Forget The Oak Island Mystery. This Oak Tree Is A Real Mystery.

Before There Was Halifax, There Was This Tree. Halifax's heart of oak may be the oldest living thing in the city. But there's a problem.

In a busy park in the heart of Halifax stands a tree probably older than the city itself. A living monument. A white oak that survived empires, fires, axes, and explosions. This is its mystery—and ours.

Maybe this is a break from the politics of bike lanes, economics of Nova Scotia, and the effort of argument we’re all struggling to learn. Or maybe this is a story that gets right to the heart of the whole thing. You can decide over these next couple summer reading posts.

Whatever the takeaway, my hope is that this story takes you back happily to some of the trees in your life. They say the present is the fruit of the past and the seed of the future. For me, that’s a story symbolized by trees.

I have been bound to a series of trees that I have loved with all my heart since I was seven years old. A succession I can recall as clearly as any memory. The first was actually a pair of scraggy spruce that formed just enough of an arch canopy to build a little fort and place of solitude inside. The next was a balsam fir — the first great climbing tree of my life. I can still smell and feel the sticky resin that blackend with dirt on my hands and face and stuck for days. A long succession of tree love affairs over a lifetime.

There was a Mountain Ash that supplied the thousands of little orange berry bullets for imagined battles among us boys. There was a big white birch at Black Point that gifted us enough bark for our first little canoes. There was a white ash that we carefully split for our first bows and arrows. And there were old pines of all sort. Big lush and green with their thick soft orange carpets of needles underneath. The only place I really feel at peace.

But I wasn’t born a naturalist. My brother and I, with our first hatchets, were a pestilence on the trees of Nova Scotia from Halifax to Pictou County. Our main victims were the soft, easy prey of young poplars. Easy enough to chop but tall enough to make dramatic falls. My lifetime of love grew from those early violent days that I’ve observed many men never grow out of. There’s something about felling trees that sits deep in the restless, pent-up, destructive/creative minds of men.

I spent my early childhood playing in the woods at the end of the old logging roads that led into the great Waverley Game Sanctuary. A half-dozen of us boys gathered there daily to explore our small patch of wilderness. Our mothers tossed us out of our homes and told us not to come back until mealtime. To keep us busy, they equipped us with sharp axes, bow saws, and boxes of wooden matches. Our woods were far from primeval. It was a cut-over, scrawny mix of maples, elms, pole spruce growing like porcupine quills on the landscape, and an occasional oak demanding its space but yielding to our treehouse dreams and big branches for the most adventurous tree climbing.

The proverb "Mighty oaks from little acorns grow" is attributed to Geoffrey Chaucer. He included it in his work, Troilus and Criseyde, around the year 1374. The phrase highlights the idea that great things can develop from small beginnings.

I like the variation of this theme, often attributed to Henry David Thoreau,

“Every oak tree started out as a couple of nuts who stood their ground.”

It’s a profound message about resilience, perseverance, and the potential for greatness inherent in seemingly ordinary beginnings. Monumental achievements often emerge from humble origins and seemingly insignificant beginnings.

Growing oak trees happens at a cadence different from our human lives. They grow over hundreds of years. So all through history humans have sensed the oak tree held special knowledge and ancient wisdom.

The oldest living thing in your neighbourhood is almost certainly a tree—and that tree is probably a white oak.

It reminds us that time and growth aren’t measured in what we build, but often in what we leave alone.

You’ve passed it a hundred times. Maybe it shades a corner of the schoolyard, or leans over a crumbling stone wall behind the corner store. Some things are so big it’s hard to see them. Maybe it stands alone in a field.

You might not know it’s a white oak. You might not think about it at all. But it marks the decades and centuries as you mark the years. There might be bigger trees, bigger canopies, or height, but none older or stronger than the white oak.

It’s about time. There are oaks still around that were old trees when this beech was planted. Animals, and people eventually, coming and going. Children running and climbing. Horses. The strange parade of everything that came after the forest and before the condos.

Our local White Oak Tree is in an open field near The Jubilee House.

We’re over in our local field morning, noon, and night. It’s funny to think a field is so useful, but it is for us. Walking, dog runs, meeting with neighbours, kids’ play, and activity of all sort from tobogans to art projects. A certain amount of picnicking and sunset romance goes on. From birthdays to whatever you call it when people play at sports, like just playing catch, there’s always something happening. Whatever the season or weather, it’s a busy place. And at night… teenagers doing teenager stuff.

I’ve always known this place as The Horsefields. Somewhere in the recent past, the Municipality put up a sign that calls it Conrose Park, but there’s no explanation of what that means to anyone or why they chose to rename it something different than what it was. It was called the Horsefields from a time when over 6,000 horses lived on the Halifax Peninsula, and they all needed grazing and pasture space.

You can see the Horsefield Oak Tree near the centre of this satellite view.

I’ve always noted the tree because it reminded me of a tree that loomed large in my youth — the big Oak that stood at the end of the fields in what is now Oakfield Park. From childhood to well into my 30’s it was a destination and the climax of the nicest field walk I knew. From Cub Camp Jamboree adventures to a long post-wedding walk, and on to going with growing kids and dogs, walking to the Oak Tree in the field was our walk. Our getaway wasn’t more than a half of a mile from one end of the fields to the other. But it often took most of a morning to follow a beaten path, through rolling fields, over old stone walls, and across tiny brooks, poking the ground with sticks, until we reached the great oak — more historic monument destination than mere tree.

There’s also a love of tree climbing in our family.

There’s a lot going on in the Horsefield oak’s story.

Today it has a few ‘children’ at the edge of the field:

Here’s the youngest white oak we’ve seen and an older sibling surviving and growing around the CN rail fence at the edge of the field. White oaks can take a lot of damage and survive.

And there’s bad news from the Red Oak cousins. They seem to be attractive to the darn Japanese Beetles that are wreaking havoc on Nova Scotia’s roses and grapes.

The Beginning of an Oak Tree Mystery

In the last few weeks, Dorothy and I have been measuring and doing research on the big Horsefield Oak.

We identified the tree as a white oak based on several clear indicators we researched. It was a fun summer project for her and me. Most notably, the leaves have deep, rounded lobes with no bristle tips, which distinguishes them from red oak species that have sharply pointed, toothed lobes. The bark is pale gray and flaky, breaking into irregular plates—typical of mature white oaks and unlike the dark, ridged bark of red oaks or the thick, corky bark of bur oaks. The tree’s massive, open-grown form—with a broad crown and wide-spreading limbs—also fits the classic profile of a white oak allowed to grow without competition. Together, these traits—leaf shape, bark texture, and growth habit—helped us conclude that this is a white oak (Quercus alba) — the King of Trees, the biggest, longest living, hardest, and most impressive of the oaks.

The first thing we considered was if this would be counted as one tree for purposes of age, history, and biological identity—despite the triple stem. It appears to have grown from a single seedling with a unified root system that later split into multiple stems—a natural response to storm damage, early pruning, or genetic growth habit. At breast height, it’s still one tree. You can think of it as one veteran white oak with a trifurcated crown.

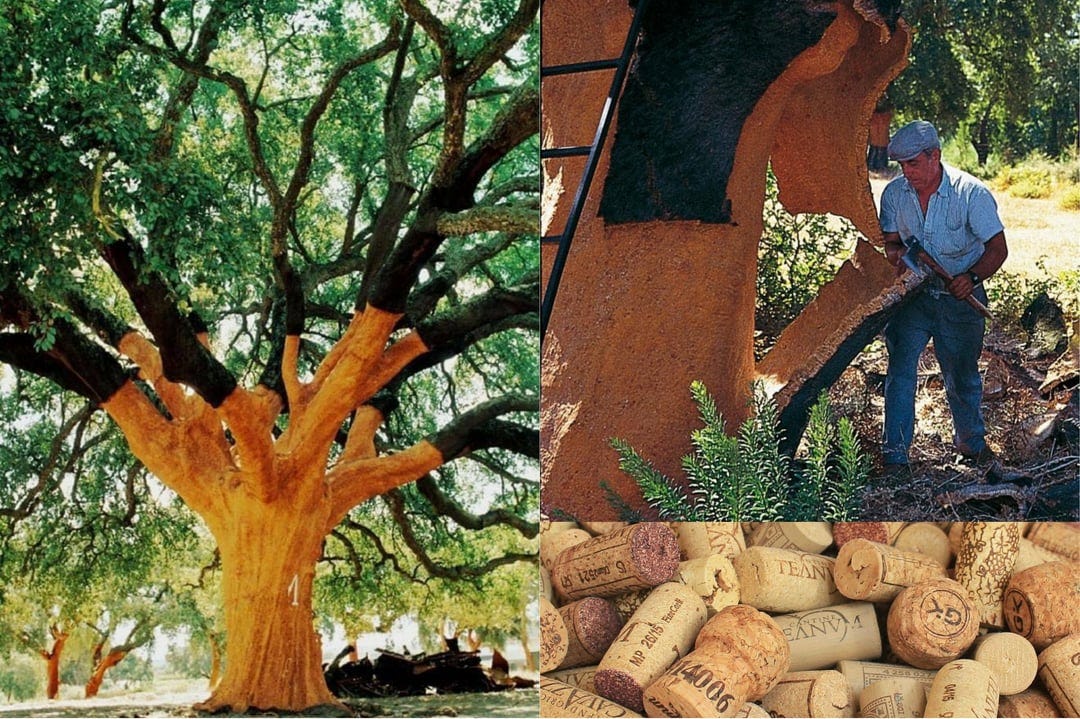

When you see the bark of a big oak, it’s not difficult to see its close relation to the Cork Oak. The original stoppers in wine bottles are called corks because they were made of the bark of the cork oak tree (Quercus suber L.) which grows naturally in Portugal, Spain, and Italy.

SIDEBAR: If you like big and old trees, you might like the Big Tree Seekers group on Facebook.

Estimating Age With The Growth Factor Method

The Growth Factor Method is the most widely accepted forestry method for estimating tree age when core sampling is not done. You can use this to get an estimate of the age of any tree you can identify.

Formula:

Age=Diameter in inches×Growth Factor

White oak growth factor: 5.0 (standard estimate for slow-growing oak in eastern North America)

Age=72"×5.0=360 years

If you don’t know the diameter, like Dorothy and I, you can hug the tree and measure the hug lengths to get the circumference and estimate the diameter with the formula:

In our case, the circumference was almost four Dorothy hugs around.

It’s a rare thing. Most white oaks in Nova Scotia are much smaller, scrubby, or crowded by faster-growing species like maples.

Trees with trunks over 4 feet in diameter (1.2 m) are exceptionally rare. Ours, at 6 feet in diameter, is almost certainly among the largest living white oaks in the province.

White oak is a slow- to moderate-growing species. Looked at another way, general North American growth rates for white oak are:

In Halifax, on the fringe of the oak’s range, even well-sited white oaks would likely average around 0.15 to 0.25 inches/year over their life due to:

Cold winters and fog

Salt exposure (in some areas)

Limited summer heat for rapid wood production

Wind and storms

A white oak in Halifax growing in near-ideal conditions would likely average 0.2 inches of diameter growth per year—significantly slower than in the species’ southern range. This makes any tree over 5–6 feet in diameter very likely 260–360+ years old.

We were excited to estimate the white oak in our local field between 320 and 400 years old.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow never visited Nova Scotia, but the opening verse of his famous 1893 poem, Evangeline, which spoke of an even earlier time over 100 years before, was likely informed by conversations with storykeepers, travelers, and seafarers who knew Nova Scotia well. It’s maybe the best-known record of what Nova Scotia’s forests were like in their natural state.

And here’s where our troubles and the mystery really begin.

You’ll note that Longfellow paints a vivid picture of a particular forest and even name-checks a few tree species. But he doesn’t mention Oak, white or otherwise.

So we look up Oak in Nova Scotia, and any number of sites like the Halifax Tree Project confidently state that oaks are sparse in Nova Scotia and the only native oak species in Nova Scotia is Red Oak, the kind with pointy, even sharp ends on its leaves.

This is where we first got stuck.

The internet says White Oak is not native to Nova Scotia. It’s not just Longfellow’s poetry. Nobody’s talking about white oak in Nova Scotia.

Halifax is only 276 years old. Our tree seems likely to have been over 50 years old when Halifax was founded. So the likelihood it’s a purpose-planted tree is almost zero.

What’s the story of this lone giant standing in the field?

White oak isn’t supposed to grow here. Not in Halifax. Not naturally. Not natively. Not at this size, not at this age. Not without a reason.

And yet—there it stands, hidden in plain sight. We can see it on the satellite map. Six feet thick, canopy bigger than a mansion, older than the city, and older than the country.

How did it get here? Who planted it—or did anyone? Why was it never cut down? And what might it have witnessed, alone in that pasture, as animals, people, and progress rolled past like weather?

Coming Up…

Next time in The Bee, we’ll meet some of Halifax history’s most creative characters. We’ll stand up to the British Naval Empire, and we’ll explore enlightenment science, and Nova Scotia with all its faults and foibles, as we follow the trail of old maps, forgotten journals, ghost estates, and botanical blind spots, trying to answer another Nova Scotian oak mystery:

Where did this tree come from—and what does it mean that it’s still here?

In an age obsessed with unnatural speed, growth, and novelty, we might do well to spend more time with the oak. It doesn’t race. It doesn’t explain. It simply endures. Growing slowly in time with its seasons.

Halifax’s great Horsefield Oak has grown strong by growing slowly. A rough, quiet monument to the past we built on, and a reminder that a future worth building must be rooted in something older and stronger than ourselves. We’ve placed a maple on our flag, but it’s the oak that shaped history—battle-worn, scarred, vast, and stubborn—that still holds the weight of this place in its limbs. The oak can teach us the way to grow. We don’t need to name it to honour it. But we might need to stand under it now and then, to talk and listen.

While we work on our field oak mystery, I also get around to my Oak Island story, our experience filming there for CBC, and the early pilot footage we shot for the now-infamous TV series. And I’ll share the connection between me, Freemasonry, and the story that started the Oak Island mystery.

If you have any inside information about white oak, the Horsefields Oak, or factual corrections, please let me know and we’ll weave it into the next chapter of this great oak mystery.

Part Two: The Oak Tree Mystery. The Oak Island Mystery. And The Real Mystery.

Do you want a brief explanation of an acorn?

Loved this awesome narrative! Thank you! It was a most enjoyable read.

This is very fascinating to read about, I have done some light research on the history of trees in Nova Scotia, and I have found some other inconsistencies with the modern understanding of native trees and historical records.

One example is in the 1917 Native Trees of Canada (Morton and Lewis) they have Bur Oaks as a native species to southern Nova Scotia, but as you have said, red oak is the only recorded species as being native to Nova Scotian forests. I have always wondered if the loss of Bur oak as a native species was either caused by over harvesting causing them to be lost, changes in nomenclature making it so the species was recorded incorrectly, or some other clerical issue. (Open source [I think] link to the referenced book: https://archive.org/details/nativetreesofcan00mort/page/86/mode/2up)