The Halifax Peninsula today is a 3x7 km snapshot of what happens when planners pursue density without dignity. The result isn’t a city. It’s a slow-motion traffic jam parked on an almost island, where the dream of urban life has been reduced to hoping you can double-park long enough to unload your stuff.

What the heck happened?

Some of our local councilors like to say that during the war and the post-war baby boom, there were many more people living on the peninsula in Halifax than now. This line of talk is intended to justify the new urban and up high-density building ideology by implying that today the peninsula is underpopulated and that economic prosperity would come if we just had more people.

In shorthand, they argue that GROWTH = PROSPERITY, and that this is a linear mathematical equation where no matter what the starting point or end, adding more growth will always be better because it will always produce more prosperity.

The Real Equation

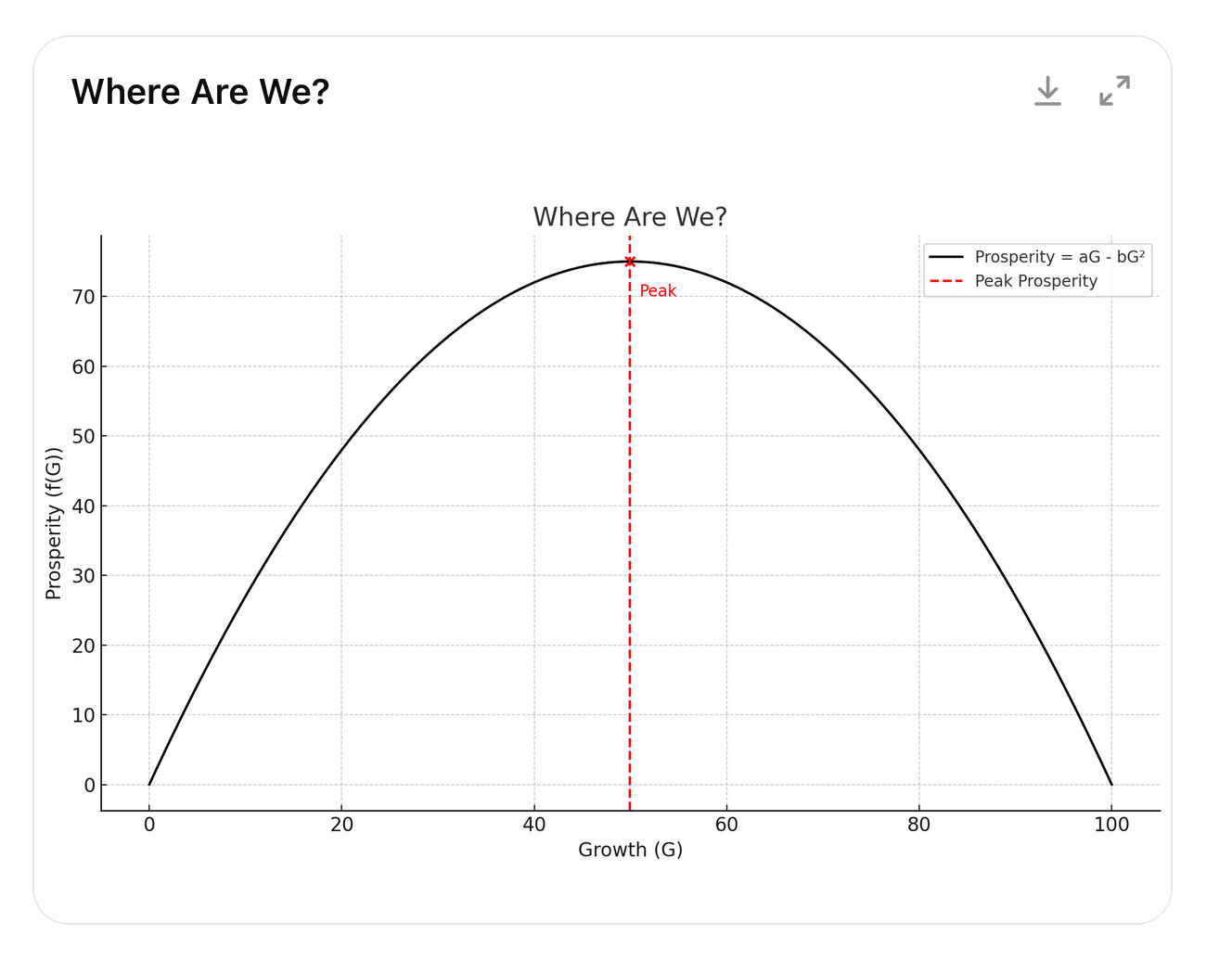

In reality, we would model the relationship this way:

This, you may remember from highschool math — how could you forget?!— is a quadratic equation that peaks at a certain level of growth and then declines—meaning some growth increases prosperity, but too much leads to congestion, unaffordability, and decline.

This curve is commonly used in economics to represent diminishing returns, optimal scale, or the Kuznets curve (e.g., inequality vs. development).

What It Leaves Out

This simple form doesn't account for:

Threshold effects (e.g., sudden collapses after too much growth)

Feedback loops (e.g., congestion increasing housing costs, which reduce household formation)

Multiple interacting variables (e.g., infrastructure, culture, governance quality)

Time lag (growth may initially look like prosperity before the costs show up)

In reality, prosperity might follow a skewed, asymmetric, or piecewise curve—or even something nonlinear and multi-peaked. But for storytelling, communication, and basic modeling and discussion, this is a better place to start than the straight line we’re using.

In Words and Pictures

In early stages, growth = shared infrastructure, more innovation, better services, and broader markets.

In middle stages, benefits slow—traffic increases, housing tightens, and social friction grows.

In late stages, more growth can reduce prosperity: rent inflation, gridlock, civic unrest, and institutional failure.

So, what is the right amount of growth? Do we need more? What will be the social, community, and economic return for more investment in growth on the peninsula? Here’s the curve titled "Where Are We?". It shows the classic inverted-U relationship between growth and prosperity. The red dashed line marks Peak Prosperity—the point at which more growth stops helping and starts hurting.

Is Halifax still climbing the curve, or have we already gone over the top?

Are we on the early side of the graph and moving toward “Family-friendly city” or have we passed peak prosperity and we’re tumbling toward “Unaffordable concrete canyon”?

Here’s the bad news of this essay. No one knows—except the people. There’s been no effort by city planning, municipal government, or even the province (though all of Nova Scotia has a horse in this race) to create any kind of working model to reasonably assess where we are on the curve between growth and prosperity.

Why is that important?

Because it’s like being lost in the woods. If you don’t know where you are, there’s no point in going anywhere. Every step might be taking you deeper into trouble. You could be one clearing from safety—or marching headlong into a swamp. And the more certain your guide sounds, the more worried you should be. Because certainty without orientation is how people disappear out there.

That’s where we are now: not too little growth, not too much—just totally unmoored from the question of what kind of city this is, what kind of future we want, and how we would even know if we were on the right path.

Why the Peninsula Doesn’t Fit the Linear Model

Space is fixed: You can’t grow horizontally. You must build up—or cram in. In some ways this 3 x 7 km almost island with only 4 main ways to get traffic on and off is the perfect case study for the importance of understanding the limits of healthy (as opposed to cancerous) growth in a community.

Infrastructure is aging and stressed: Water, sewage, roads, and power weren’t designed for this level of vertical density. The Armdale rotary, one of the key paths on and off Halifax, was originally designed for about 6,000 vehicles a day. Recent counts put that number at about 60,000.

Household composition has changed: The 1940s peninsula may have had more people per home, but they were families—now it's transient, low-attachment renters in micro-units.

Social capital is eroded: More units ≠ more community. You get density without cohesion.

The Flaw in “More = Better”

Treating growth like a one-way ratchet is like saying:

If one aspirin cures your headache, then 50 will fix your brain.

No. There’s an optimal dose. And past it, things fall apart.

I’m frustrated

Growth is not prosperity. It’s the symbol, not the thing symbolized. It's the fuel, not the fire. And like any fuel, too much at the wrong time can burn the whole house down. Halifax's Peninsula isn’t underpopulated—it’s overloaded. Not with people, but with an ideology that mistakes height for health, density for vitality, and concrete for community.

Meanwhile about 80% is totally unpopulated and there are more than 200 historic and new communities in the province starved for investment, infrastrucutre, and a little love form the provincial and federal coffers. Many of them, long in decline but still with the bones, the shape, of the kind of communities we’re all wishing for.

SIDEBAR: Here’s another way to look at it.

What if something bad happened?

So, are we better or worse off now than before? How resilient are we? This is the job of disaster management. Halifax has had one historic disaster and more than a few close calls. What would happen if it happened today? Are we better prepared to reduce, resist, or recover from a problem? Most of the world is much more resilient today than it was in the past. The death and injury toll from disasters today is only a small fraction of what it was 100 years ago. But in Halifax? Well… we have a problem. Remember that whole we’re almost an island thing, over stress and aging infrastructure and the urban and up development.

Let’s just hope everything goes perfect from this point on because experts say all this is a recipe for something terrible in an emergency situation.

Meanwhile, on the island of Halifax…

Stats Canada says the Peninsula's population grew in the war and post war boom to a high of 92,511 in 1961--and decreased thereafter. Most of this loss happened due to now discredited and misguided “Urban Renewal”. Africville is not the only displaced urban population. It edges beyond living memory now to recall that sites like Scotia Square and the Scotia Bank Centre were once living, high-density, residential communities. However, in recent years, the population has increased again. In 2016, the population was 63,210 people. Today, the population has increased back up to over 75,000 people--an increase of more than 15% from 2015.

But these raw numbers belie some defining demographic and geographic differences that anyone can see on the street today.

Families Are Being Squeezed Out

The urban planners promised walkability, live-work-play, and complete communities. What they delivered is a shoebox apartment with no storage, no parking, no playground, and a stroller-unfriendly streetscape. The result? Families move out. Students and singles move in. The city's demographic heart gets hollowed out.

Retail Collapse

One by one, Peninsula storefronts are shuttering. Not because people don’t want to shop local—but because it’s just too hard to park. Urban density that doesn’t invite consumer flow kills foot traffic and rewards delivery-based megacorporations.

The Wrong Kind of Density

We’ve built up without building better. Vertical density in micro-units without corresponding infrastructure for transport, schools, green space, or services. We’re building for being counted, not living. It’s density for density’s sake. And the only real metric going up is the price per square foot.

Parking, Not Commuting, Is the Real Crisis

This isn’t about 8 a.m. traffic anymore. It’s about what happens at 10 p.m. when you get home from work and there’s nowhere to park. Or about the delivery truck at 11 a.m. blocking the road because there’s no loading bay. Or the construction site that takes up four residential spots for six months. Multiply that by 365 days, and you get… Halifax.

It’s this last point that is the most noticeable point of difference.

Here’s a reasonable estimate for the number of vehicles on the Halifax Peninsula in a typical day:

Resident-owned vehicles: ~65,250

Vehicles coming onto the peninsula daily (for work, shopping, healthcare, tourism, etc.): ~90,000

Business and commercial vehicles (deliveries, trades, services): ~13,500

Taxis and ride-shares: ~2,375

Emergency vehicles (police, fire, ambulance, etc.): ~70

Revised total vehicles on the peninsula in a typical day: ~170,000

Roughly, that would be about 8,000 vehicles moving or parked per square kilometre. I should add that it’s mostly parked. Vehicles in Canada only move about 1 hour a day on average.

If you wonder where I get all these numbers, it’s from StatsCan, HRM Data sets, and a small number of commissioned studies like this one from Dalhousie: Halifax Traffic Activity Study.

None of this is comparable to anything in our history.

1940s–1970s: The Peninsula was filled with families—often large ones—in single homes, flats, or duplexes.

Typical household size: 4–6 people was common.

Children per home: Higher birth rates meant more kids, more bedrooms per house were filled.

Density by headcount: Higher, even if the housing stock was smaller.

Now: Fewer People per Unit

Today: The dominant household type is singles or couples, often in one-bedroom or studio condos/apartments.

Typical household size: ~1.8–2.2 people.

Children per home: Fewer; many new buildings are not family-oriented in design or price.

Density by dwelling: Physically denser (more units), but socially sparser (fewer people per unit).

The Result

While you might have more doors today, you likely have fewer school-aged children and fewer extended family homes. Neighbourhoods like the West End or North End may have housed three generations under one roof in the past. Now you have one couple and a golden retriever.

So:

More buildings ≠ more people.

Urban density ≠ demographic richness.

What’s being built and who lives there has shifted the cultural and social density of the place—even if the population number on paper seems stable.

And the Cars

This is no one’s fault. Nobody’s doing anything wrong. We all just want to live our lives to the limit of our economic capacity and need for ease and convenience—in lives that leave little time for leisure, travel, walking or, really, anything that requires margin. Time is simply not something any member of the modern household seems to have. It’s about economics, the structure of the household, and the weather. It’s about all of us being pushed to the limit.

So we drive. We drive everywhere. Few among us can organize a walking lifestyle or even wait for a bus. Only about 1/3 of our households own a bicycle and most of them go unused. We drive to the grocery store, to daycare, to the gym, to work, to school, to our second job, to pick up the takeout we didn’t have time to cook. And we park—badly, frantically, illegally, or in the street.

There are over 75,000 people on the Halifax Peninsula now. There are nearly as many cars. The city was never designed for this. It can’t be. The traffic you’re in isn’t “rush hour” anymore. It’s just people trying to move their cars around a 3 x 7 km parking lot.

The Peninsula isn’t underpopulated. It’s over-capacitated. And the clearest sign that we’ve passed the point of optimal growth—the peak of the curve where growth equals prosperity—is right there in front of you, idling next to the empty bike lane.

This isn’t a failure of planning. No one is planning anything. The HRM Planning Department, is heart-sinkingly misnamed. It’s a failure to admit we’ve stopped planning. It might better be called the Utopia of Rules after David Graeber’s sharp take on bureaucracy as both a form of control and a fantasy of fairness. We’re not suffering from bad planning. We’re suffering from the fantasy that planning is still happening. Because no one—not City Hall, not the Province, not even the federal agencies that pretend to know best—has made any effort to model, to ask, or to answer the most basic questions of all:

Where are we on the growth curve? Where are we going? What kind of city do we want to be? What are the practical and geopolitical limits of Halifax?

Because if we don't know where we are, it doesn't matter where we go. Every step might just be taking us further into decline, congestion, and quiet civic despair. This isn’t going to be solved by a survey or a knowledge cafe public consultation. It takes factual knowledge, leadership, and real responsibility. Halifax doesn’t need more growth. We need a treatment for a bad case of bureaucratic urbanism—the disease of filling cities with rules while draining them of meaning.

And maybe a place to park while we’re at the hospital getting that checked out.

Economic growth does produce prosperity, generally speaking. That comes from improving productivity, which has actually been declining in Canada since 2015. Population growth on its own does not produce prosperity. Otherwise Bangladesh would be much wealthier than Canada.

There’s a massive difference in growth of GDP per capita (Switzerland) and sheer uncontrolled population growth (Congo). This article seems unclear on these distinctions.

SO. Yes, too many high rises. Failure of bussing, local hop-on, hop-off, around the Peninsula. Failure of ride-share type solutions. BAD failure; no commuter rail from Sackville/Bedford/Enfield/Windsor. Why didn't government move more of its offices to Mainland, or Dartmouth?