Canada’s Bilingualism Experiment Has Failed—Now What? - Fluency, Fiefdoms, and the Fallacy of Canadian Bilingualism

We're immersed in something all right. For all our talk of inclusivity, the path to power in Canada is open only to a select few—and language, not merit, is the key.

Mark Carney’s French—fluent by most standards but imperfect by the impossibly high bar of Canadian political expectation—became the talk of the town following his debate performance. The former Bank of Canada governor, IMF veteran, and arguably the most qualified prime ministerial candidate in 80 years found himself “under scrutiny” not for his economic policies or leadership credentials, but for a linguistic slip.

This breathless morning-after the candidate’s debate news report linked below is typical. Unless a candidate can speak with the insider elite bureaucratic beltway French/English style, they can’t aspire to lead our country. It’s a modern Canadian equivalent of the old-fashioned classism found in British and French Eurocentric societies, where accents determined social status and career prospects. Just as the Received Pronunciation in Britain or the Parisian accent in France marked the “proper” way to speak, Canada’s bilingual elite has set an exclusive linguistic standard that shapes our political class.

In Canada, the unwritten rule is that a prime minister must be fluently bilingual—no exceptions, and very little leeway. But fluency, as defined in the elite bureaucratic beltway between Ottawa and Montreal, is not just about communication; it’s a gatekeeping mechanism that effectively disqualifies vast swaths of the population from even dreaming of national leadership.

By The Numbers

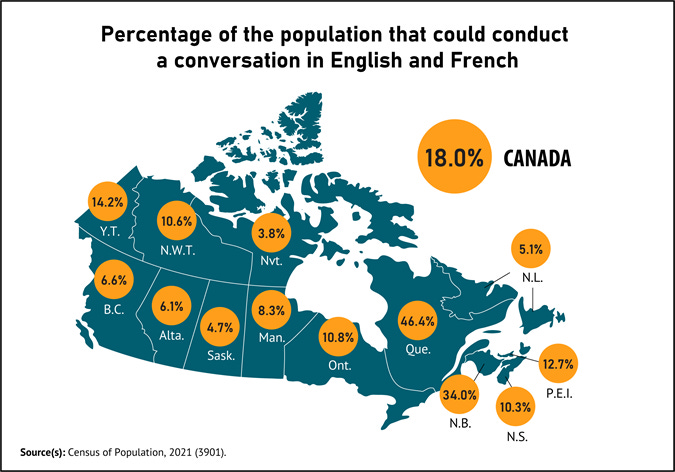

Few among us are raised to imagine being Prime Minister, holding public office, or even a federal government job in Canada. The most recent statistics report over 71% of Canadians do not speak French at all. Although 18.1% of Canadians self-report as bilingual in English and French, true fluency—measured by the federal government's rigorous language tests—would likely disqualify at least half of them. That means only about 9% of Canadians could meet the fluency standard required for high-level federal jobs. With 91% of the population effectively barred from federal jobs and office - it’s a structural filter that excludes the vast majority of Canadians from leadership, including the role of Prime Minister.

TIMELINE:

1969 – The Official Languages Act established English and French as equal and promised a bilingual federal civil service and government.

1988 – The Act is strengthened, making bilingualism more entrenched in public service.

1990s-2000s – Federal job postings increasingly require bilingualism for advancement.

We’ve been working at this for over 55 years. How’s that working out for us?

From the early 1960s to the turn of the century, the reported rate of English–French bilingualism in Canada rose from 12.2% in 1961 to 17.7% in 2001. Since then, the proportion of the Canadian population who is bilingual in English and French has been flat. But even that 20-plus years of languishing belies the fact that STATSCAN’s detailed reports show the rate of bilingualism outside Quebec has actually gone down but is offset by the number of French speakers in Quebec becoming bilingual.

To clarify - after over five decades of effort and billions of dollars of bureaucracy bilingualism is going down significantly in English Canada and it’s increasing in Quebec but only by virtue of the number of exclusively French speakers declining as bilingual numbers increase… the opposite of the intended goal.

STATSCAN REPORT ON FIVE DECADES OF BILINGUALISM

The bottom line is, outside of an elite educated economic class, mostly in the Ottawa - Montreal beltway and a few rarified enclaves in Canada’s cities,

91% of Canadians are excluded from higher office and federal jobs.

The reality is that this linguistic requirement means that almost no one outside of a small political corridor can rise to the top, shutting out most voices from the West, the Atlantic provinces, indigenous leaders, new Canadians, and much of English-speaking Canada. In a time when our demographics are shifting, our technology is evolving, and our regional interests are more diverse than ever, it's time to ask: Should bilingualism still be a purity test for leadership? And if so, at what cost?

French-English bilingualism in Canada has little to do with culture or national unity and everything to do with maintaining a bureaucratic elite. The dominance of French immersion in Atlantic Canada’s urban centers reveals that it is not a cultural necessity, but a strategic advantage for those who can access it. If Canada wants to be truly equal, it must rethink how bilingualism is enforced, accessed, and rewarded.

Je ne parle pas français au-delà des cours du collège et des voyages de travail en France, où je peux commander mon déjeuner sans trop de difficultés. Une fois, j'ai passé une matinée difficile à chercher mon chemin vers la gare avec mon sac à dos à Nice. Je demandais des indications, mais je n'obtenais que des regards vides. Finalement, une femme aimable m'a souri et m'a dit avec un accent RP parfait que je lui demandais mon chemin vers la guerre.

Mais aujourd'hui, la traduction est fluide en texte et presque à un niveau d'IA, où les conversations entre toutes les langues peuvent être traduites en temps réel avec rien de plus qu'un iPhone et un écouteur.

Here Comes a Real-Time Technology Solution

The paragraph above about getting lost on my way to “the war” is a real-time AI French translation using a free version of one of the dozens of breakthrough and surprisingly cheap translation technology apps and gadgets coming onto the market to make you a walking UN translator.

Now, technology is making language barriers irrelevant. AI-driven real-time translation, automated speech tools, and digital communication will soon make it unnecessary for a PM to be personally bilingual.

Instead of limiting the leadership pool with a colonial-era bilingualism requirement, Canada could embrace technological solutions that make government more inclusive, efficient, and accessible for all Canadians.

French-English Bilingualism as an Elite Gatekeeping Mechanism: The Case of French Immersion in Atlantic Canada

Mcleans Magazine recently reported plainly, that French-English bilingualism rates may be on the decline in Canada, but when it comes to getting kids into French immersion programs—which have come to be seen by many as a free private school within the public school system—there is nothing, it seems, that a Canadian parent won’t do.

French-English bilingualism in Canada has, intentionally or not, become a tool of class and elite gatekeeping. Nowhere is this clearer than in the popularity of French immersion schools in the cities of Atlantic Canada, where access to bilingual education creates a two-tiered education system that disproportionately benefits urban, upper-middle-class families while sidelining rural, working-class, and Indigenous communities.

While officially, bilingualism is framed as an issue of national unity, in practice, it has created a pipeline for political and economic privilege that ensures access to high-paying federal jobs, promotions, and leadership roles remains in the hands of a linguistically groomed elite.

The Hidden Class Divide of French Immersion

French immersion schools in cities like Halifax, St. John’s, Moncton, and Fredericton have become an unofficial sorting mechanism for future politicians, bureaucrats, and professionals. But this education model disproportionately benefits the children of government employees, professionals, and the upper-middle class, families who can afford tutoring and enrichment programs, and students with highly involved, educated parents.

At the same time, French immersion is notoriously inaccessible rural students with no local French immersion option, children from lower-income or working-class families who lack educational support at home, students with learning disabilities, who are often “counseled out” of immersion programs, and indigenous and immigrant students who are already balancing multiple languages.

French immersion has become a “good parent” rationalized elite pipeline, ensuring that the children of bureaucrats, civil servants, and professionals secure future high-paying government jobs, while working-class and rural kids are left behind.

A Bilingualism Requirement That Few Can Meet

The most valuable bilingualism in Canada is not everyday functional French—it is bureaucratic French. The kind that allows someone to pass the rigid, government-mandated bilingualism exams - Second Language Evaluations (SLE), which measure abilities in reading comprehension, written expression, and oral interaction. The proficiency levels are categorized as A (beginner), B (intermediate), and C (advanced). For instance, a position with a linguistic profile of BBB would require a candidate to achieve an intermediate level in all three skills. speak fluently in government meetings, legal settings, and in high-level negotiations.

This creates a structural bias where those who attend elite French immersion programs from childhood have a massive advantage. Students who learn French later in life or outside immersion programs almost never reach official bilingual status. Anyone from a working-class, rural, or immigrant background who didn’t grow up with privileged access to immersion is effectively locked out of many top jobs.

The federal government, the judiciary, and even the CBC favor an elite class of bilingual professionals who have had access to specialized education from an early age.

Atlantic Canada: The Growth of French Immersion in a mostly Non-Francophone Region

The paradox of French immersion in Atlantic Canada is that the region is overwhelmingly Anglophone, yet French immersion thrives in urban areas as a career investment strategy for ambitious families.

Halifax: ~12% of students in the HRM are in French immersion, significantly higher than in rural Nova Scotia.

New Brunswick (Canada’s only officially bilingual province): French immersion is often seen as a path to power, as top government jobs require French fluency.

St. John’s & Charlottetown: Demand for immersion programs exceeds supply, leading to lottery-based enrollment in some cases.

Despite no historical necessity for French in most of these communities, upper-middle-class parents push their children into immersion programs because they know bilingualism is the ticket to federal employment. It provides an edge in scholarship and university admissions and it signals social status, as immersion is associated with academic excellence.

In an overwhelmingly English-speaking region, French immersion has less to do with culture and more to do with careerism and exclusive class mobility.

Rural and Indigenous Students Are Systematically Left Out

In rural Atlantic Canada, French immersion programs are often unavailable due to a lack of resources or only accessible through long commutes or relocation. Rural immersion is not prioritized because local economies do not require French

Meanwhile, Indigenous students are actively discouraged from prioritizing French because they are already balancing English with their own Indigenous languages. They are more likely to be in rural areas with no immersion options and excluded from the elite bilingual pipeline that leads to government careers.

While urban, upper-middle-class families strategically enroll their children in immersion for career advantage, entire rural and Indigenous populations are cut out of the system—further reinforcing social and economic inequality.

Federal Job Distribution: How Bilingualism Keeps Atlantic Canada Dependent on Government

Atlantic Canada has a disproportionate reliance on federal government employment. The French language requirement for these jobs ensures bilingual urbanites from immersion programs dominate federal hiring. Unilingual working-class Atlantic Canadians remain dependent on lower-paying private-sector jobs. The region remains politically tied to federal policies because government employment is an economic driver.

Bilingualism serves as an economic filter, ensuring that only those who have passed through the immersion system gain access to stable, well-paid federal careers.

The Political Consequence: A Self-Perpetuating Elite

Because bilingualism is a barrier to political leadership, French immersion in Atlantic Canada is also an investment in future political power. Urban Atlantic Canada aligns politically with the bureaucratic class, while rural regions remain disconnected from the federal power structure. French immersion funnels power into a small, privileged group, making government leadership more insulated from the realities of most Atlantic Canadians.

French immersion (sort of) inadvertently created class and cultural divides at schools across Canada

As affluent white families drive demand for francophone programs and immigrant diasporas urge schools to teach in other languages, officials and parents are (at best) struggling to redefine what equitable education looks like.

What’s the Alternative?

If bilingualism is to be a true national value, it must not remain an elite gatekeeping mechanism. Possible reforms:

Eliminate bilingual hiring requirements in non-essential federal jobs.

Abolish the bilingualism requirement for prime ministers and federal leadership.

Provide better French education for rural, working-class, and Indigenous communities—without forcing them into elite immersion pipelines.

Acknowledge the economic divide that bilingualism creates and offer alternative pathways to political and economic power.

French-English bilingualism in Canada has little to do with national unity and everything to do with maintaining a bureaucratic elite. The dominance of French immersion in Atlantic Canada’s urban centers reveals that it is not a cultural necessity, but a strategic advantage for those who can access it. If Canada wants to be truly equal, it must rethink how bilingualism is enforced, accessed, and rewarded.

Are We a Nation of Many Languages or One?

As demographics, culture, and technology changes, Canada faces a fundamental decision: Should it be a nation of many languages, or should it move toward a unified linguistic identity while respecting cultural heritage? Will we become a tower of Babel or a country of immigrants united by a sense of shared identity, purpose and practical common language?

The practical argument for a single national language is compelling. A common language fosters: National unity, Economic efficiency, Stronger civic identity, and Better global competitiveness.

However, historical, political, cultural factors, and really just habit make this a delicate issue. But after 55 years of a failed and deeply flawed experiment, should we not at least open ourselves up to a more pragmatic path forward? If handled correctly, Canada could shift towards a unified linguistic identity over time, while ensuring that cultural heritage is still respected and celebrated.

Many successful nations function under a single dominant language while maintaining multicultural identities. The U.S., the U.K., Australia, and Germany, for instance, all have strong immigrant communities but operate under a single linguistic framework for governance, education, and public life.

Reality Check: Right now, Canada’s bilingualism laws require vast government resources to maintain translation services, bilingual hiring, and duplication of federal materials. This does not exist in most successful nations.

Reality Check: In the EU, multilingualism is a necessity because of cross-border nations. If we are a single country Canada does not need to function like the EU—we can be a nation, not a coalition of separate nation-states.

Reality Check: Canada is one of the few countries in the world where linguistic division has led to political fragmentation (Quebec separatism). Many successful countries have one language but allow regional dialects and heritage languages to flourish privately.

Reality Check: The U.S., Australia, and Germany all have strong immigrant communities that retain their culture and language—but governance is done in one national language. This strengthens national identity while preserving heritage.

A More Unified, Practical Canada

The two-official-language system is an artifact of 19th-century Euro-centric politics that no longer serves a modern, global Canada.

A one-language national framework (with protections for cultural heritage) would: Reduce bureaucratic inefficiency, Strengthen national identity, Encourage practical multilingualism (rather than colonial-era bilingualism), and Remove arbitrary barriers to leadership.

Canada must decide: Are we a country that prioritizes national unity and efficiency, or are we stuck maintaining an outdated linguistic divide that prevents true Canadian-first identity?

A Single Language Policy Can Be Argued from Any Ideology

Socialist/Left Argument:

A single language reduces class barriers, strengthens national unity, and makes government more efficient.

Language division is an unnecessary bourgeois construct that benefits elites, bureaucrats, and politicians at the expense of the working class.

Conservative/Libertarian Argument:

A single language shrinks government, reduces regulation, and prioritizes individual choice.

Government should not enforce bilingualism, and market forces should dictate language accessibility.

In both ideological frameworks, the end goal is the same: Canada should move toward a unified working language while allowing cultural heritage to flourish privately.

A Practical Approach

The real question is not whether Canada is a bilingual country or not, but whether it makes sense to maintain government-enforced bilingualism at all levels.

The best approach is likely a hybrid model:

Government shifts toward English as the default working language.

French remains protected in cultural and educational contexts, particularly in Quebec.

Bilingualism in leadership becomes optional, not mandatory.

Citizens remain free to use whatever language they want in private life.

This keeps government efficient, strengthens unity, and allows cultural diversity to thrive without state enforcement.

The Key Question for Canada’s Future:

Do we want language policy to be a government-imposed framework, or do we trust individuals and communities to decide for themselves?

The unspoken truth about Canada’s bilingualism requirement is that it’s less about communication and more about control. We dress it up in the language of inclusivity and national unity, but in practice, it serves as an exclusionary mechanism, barring all but a select few from the highest offices in the land. And yet, challenging this status quo is nearly impossible—because even questioning it invites accusations of anti-French sentiment, or worse, a betrayal of the very fabric of Canadian identity.

Parents, meanwhile, rationalize enrolling their children in French immersion not as a cultural choice, but as an economic necessity. They don’t do it out of love for Victor Hugo or a deep connection to Francophone heritage, but because they recognize bilingualism as a golden ticket—a way to secure future federal jobs, gain an academic advantage, and access a tier of opportunity otherwise closed to most Canadians. They will openly say it puts their children, and by extension themselves, in with a better class of people. It’s a system that rewards those who can afford the time, resources, and tutoring to navigate it, while leaving others behind in the race for the best, and even the ultimate federal jobs.

But if Canada is truly a modern, evolving nation, should it not be capable of revisiting its brittle old linguistic orthodoxy? Should it not at least consider a future where technology renders these barriers irrelevant, where national leadership is not dictated by a childhood spent in an elite immersion program? The road to change is murky, uncertain, and politically poisonous. But every reform begins with the courage to name the problem. The real question isn’t whether Canada should remain bilingual—it’s whether we are brave enough to admit that our definition of bilingualism serves as a gate rather than a bridge.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE BEE—In his book The Doubter's Companion: A Dictionary of Aggressive Common Sense, Canadian John Ralston Saul writes: "The citizen's job is to be rude—to pierce the comfort of professional intercourse by boorish expressions of doubt."

In this context, Saul emphasizes that citizens should challenge authority and question established norms. He believes that by disrupting the complacency of professionals and experts, citizens can prevent the concentration of power in dark corners and promote light. This active participation is essential for a healthy democracy, ensuring that different voices are heard and that those unelected influencers who have power through riches, intrigue, or office remain accountable to the people.

POSTSCRIPT

Just as I was finishing up this essay I got a media alert from the Wall Street Journal on the subject I was researching.

President Trump is planning to sign an executive order that would for the first time make English the official language of the U.S., according to White House officials.

In its nearly 250-year history, the U.S. has never had a national language at the federal level. Hundreds of languages are spoken in the U.S., the byproduct of the country’s long history of taking in immigrants from around the world.

Classic.

Yes, Trump is doing this. No, that doesn’t make it wrong.

Right on cue, Trump is signing an executive order to make English the official language of the U.S. And just like that, some will claim that the entire idea—regardless of its merits—is racist, reactionary, and elitist. But here’s the problem: the question of whether a nation should have a single working language existed long before Trump, and it will exist long after him. If we dismiss every policy idea just because Trump touched it, we surrender critical thinking entirely.

Making a single language official isn’t a radical right-wing idea—it’s how the vast majority of the world operates. France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, and even socialist Cuba and China function under a single national language. They do this not because they’re anti-multicultural, but because it makes governance, business, and national identity simpler and stronger. Ultimately, and for sure over five-plus decades of effort, it would give more people - a lot more - a chance at the good life, and an opportunity to represent the nation in public service.

Countries with multiple official languages like India, Belgium, Spain, South Africa, and Switzerland operate absurdly complex federal systems with extreme bureaucracy, instability, inefficiency, and division. They are all examples of how language policies become power struggles rather than solutions. Chaotic multilingualism fuels regional nationalism, separatism, and bureaucratic headaches across the globe.

Strangely, no one calls Quebec’s language laws racist, even though they are some of the most rigid in the world—banning English signage and restricting English education. No one accuses France of white supremacy for enforcing French as the sole language of government. Yet, when the idea of a single working language is applied outside Quebec or France, it’s suddenly the mark of bigotry? That’s not a principled stance—it’s pure political theater.

The question isn’t whether people can speak other languages—of course they can, and they should. The question is whether a country should function under one clear working language for efficiency, fairness, and accessibility. In Canada, bilingualism is not about protecting French culture—it’s about protecting an elite class that benefits from the system. A unilingual English speaker in Alberta or Newfoundland has less access to federal power than a bilingual Montrealer, no matter how qualified they are. How is that fair?

Forget Trump. If he weren’t involved, would the idea of a single national working language still make sense? Would it still reduce bureaucracy, open up job opportunities to more people, and strengthen national unity? If the answer is yes, then maybe we should debate the idea on its merits—not on whether the wrong person happens to be signing a piece of paper today.

Historically, a nation was defined by a common language. It facilitates communication and identity. Canada is neither united by a common language nor a single cultural identity. It has two official languages, but this has been a source of division, not unity. It has regional identities (Quebec, Alberta, the Maritimes) that are stronger than a singular “Canadian” identity. It never underwent the linguistic nation-building of France or Germany, instead maintaining a compromised and complex bilingual and cultural framework.

As we stand facing challenges and change pushed on us by Trump's tariffs, technological, economic, and cultural changes that further divide us and tear our traditions apart, it's time to unite in practical and fundamental ways or give up the notion that we are a nation at all.

The most interesting responses I’ve received privately since publishing this piece have been from people who have firsthand experience with both the regular public school system in Nova Scotia and the French-language school system—a system I hadn’t even realized existed in the way they describe it. And what they describe is fascinating: essentially a government-funded elite private school system with admissions based on race and cultural background.

Most people in the province know about French immersion, the program within English public schools where students can take their education primarily in French while still being part of the standard provincial school system. But there’s a second, far more exclusive system: the Conseil scolaire acadien provincial (CSAP), Nova Scotia’s publicly funded French-language school board.

Unlike French immersion, which is open to any student, CSAP schools are designed exclusively for children of francophone parents or those who can prove a strong cultural or linguistic connection to the French-speaking community. These schools operate with separate funding, separate administration, and separate admission criteria—and, according to those who have responded to my piece, they offer a dramatically better education than standard English public schools.

Here’s where it gets really interesting. Unlike regular public schools, where any student can enroll based on geography, CSAP schools have an openly selective admissions process. To be eligible, families must demonstrate:

Francophone heritage (having a parent or grandparent who speaks French)

A history of speaking French at home

A commitment to maintaining the French language and culture

This means that a child of English-speaking parents cannot simply apply, even if they want to learn French. But a child from a historically Acadian or francophone family gets automatic access to what is, by all accounts, a superior school system.

Those who have responded to my piece describe this as a racially and culturally exclusive admissions policy, one that quietly creates a two-tiered public school system where access to the better-funded, higher-performing schools is determined by ancestry.

This is precisely what I was arguing: bilingualism in Canada is not just an opportunity—it is a quiet form of gatekeeping. A ticket to better education, better job opportunities, and better access to government power—but only for those who meet the unspoken criteria.

It’s worth asking: if a parallel school system existed for another group—let’s say, children of Scottish or German descent or Catholic—would it be tolerated... or funded!? Would it be defended? Would it even exist?

The fact that this system is not widely discussed is revealing. And now that I know about it, it further changes the way I see the entire conversation around bilingualism in Canada.

A lot of good points in this post. One question is: what is language? I learned "Parisian" French in France, where there are many distinct regional accents. Partly while living with a family, taking classes at a small institute, smoking cigarettes, drinking coffee and cheap wine and watching the TV news where the newscasters speak in carefully articulated Parisian French. After all these years, my ear gravitates to it.

Meanwhile, all countries have many varieties of the native tongue. English in Canada has many regional varieties, including vocabulary and argot/slang. So does French in Canada. Driving through Quebec and NB, most of the time my Parisian friends did not think they were hearing "real" French. These regional differences make a mockery of the notion of linguistic purity. All big cities have many versions of the so-called native tongue. Try walking the streets of Boston or New York, Toronto or Montreal -- it can vary block by block, even among so-called educated speakers. Influxes of immigrants change it up, as they always have.

My Norwegian father came to Newfoundland and then Canada after WW II. He had learned English in London in the 1930s and made fun of the snobbery that kept the top jobs for those whose accents indicated they had attended the right schools. By a fluke he had gone to one of them as a scrawny young teenager who at first spoke no English. Relatives on both sides of my family speak multiple languages, partly from living in different countries when they were young. On my father's side, barely surviving both the Russian Revolution and the Nazi occupation of Norway (my uncle practiced his German in Buchenwald, where he also spoke English and Russian.) On the other side, as girls my grandmother and her sisters lived in France, Italy and Germany, and for a brief time in Spain, so they could learn the languages, peregrinations that were affordable in pre-World War II Europe. Although these experiences were not easy, they made the girls open-minded, always ready for the next adventure.

In much of the world, English is the de facto second language. In many places you can hear five people from five countries getting along fine in their various forms of imperfect English. Languages spread along with trade, exploration, and conquest. My father went on one of the first foreign trade missions to China in 1974, after Nixon opened it up. Although he was anti-communist from experience as well as philosophy, he could sense the gradual rise of that massive country. "Forget French," he said. "Teach your children Chinese."