Halifax. A Tale of Two Cities

Why a Dollar in Musquodoboit Harbour Builds the Future—While a Million on Spring Garden Road Just Destroys the Past.

The greatness of Halifax (HRM) lies not in its towers, but in its towns.

What Kind Of City Is This?

Halifax (HRM) may call itself one city, but it's two worlds: the bureaucratic capital on the peninsula, and all the quietly competent communities like Musquodoboit Harbour spread over almost 5,500 square kilometres of mostly woods and waters. Shout out to Hubbards, Bedford, Waverley, Enfield, Elmsdale, Sheet Harbour, Sackville, and all the other communities, old and new, who know exactly who they are and what they want to be. They pay pretty much the same taxes but live in vastly different realities—one dense downtown, drowning in studies and ideology, the other ribbon communities begging for clean drinking water and a local school.

What kind of city builds bike lanes before clean drinking water?

What kind of city talks about stadiums when people are sleeping in cars on rural backroads because there’s no housing at any price?

What kind of city spends endlessly on space-laser level parking enforcement and other gadgetry but doesn’t give communities any core funding for localized social programs?

What kind of city spends millions to welcome half-day cruise ship tourists who want to leave, but can’t find summer jobs for kids in rural communities who want to stay?

A Tale of Two Cities: Halifax and the Other Halifax

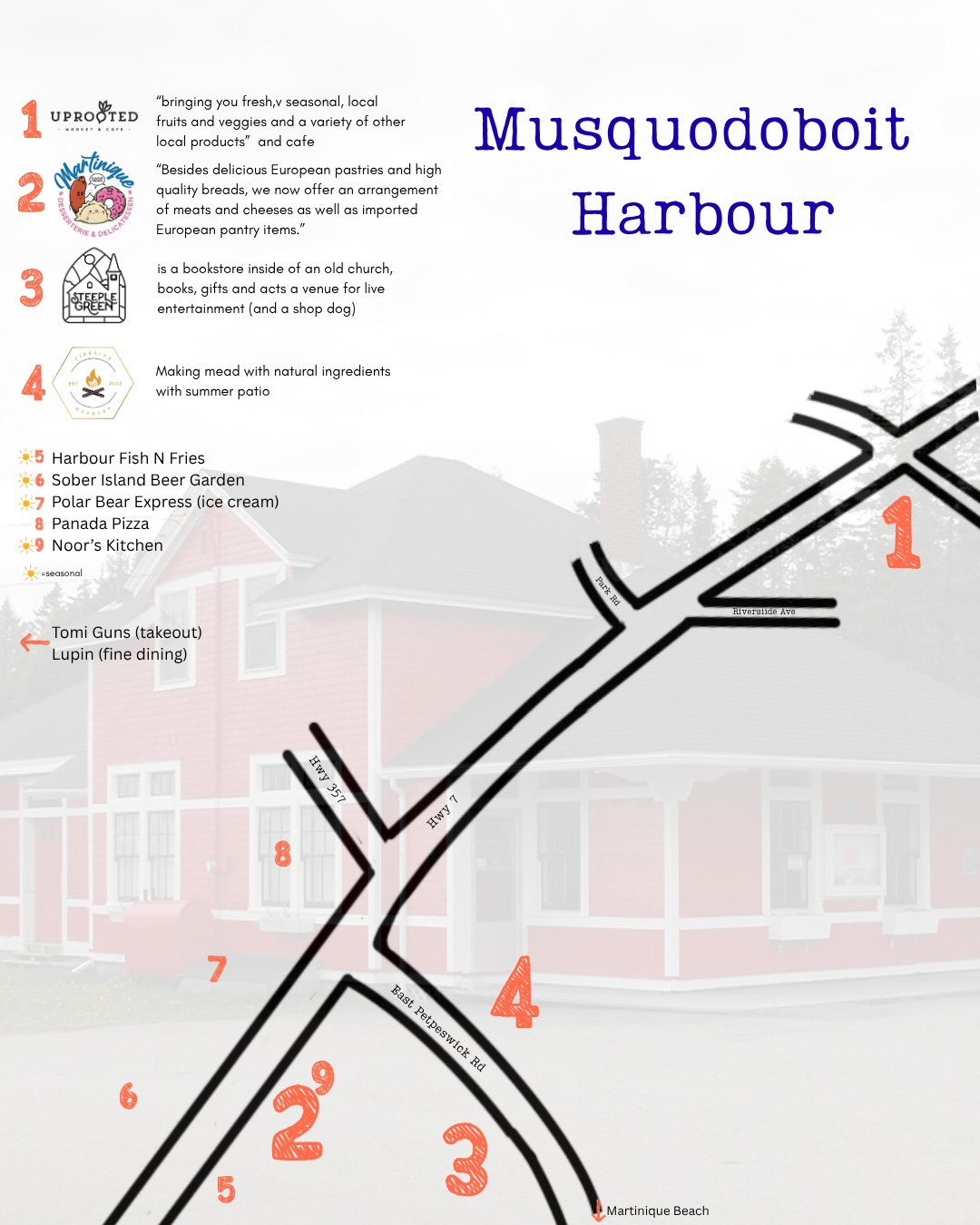

On the map, they are the same place. Halifax Peninsula and Musquodoboit Harbour. One city. One mayor. One budget. But in every other way—culturally, economically, politically—they could not be more different.

The peninsula is where the money is counted and spent. It's the seat of government, home to City Hall, Dalhousie, the CBC, the Legislature, the banks, and a fortress of bureaucracy so thick it often mistakes itself for the public it’s meant to serve. It’s a city of bureaucrats, consultants, committees, and strategies for the next strategy. Millions are spent on stadium studies and "active transportation" plans while traffic grinds and storefronts shutter along liminal concrete blocks. Over-restaurated and retailed to the point that no one can make any money, it is a machine that runs on paperwork and publishes its own applause.

Musquodoboit Harbour, on the other hand, has no everyday government - classic taxation without representation that seems painfully ironic in a place that was once a cradle of representative government. It has people. It has gumption. It has a thousand volunteer hours for every city dollar. It’s rich in spirit but so poor in fact that people come to mistake the Lion’s Club or local Soup Kitchen for government. Here, city government is something that mostly happens to you, not for you. Ussually dropped top down like a bomb out of the blue. The local councillor does his best, but over the years, the job has come to resemble that of a shop steward for the bureaucracy in a Kafkaesque workplace—explaining the unexplainable and apologizing for the unavoidable to a dozen small communities under their circuit of woe.

Everything government is a special case, a photo op, a gift, an occasion that the locals are expected to come out and celebrate to show their thanks to whatever elected official chose to take the ego boost.

And yet, Musquodoboit Harbour thrives in a different way. Without a mandate, responsible government, or a budget, people show up anyway. Community groups, fundraisers, bake sales, trail crews, Christmas parades, clean-ups, potlucks. It’s a government of sorts—always giving, organic, responsive, and deeply human. There is more true democracy in one Lions Club meeting than a dozen council reports.

But the infrastructure gap is staggering. While tens of millions flow into peninsula upgrades—bike lanes, street art, crosswalk beg buttons—Musquodoboit doesn’t even have clean public drinking water or a modern sewer system. If you want high-speed internet, better call Starlink. If you want a sidewalk, walk in the ditch - the community has considered it, and there are a dozen higher priorities.

Maybe worst of all hope pretty much uniquely outlawed on Nova Scotia’s Eastern Shore. A rule, inherited from the city at amalgamation says to develop or built anything a lot must have more than 10 metres of public road frontage. But just about the only public road frontage is the old #7 Road that winds along the shore. And a lot of that is waterside. It’s a classic Catch-22. The city says they won’t put in any infrastructure such as road grid, water, sewer or services until new development justifies it. But there can’t be any development because there is no infrastructure. So from Porter’s Lake to Ecum Secum it’s just one long Ribbon Development.

What’s Wrong With Ribbon Development?

Ribbon development—the linear sprawl of homes and businesses along highways or rural roads—is the urban planning equivalent of building a 100 story building when the fire department only has 5 story ladders. It’s costly, inefficient, and ultimately dangerous.

Here’s what’s specifically wrong with ribbon development:

1. Infrastructure Inefficiency:

Linear patterns dramatically increase costs. Instead of compact areas served by a central water system, sewer, power grid, and transit, utilities must stretch thinly over miles. It's like making a sandwich that's all crust and no filling—costly without satisfaction.

2. Traffic and Safety Hazards:

Ribbon developments typically front busy roads, meaning every driveway and storefront, gasbar, and Tim Horton’s entrance is another potential collision zone. Picture a highway turning into a seemingly endless driveway dotted with brake lights and close calls.

3. Community Isolation:

Long strips of development tend to lack cohesion, community spaces, and shared identity. People pass by rather than stopping, socializing, or investing personally. It's the urban-planning version of small talk—everybody’s there, nobody connects. And a few villages carry all the burden.

4. Loss of Agricultural Land:

Ribbon development consumes productive farmland at an alarming pace. The highway-side appeal of rural land converted to residential or commercial use often fragments larger plots into unusable parcels—like carving the Thanksgiving turkey into unrecognizable pieces.

5. Environmental Damage:

Linear sprawl fragments wildlife habitats, disrupts natural drainage patterns, increases runoff, and complicates stormwater management. It's not just paving paradise—it's paving it in a way that makes everything downstream soggy and unhappy, especially when the ribbon runs along by the sea.

6. Poor Public and School Transportation:

Efficient public transit is notoriously difficult in ribbon developments. Stops must be frequent to serve thinly spread homes, yet they remain too sparse to justify frequent service. It's transit designed neither for riders nor drivers, pleasing precisely no one. And the children spending hours a day of their rural childhood on buses when they could be exploring and learning about their local woods and waters.

7. Unpleasant Aesthetics and Identity Loss:

Long strips of businesses and homes often appear monotonous or unattractive. Without a concentrated core or defined neighborhood, these places become a bland blur. Everyone knows a nice place when they see it. But with ribbon development you never quite get there—it works, but nobody dreams about it.

8. Economic Sustainability:

Property values stagnate as maintenance costs rise over time. Local governments find themselves saddled with upkeep and servicing liabilities far beyond what tax revenue can support. It’s a municipal Ponzi scheme, paying tomorrow’s bills with today’s short-sighted deferral of repairs, maintenance, and improvment.

In short, ribbon development isn’t just inefficient—it’s unsustainable, anti-social, expensive, ugly, dangerous, and bad for both the environment and local economics.

A Community of Communities Going Nowhere

There are a hundred Musquodoboit Harbours across HRM—small, spirited communities paying into a system that barely knows they exist. They are not against the city. They are the city, or whatever it might be more rightly called, given that it is over 70% woods and waters, which is left unmanaged and unaccounted for in the urban and up ideology. But without representation in numbers or structure, they are locked into a system that rewards density, not decency.

This is not an urban-rural fight. This is a call for balance. For recognition. For the idea that the greatness of Halifax (HRM) lies not in its towers, but in its towns.

Because here’s the truth: Halifax doesn't just have a housing crisis. It has a governance crisis. A vision crisis. A crisis of forgetting who it’s really for.

The solution isn’t another master plan. It’s a modest, radical idea: share. Share the taxes. Share the say. Share the future.

Meanwhile In Halifax

Growth for Growth’s Sake Is the Logic of Cancer

Here’s where it starts.

Everyone in government talks about growth. It rolls off the tongue like a religion. Growth in housing. Growth in population. Growth in GDP. Growth is good, they say—because it’s always been good, right?

But growth for growth’s sake is not a strategy. It’s not even rational. It’s the logic of cancer—cells multiplying without purpose, eventually consuming the very body that sustains them.

So we must ask: what’s the right size for us?

This ain’t Toronto. This isn’t Montreal or Vancouver. Halifax is a city built on a 3x7 kilometre peninsula—essentially an island with bridges. Limited land. Limited access. Limited capacity. At some point, the returns on further growth begin to diminish. At some point, the costs of infrastructure, congestion, debt, social breakdown, and ecological stress start to outpace the benefits. At some point, every new condo is less a generator of prosperity than a monument to speculative overreach.

Even Manhattan had limits. Halifax isn't an exception; it's a cautionary tale in the making.

So the real question is: when does the next development scheme destroy more wealth than it creates?

How would we know?

What do we measure? Do we track mental health? Commute times? Vacancy rates in commercial buildings? Sewer overflows into the harbour? How many people leave the province in despair each year because they can’t afford to live in the city they grew up in?

Do we measure livability, or just permit approvals?

Who do we believe? The people paid to promote?

Do we measure civic well-being, or just construction cranes?

And who is brave enough to say “enough”? Who is willing to take responsibility for calling the peak? Because leadership isn’t always about more. sometimes its about saying when we’ve had enough.

The truth is, we’ve never even had that conversation.

Because to question growth is to challenge an unspoken religion of urban planners, developers, and bureaucrats who’ve built their careers on perpetual expansion. But Halifax doesn’t need eternal growth. It needs meaningful prosperity. It needs beauty. It needs enough.

Enough to live well. Enough to build with care. Enough to leave room for the next generation to dream.

Until we can define what "enough" looks like, we’ll keep pushing past it. And eventually, we'll wake up to find we’ve grown ourselves into a city no one can afford, no one can navigate, and no one really loves.

So again: What’s the right size for us? 500 people per square Km? 5,000? 50,000? Few could even name an order of magnitude because it is simply never talked about.

If we don’t ask now, we’ll be forced to answer later—when the damage is already done.

The Economics of Community Investment

In business and economics, there’s a basic idea that’s easy to understand and hard to ignore: putting money into something early—when it’s just starting out—creates more return and more wealth than pouring money into something that’s already mature.

Think of it like planting a tree. The first few dollars buy the seedling, then the work to water, and fertilize. With sunlight and time, the tree grows and gives shade, fruit, maybe even lumber. That small early investment leads to decades of value. But if you wait until the tree is already tall and old, throwing money at it—pruning it, painting it, adding lights—doesn’t give you much more. It might even cost more to maintain than it’s worth.

Economists call this diminishing returns. It means that every extra dollar you spend in a mature system gives you less back. That’s what’s happening in places like central Halifax: lots of money going in, not much new value coming out. Meanwhile, early-stage communities like Musquodoboit Harbour are like that young tree—full of potential, just needing a little water and sunlight.

From a business perspective, that’s the smart place to invest.

Here’s a visual of the S-curve showing how early investments yield the highest returns. The early stage (green) is where a place like Musquodoboit Harbour sits—small investments here spark big growth. The growth stage (blue) is the sweet spot. The mature stage (red) is where most of the Halifax Peninsula now sits—high costs, low returns.

We see this everywhere. You can invest $100 million into downtown Halifax today and barely move the needle. The grid is there. The roads are already paved. The sewers are already in. The bureaucracy is already entrenched. You’re paying top dollar to fix things that used to work.

Now compare that to a place like Musquodoboit Harbour. It’s early on the curve. It doesn’t yet have proper drinking water or sewer system. It has willing people, open land, and ambition. A fraction of that $100 million could change everything. Build the basics. Attract jobs. Multiply opportunity. Make it beautiful. That’s where real wealth is made.

When you invest early—in infrastructure, services, and people—you’re not just spending. You’re seeding prosperity. You’re building the kind of place that pays you back over generations.

Does that mean every small community should grow into a big community? No. Absolutely not. It might not grow at all in the Halifax sense. It should become the best it can be. The place the local people dream of. It should realize its unique vision. Many who are old enough will remember pre- amalgamation Dartmouth, Bedford, Sackville, and Waverley. These are examples of different communities that had clear visions and local passion. Each offered a unique view of life in Nova Scotia.

What Does Halifax Have To Offer Nova Scotia?

Ultimately, to find our purpose, to experience the progress and prosper we’re always talking about in Halifax, I think we need to answer one question. What does Halifax offer Nova Scotia? What can Halifax contribute to build a prosperous and peaceful Nova Scotia? If that was our decision rule. If that’s how we thought about things. I’m positive the future would be a lot better.

What Does Halifax Have to Offer Nova Scotia?

Halifax behaves like a petulant child—spoiled by attention, indulged by government, and convinced of its own importance without having to prove it. While the rest of Nova Scotia strains to build an economy, Halifax builds a brand. While the province and Ottawa try to spark real economic engines—farms, industry, and sustainable fisheries—Halifax is busy pouring $21 cocktails. It's the first little pig of the fable, not building with straw but with ideology, bureaucracy and slogans.

The City Hall’s priorities are increasingly unmoored from the province and the rural communities that surround it. Its political class obsesses over boutique policy and social engineering. It commissions studies, hires consultants, and holds public consultations with the same feverish energy others use to plant crops or haul nets. Whatever the issue, the problem, or the opportunity, the answer is always the same — Consultation. All while the infrastructure crumbles, the cost of living climbs, and business confidence evaporates.

So let’s ask the question no one inside the bubble dares to ask:

What does Halifax actually offer Nova Scotia?

Not in terms of self-image, not as a cultural capital, not in glossy campaigns or slogans. But in the hard currency of contribution—economic, social, civic.

Because if Halifax is to be the capital in more than name, it must lead not just in size but in service. It must offer more than ambience—it must offer value.

What if every policy decision in Halifax had to pass a simple test:

Does this make Nova Scotia stronger?

Does this build something real?

Does this serve people outside the peninsula as much as those on it?

If that was our decision rule—if we judged success not by how loud Halifax shouts but by how well it serves—our future would be not just better. It would be ours.

Until then, Nova Scotia will keep waiting for its capital to grow up. And Halifax will keep wasting captial.

Who is Going To Figure Out The Future of Halifax?

Halifax is one city in name only. One half is drowning in plans; the other half just wants a working well.

What we need to hoist in is that the cavalry isn’t coming from inside the existing amalgamated bureaucracy. Our councilor, the nice woman on the 311 line, the Mayor riding the float and cutting the ribbons. We can’t expect the folks who’ve turned City Hall into a Kafkaesque temple of red tape to suddenly pivot and rescue us from the consequences of their own inertia. You can’t fix a city with the same mindset that broke it.

If real solutions come, they’ll come from the margins and they’ll come from change.

The situation is not likely to change when there are so many people in on the con.

Musquodoboit Harbour isn’t just a rural suburb—it’s a living model of civic resilience. It’s messy. It’s scrappy. It’s human. And it might just hold the answers that downtown Halifax has lost in a sea of strategic frameworks.

So if you're looking for someone to figure things out at City Hall?

As Matt Gurney points out on THE LINE, lots of smart, competent people have government jobs. There are shining lights of unusual competency in every department, and at every order of government, And we’ll will never get tired of saying good things about the men and women of the Canadian Armed Forces, the first responders, and the people at the frontline of health care and social services — true miracle workers we support as they support us.

But there aren’t hidden capabilities. There aren’t secret teams. There’s no one who is truly responsible for the foundational change we need. All those jobs have one thing in common. They’re supposed to hold things together — just as they are — not reimagine any different city or a different way of doing things.

Don’t look at the 250 nice, competent, confident, and comfortable in the city planning department. And don’t look to the 5,000 plus people working for HRM.

Look for someone who sees the problem, has a creative solution, and says, “I will be personally responsible for this.”

In Defense of Small Communities and Their Stories

I’m feeling unwell about the CBC’s recent foray into Musquodoboit Harbour’s village pump politics. With a headline-grabbing piece on—you guessed it—a literal village pump, it’s almost endearingly on-brand for the public broadcaster. After all, they’ve been doing this sort of thing since they woke up: parachuting into small towns, squinting to find some …

Like you, I have a unique view of the Halifax Regional Municipality.

I grew up in the village of Waverley for my first 20-plus years.

I’ve lived around the Jubilee Road on the peninsula in Halifax for almost 40 years.

And for the last 25 years, my heart has been wandering along the river, the lakes, and the foreshore of Musquodoboit Harbour.

As the 30th anniversary of the amalgamation of the Halifax Regional Municipality comes up, about half my life has been amalgamated, and half not amalgamated.

I’ve thought I would move away twice.

Once when I was 16. I ran away from home, well, ran away from school really where the alternative seemed to be not to be alive at all, and slept in just about every Salvation Army, roadside ditch, and dirty couch from Sussex New Brunswick to Gibson’s Landing. Which all ended in love and other sordid disasters that I won’t go into right here except to tell this cautionary tale as it was told to me, “drink black rum if you gotta, but let the cocaine be”. A flat top guitar and that advice is the only reason I’m here with you today. I was back home by 18 with a brand new plan. Live and Learn. No matter how much effort was required.

The second time I thought of moving away was 40 years later, at the other side of life’s adventure. With more than a few successful TV series on the go, money in the bank, and a reputation that was getting me invited into the industry’s idea rooms, I thought we should move to California. Amanda had the sense to say, let’s just try it from a season. In the fall we got a beautiful beach house on Balboa Island, in Newport Beach, a reasonable drive from Santa Monica, Culver City, and all the meetings that pass for work in L.A. California had everything. No matter what you are into. No matter how obscure. You’ll find a thousand other people with exactly the same passion somewhere along the Pacific Coast Highway 1. Vintage guitars and amps? VW Buses? British Motorcycles? Wildlife Rehab? Diving? Sailing? Writing? Freemason’s Lodges? Bow Tie design? Everything I’d ever dreamed of was there. So it’s still hard for me to explain to you why by April I was stone steady sure it was time to go home to Nova Scotia. I would say it had something to do with the scale of things. California, like BC is sort of Jurasic. Nova Scotia’s northern joy just feels more human scaled.

So here I am both by birth and by choice.

All to say, I’m well-positioned to write a Tale of Two Cities.

I think most people who truly love this place have a similar story. You’ve seen life’s other side. And you chose Nova Scotia. So I’m sharing this with you.

I love this John Wesley! I too left Nova Scotia twice and came back, once for 18 Months to Vancouver Island, because I was seeking a better life, which unfortunately due to relationship problems, forced me back home. My second time it was because I met someone that I was pretty sure was the right person this time, who was transferred to Ottawa. I reluctantly moved there with him, scared to death that it wouldn't work and I'd have to come home crying again. Well, that didn't happen, it turned out that my heart was with the right person this time and we prospered in Ottawa. I missed home of course, we couldn't get into a social circle no matter how hard we tried, I gave up! I quit my comfy City job with all the benefits to provide for me in my retirement. We sold our first house we bought together, moved back to Halifax after 10 years of what felt like a failed adventure, but I guess it really wasn't. We struggled a lot, trying to re-establish our selves here, although we were back with all our friends and in my case my family. Nineteen years after returning home and twenty nine years into our relationship, we are happy and love being here, despite the direction the City has taken.

There is definitely a flawed logic in much of what HRM does. Perhaps a small town advantage is scale? People feel connected to a place, each other and know what's going on. For example: Would Musquidobit residents agree to HRM councillors secretly planning to spend $200m to buy & demolish 12-14 historic buildings (with 50-70 rental homes)& cut 80 trees on their Main Street to add a 2nd bus lane even though it won't reduce congestion or traffic? Halifax is far away so they likely don't know that's what's planned for the last historic neighbourhood on Robie St. And in the dense disconnected urban core most people have no idea that's what HRM is up to. But Musquidobiters and all small HRM town ought to know and be interested to where their scarce tax dollars are headed. They should demand that the $200m go to rural micro-transit, more buses, more drivers, carshare, bike-share and building or protecting affordable housing. Help make that happen by writing clerks@halifax.ca