royal Code of Honour.

The 1829 Royal Code of Honour was a meticulously structured manual for resolving disputes among gentlemen, offering a framework that balanced personal dignity with measured response. In the digital age, where offense is often met with instant, unfiltered outrage, the Code’s emphasis on formalized escalation—requiring intermediaries, time for reflection, and clear thresholds for action—could serve as a guide for tempering reactionary behavior. Instead of impulsive social media pile-ons or cancel culture mobbing, a modern adaptation could encourage structured discourse: requiring offended parties to articulate their grievances directly, allowing time for response, and introducing mediators to defuse conflicts before they spiral. The Code’s insistence that not every slight warranted a duel—sometimes an apology sufficed—reminds us that not every offense today demands public shaming. In short, it offers a lesson in proportionality, restraint, and the idea that honor, not vengeance, should be the ultimate goal.

You are Being Robbed of Your Attention By Being Offended

In his new book, The Siren’s Call, Chris Hayes argues that we live in an attention economy and people, companies, and machines are working full time to make you offended to rob you of your attention, which is every bit as valuable as your labour, your creativity, of other efforts and resources.

His experience as a news show host has given him a certain perspective on how attention functions. Every moment of his work life revolves around answering the question of how he can capture attention. And it just so happens that the constant pursuit of others’ attention is no longer just for professionals like him. We’re all doing it.

It’s hidden in plain sight and it’s weird to think about.

The Future of Offense

Is all of this just a passing cultural phase, or are we stuck with an ever-ratcheting cycle of offense escalation? Will we reach a point of desensitization where taking offense loses its power, like a currency suffering from hyperinflation? Will we eventually rediscover the lost art of brushing things off? Or will we go back to dueling, which makes for surprisingly careful and polite social conversations?

If history is any guide, the pendulum will swing back. People grow tired of outrage. They seek meaning beyond perpetual grievance. They rediscover the joy of humor, of resilience, of letting things go. And maybe they start to remember that not everything is about them.

Taking offense is easy. Choosing not to is an art. And like all good art, it makes life better.

Hmmm,

What about a digital duelling system? For instance, we both get offended at each other. Rather than cancelling each other we each get a chance to "shoot" and whoever wins "silences" the other person (at least on that platform) for x number of (minutes, days, whatever). Perhaps there's even a chance for a "mortal wound" such that if the "shot" is good enough then forevermore on the platform the person has to type their response in twice or the comments box takes longer to load or something. It seems to me gamification of systems is already occurring, why not make it official and (digitally only) bloody! You could add in stuff where your (and my) followers get to weigh in and tilt the scales, make "mortal wounds" more likely, etc. I mean, sure, it's ridiculous, but then much of human social structure is when you look at it closely.

I think your point about not reacting is great. I remember one teacher in high school saying something to classroom about sometimes not answering his phone, just because (he was busy with something else, he was going out, he just didn't feel like it, etc.). Best piece of advice I ever got from a teacher and pretty much the only thing that one said that ever stuck. Not only do I sometimes feel like we're all in a crowded amphitheater with someone constantly yelling "fire" or "the sky is falling" from the wings that we just have to ignore a good portion of it to get anything done. Hell, I do it myself whenever I get on my rants about the environment. To be fair, the environment is a really big ship and it'll take a long time and huge effort to "move" it to another course after hundreds of years of pollution and right now every indication is that we're just dawdling along headed straight for the bridge. Or worse, we're without power (political anyway) headed for the rocks. See? Don't you wish you had a duelling option right now?

The other part is, of course, marketing. Chris Hayes (former MSNBC host) had a good article in The Atlantic about how attention is a resource like the wind and you have to tack along it's edges to capture it properly (he does the metaphor better than I). But you raised the duelling code. I'm often fond of the naked, unadorned and unadulterated if it shows good work underneath, but there's something to be said for ceremony and costume too. Often times just forcing things along or deluging something can't have a good effect. In culture, ceremony and even costume (which, for these purposes would include any decoration or embellishment) can have the effect of slowing things down, making them more enjoyable or easier to appreciate than they would otherwise be with that efficient, but stripped down effect. Unfortunately, just like those formless glass boxes you so despise in architecture, everyone designing the internet is trying to maximize return while minimizing effort. Perhaps we need the opposite approach too. For instance, I often miss MySpace for the individuality it allowed its participants to create. With TikTok, X and Instagram you're really locked into their aesthetic and have little choice to make it your own. I mean, MySpace certainly wasn't perfect, but it did have that going for it.