Democracy Should Be Loud

It's getting too quiet down at city hall. Whoever the new Mayor of Halifax turns out do be, I hope they turn up the volume.

Here’s my case:

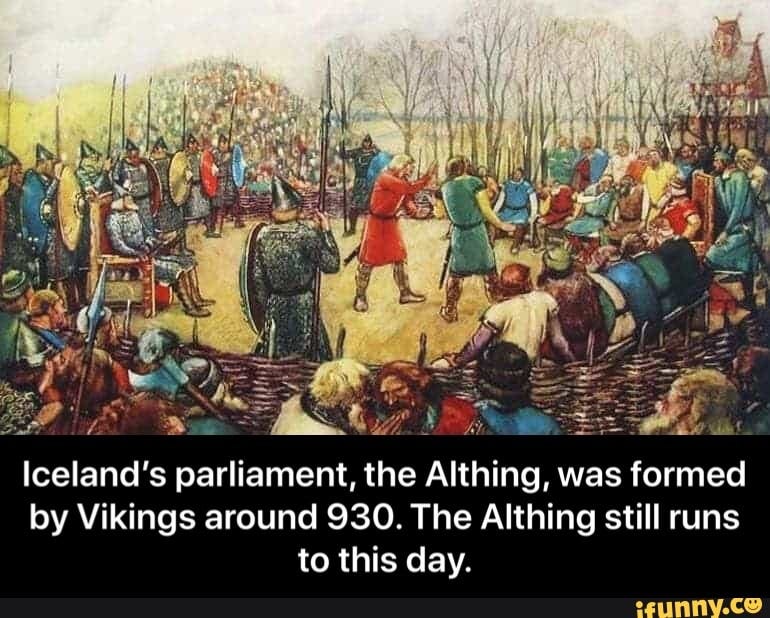

The current fear-driven, amalgamated, one-size-fits-all bigbox government, bloated with a too-big workforce of out-of-touch petty potentates and bureaucratic fiefdoms, is the antithesis of democracy. This sprawling system of endless rules is as far removed from the vibrant Halifax town meetings of the past, and the people caught up in the amalgamated communities, as we are from the Icelandic Thing. The real reason people don't bother voting in municipal elections is simple: it makes no difference. Their voices are drowned out by this machinery of power. Until we restore the form and forum of true democracy, participation’s heart rate will remain at a sickening low.

Take a look at this…

Democracy is an argument we have with ourselves about the shape of things to come. It is never settled.

The citizen's job is to be rude - to pierce the comfort of professional intercourse by boorish expressions of doubt.

John Ralston Saul

John Ralston Saul, is a Canadian philosopher and writer. This quote appears in his book The Doubter's Companion: A Dictionary of Aggressive Common Sense (1994), where he challenges the norms of authority and encourages ordinary citizens to be vocal and skeptical of those in power. Saul’s works often focus on the need for active, critical citizenship in democratic societies, advocating for discomfort and confrontation as essential tools for holding power to account.

The Icelandic Althing: The World’s First Loud Parliament

In 930 AD, on a vast plain in Iceland near the current capital, the world’s first modern parliamentary body was born: the Althing. Unlike today’s parliaments, this wasn’t a quiet, orderly assembly. It was called a “Thing”.

We still say, “We’re having a thing.” but the meaning has softened. A thing was a governing assembly in early Germanic society, made up of the people of the community presided over by a lawspeaker. Things took place at regular intervals, usually at prominent places that were accessible by travel. They provided legislative functions, as well as being social events and opportunities for trade. In modern usage, the meaning of this word in English and other languages has shifted to mean not just an assemblage of some sort but simply an object or event of any sort.

Hundreds of Icelanders would gather every summer at Thingvellir to argue cases, settle disputes, and make laws—often in loud, heated debates. There were no buildings, no formal seating arrangements; the debates happened outdoors, with chieftains shouting their positions while spectators cheered or jeered from the sidelines. The Althing wasn’t just a legislative body, it was a festival of loud, participatory democracy where Icelanders —rich and poor—could openly challenge their leaders. The messiness was the strength of the Althing, allowing a small, isolated country to govern itself for centuries without a central ruler. It proved that even in chaos, democracy can thrive.

Bring Back the Argument: Halifax Needs Its Democratic Voice to Rock Again

Democracy is supposed to be loud. It’s not polite, orderly, or for the faint of heart. It’s a constant, evolving argument about the shape of things to come. The problem with Halifax these days? It's gotten too quiet. We need to bring back the noise, the public debates, and the passionate disagreements that shaped our city in the past. It was messy, sure—but it was alive.

In the heyday of Halifax’s Town Meetings, the action helped develop the voices of individuals like Joseph Howe, an active and interesting local media, and collective voices of the people from the Co-op Movement to the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). They were arenas for debates that mattered. Joseph Howe’s outspokenness helped bring representative government to Canada. There would be no Redemption Song without the UNIA. Long meetings that stretched into the evening hours meant the public could attend, participate, and witness democracy in action. It was passionate, and yes, sometimes chaotic, but it was authentic.

Loud democracy held government accountable. In 1835, Joseph Howe, who was a journalist at the time, was charged with libel for publishing a letter in his newspaper, The Novascotian, that criticized local politicians and questioned government corruption in Halifax. Defending himself in court, Howe argued passionately that the press had a duty to hold the government accountable. Despite the odds, he won the case, marking a landmark victory for press freedom in Canada. This event solidified Howe’s legacy as a loud champion of free speech and laid the foundation for modern journalism in the country.

Now Look at Us

Then Mike Savage arrived. He promised a quieter council, and he delivered. Meetings shifted to the daytime, public attendance dwindled, and debates became... streamlined. Efficiency replaced passion, and that poses the question: How is that better?

Now it’s the 1830’s all over again. Mike Savage moves down to the Governor’s Mansion and his political acolyte becomes mayor. The new council will be hard-pressed with such little popular support or encouragement to stand up to the New Aristocracy… the 1,200 or so permanent upper bureaucracy at City Hall.

In the past, the aristocracy or “king’s court” were those who had stable positions, often backed by the wealth and security provided by the state. They didn’t have to worry about the ups and downs of market forces because their lives were protected, their incomes assured. In today’s context, government employees could indeed be seen in a similar light, with benefits that make their work lives secure in ways others can only dream of.

Loud Democracy Still Survives

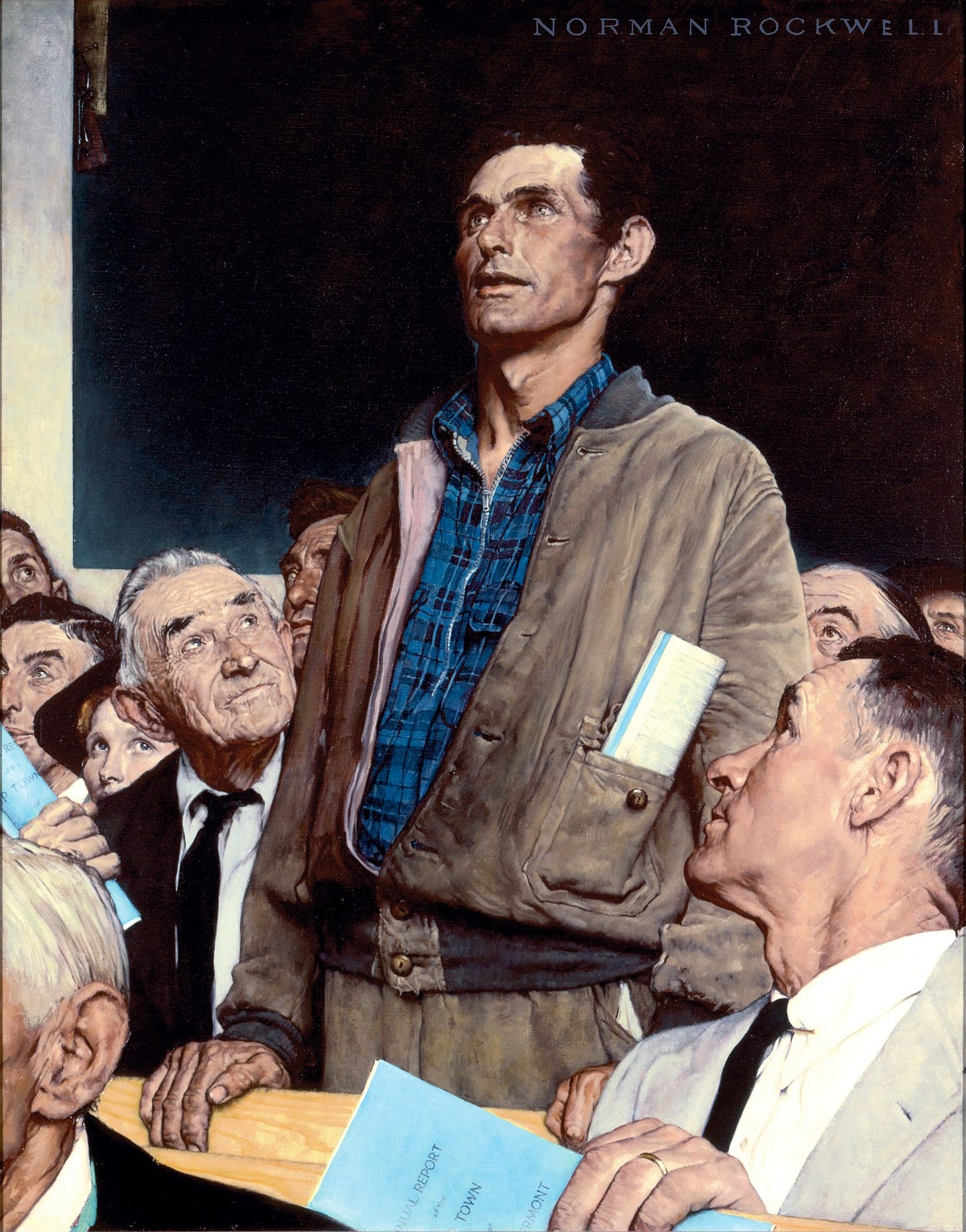

In the heart of New England, Vermont holds a tradition that vividly captures the essence of direct democracy—the Vermont Town Meeting. This annual event, deeply rooted in the state's history, serves not just as a local government meeting but as a vibrant testament to the community spirit and democratic participation that define Vermont. Norman Rockwell's iconic painting of a Vermont town meeting, "Freedom of Speech," immortalizes this democratic process, showcasing a lone individual standing among his neighbors, voicing his opinion with confidence and respect.

The History of Town Meetings

Town meeting traditions date back to before Canada or the US, originating in the 18th century. Importantly, it was a time when communities were smaller, and the town meeting served as the most practical form of government. This system allowed for all eligible community members to participate directly in the decision-making process, a stark contrast to the representative democracy seen in places that have artificially created big-box, one-size-fits-all permanent governments.

Over the years, Vermont town meetings have evolved, but their core principles remain unchanged. They stand as a forum where citizens can directly influence their local government, deciding on everything from public spending to local laws. This form of direct democracy reinforces the accountability of elected officials and fosters a strong sense of community among participants.

Vermont Town Meetings Today

Despite the passage of time and the progress of modern technologies that have transformed how we communicate and govern, the majority of Vermont's towns continue to hold their annual meetings. In these gatherings, residents debate issues face-to-face, vote by a show of hands or by paper ballot, and take part in a tradition that has been described as the "purest form of democracy."

The importance of these meetings extends beyond local governance. They serve as a critical tool for education in civic responsibility, offering residents, especially the youth, a firsthand experience of democracy in action. The process encourages transparency, participation, and a deep sense of belonging to the community.

Rather than viewing the chaos of U.S. government and elections as a sign of dysfunction, we should recognize it as a beacon of hope in a world increasingly veiled in authoritarianism and apathy. The noise, conflict, and public debate that characterize American democracy are not weaknesses but expressions of its vitality. In a global landscape where many nations face oppression, silence, and one-party rule, the loud, sometimes messy, democratic process of the U.S. shines as a reminder that freedom thrives on disagreement, participation, and the right to challenge power.

Democracy isn’t about efficiency. It’s about engagement.

Turn Up The Volume!

In contrast, Halifax’s current mode of governance seems allergic to public confrontation. The silencing of our democratic forums hasn’t led to a better-functioning council—it’s only deepened the disconnect between city leaders and their constituents. Democracy should rock. It should be messy. Because if we’re not arguing about the future of our city, are we really building one?

The next mayor of Halifax, whoever that may be, should take a page out of the old Halifax council playbook—and maybe even from the Co-op Era in Nova Scotia still embraced by the Park Slope Food Co-op’s democratic gospel. Let’s hold meetings when citizens can show up, not when most are stuck at work. Let’s invite the debates back into the public square and embrace the cacophony. After all, democracy isn’t about efficiency. It’s about engagement.

Bring back the long meetings, the passionate arguments, and the messy democracy. Halifax deserves a government that isn't afraid to argue—loudly and in public—about what’s best for its future.

In today’s age of polarization, it’s easy to see arguments as a threat to democracy. But what if the opposite were true? What if democracy, at its core, thrives on argument—on conflict, debate, and the kind of messy disagreements that force us to reckon with diverse perspectives? This is not just idle musing but a crucial consideration when we look at local governance, particularly in cities like Halifax, where voices from rural areas and the people concerned with cats have been quietly marginalized under the guise of efficiency.

The beauty of democracy is its inherent tension. Disagreement is not a flaw but a feature of democratic systems. When we suppress conflict in favor of streamlined decision-making or silence certain groups to maintain peace, we undermine the very fabric of what makes democracy resilient. Democracy needs to be messy because life is messy, and the governance of people cannot exist in a clean, polished vacuum. Instead, democracy thrives in the chaos of ideas clashing, where out of discord emerges consensus—not the consensus of a single dominant voice, but one that has been fought for, refined, and made stronger through rigorous debate.

Consider Halifax's own history of municipal squabbles

To get at the heart of what a lively, non-capitalist, non-efficient approach to democracy should look like, we need to embrace the internecine conflicts that naturally arise when people care enough to argue, loudly and publicly, about their community’s future. For Halifax, this means returning to the messy, raucous, and even sometimes absurd debates—yes, even about things like cats—that once defined city council meetings under the now politically shunned Mayor Peter Kelly.

In many ways, Halifax council’s transition under Mike Savage to a more “efficient,” quieter form of governance has sanitized the very essence of democracy. Efficiency has its place in private enterprise, but democracy? It’s inherently inefficient because it’s designed to involve everyone, especially those with differing opinions. And internecine conflicts, those fierce internal struggles, aren’t a bug in the system—they’re the system working as intended. Halifax council meetings used to run long into the night, with heated debates about the smallest of issues often reflecting larger, deeply held community values. In other words, democracy at its best.

A perfect example of how havoc-wreaking debate shapes democracy can be found in Halifax's past council meetings. Remember the great cat debate of the early 2000s? At first glance, arguing over whether cats should be allowed to roam free seems trivial, almost comical. But, in hindsight, this was about more than just felines; it was about community values—about responsibility, safety, personal freedom, and even ecological impact. It was about working on a shared vision of what we wanted our community to be. It was a Thing. The back-and-forth on this issue revealed the underlying tensions in how Halifax residents saw their relationship with public space and each other.

There was passion, yes, and even division, but that’s what democracy is. When you strip away the ability to argue, you strip away the soul of public discourse. Struggles, like these once-lively Halifax council debates, ensure that every viewpoint is aired, even the loud and abrasive ones. And it’s these noisy, long-winded, emotionally charged discussions that allow a community to truly see itself, flaws and all.

But what’s been lost in this rush to efficiency is the essential cacophony that democracy requires. Look globally at the headlines today—from France’s protests over pension reform to the political upheavals in the U.S. and U.K.—you’ll see democracies grappling with their own messy natures. The argument isn’t always comfortable, but it's necessary. They could be more efficient, but that would come at the cost of democratic engagement, where every member feels heard and valued.

Halifax, like all the communities caught up in the 1990’s amalgamation craze, with its sprawling geography of rural, suburban, and urban voters, could benefit from leaning into the mess of democratic debate. Instead of striving for sterile harmony, we should welcome the discord that arises when people from different walks of life, with divergent interests and ideas, come together. The rural voter’s concerns over infrastructure may clash with the urban professional’s desire for better transit, but it's in that very clash where solutions are forged—solutions that reflect a true community of communities, not just a monolithic urban agenda.

Democracy is, by nature, inefficient and argumentative because it’s supposed to be. If we stop fighting over things like cats—or sidewalks, or zoning, or taxes, or affordable housing—we're not fully participating in the process of deciding how our city should be shaped. Halifax council needs to return to the days when it wasn’t afraid of debate, when people showed up ready to argue passionately about the future of their community, and when those arguments, however loud or abrasive, were welcomed. But we can’t wait for government to do it. They never will. This is our job as citizens.

Let’s stop being afraid of it and start embracing it again. The future of Halifax depends on it.

We need to rediscover the political power of arguing. It is not only the act of raising voices that matters, but what those raised voices signify: a vibrant, participatory democracy. The path forward for Halifax, and perhaps for all democratic institutions, is not in silencing the 'unruly,' but in amplifying them, allowing the messiness to be a generative force rather than a divisive one. Democracy needs argument because, without it, we are left with something far more dangerous than chaos—apathy.

William M, "Boss" Tweed, notorious 19th century NYC political fixer, said "I don't care who does the electing, so long as I get to do the nominating". Like the electoral college this also seems like an oligarchic knee on the neck of democracy.

Municipal politics seems a lot more democratic; but, you're right, our voices could use a little more amplification than just when you MIGHT (don't hold you breath) see a candidate at your door at election time or taking part in a one off, well managed debate.

The question is whether any form of democracy always leads to some kind of soft-or-hard oligopoly--unless there is formal way for the "many" to overrule the "few" without restoring to some form of revolutionary violence. Nova Scotia could not be a better example of the principle at work. We are in a fully-throaded hard version of oligopoloy, where a very small group of elected officials, bureaucrats, and the rich, are the ones who are making decisions. Take the Coastal Protection Act. Passed by all three parties, and then Houston kills it. His decision, which he as never even bothered to offer some --any--feeble rationale for his decisions, Houston shows his complete contempt for the people of the province having an active role in civic life.

The "few" are not interested in the messiness of democracry, escept when it threatens to impepe their wealth-driven agendas. This tendency to oligarlicy is not a recent theory; Artistotle warned about this exact problem.

Whatever we do, making democracy better means setting things up in such a way that everyone has to participate in democratic debate. One of the ideas that has gathered much more momentum than I was aware of, the approach called "sortition." Under this system, people are chosen by lot to run the government for fairly short terms, like 2 years or years. The Greeks did not have what we would call elections. They chose by using this lottery process. The fact that I did not know that lottery was how the Greek "election" process works was written out of the history I had access to. It's easy to understand why any budding oligarchy would want to completely erase from history a method for picking leaders that would power into the hands of the many, instead of the few.

As I said earlier, I have been surprised to learn how much work has already taken place in various experiments in using some form of sortition. Take the recent Ireland referendum lealizing abortion. I did not know the process. The government appointed a group of people chosen at random,, maybe 100?, and provided them with he resources they needed to conduct a thorough public review of the evidnce, and then make a recommendation. The group met, listened, and recommended amending he Constitution to make abortion legal. The elected representitives were not legally required to enact whatever such a sortition might recommend, but in this case, the government accepted the recommendation.

The other idea I hafe been exploring is one that goes under many different names, but the most inclusive one is "assemblies" In most models, the assemblies are fairly small, 900-1000. In one model any member of an assembly can put a motion for some action forward. If that assemhbly votes to accept the recommendation, and the recommendation calls for action beyond the boundares of the assembly, then the proposal goes to some set of other local assemblies, depending on the reach of the proposal

I served on several criminal juries in DC, including one for first degree murder. I did another one where the defendant had tried to run over a police officer. I had to send a note to the judge to disqualify one of the jurors because she had violated the judge's instruction not to talk about the case with other jurors until deliberations. He knocked her off. Then one of the jurors refused to vote with the rest of us, and we went round and round for hours.

I came away from this jury experience telling people that serving on a jury was the most democratic exercise of power that we have. Think about it: our whole judicial system is set up so that we give 12 randomly chosen people the right to rule on intensely complicated cases, and except in rare occasions, we all agree to abide by whatever the jury decides. I now see how the power we give to juries is the power we need to give to ourselves. I am wandering through ideas about a long-term strategy focused on a radical devolving of decision-making, working through the institutions we have to work withl. A daunting challenge. But I've been pretty deep into the belly of the electoral based oligolpoly-spawning first-past-the-post system we use to elect people who are then said to "represent" us.