Canada Post's Fate Is Signed, Sealed, and Delusional

The OG Public Sector Union. It's time to Return to Sender. Why Canada Post Is Striking Again — And Why It Might Be Time to Shut It Down.

Herodotus, the Greek historian writing in the 5th century BCE in The Histories, describes the Persian postal system under King Xerxes, which was remarkably fast and reliable for its time:

"It is said that as many days as there are in the whole journey, so many are the men and horses that stand along the road, each man and horse at the interval of a day's journey. And neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor darkness of night prevents these couriers from completing their appointed course with all speed." — Herodotus, Histories 8.98

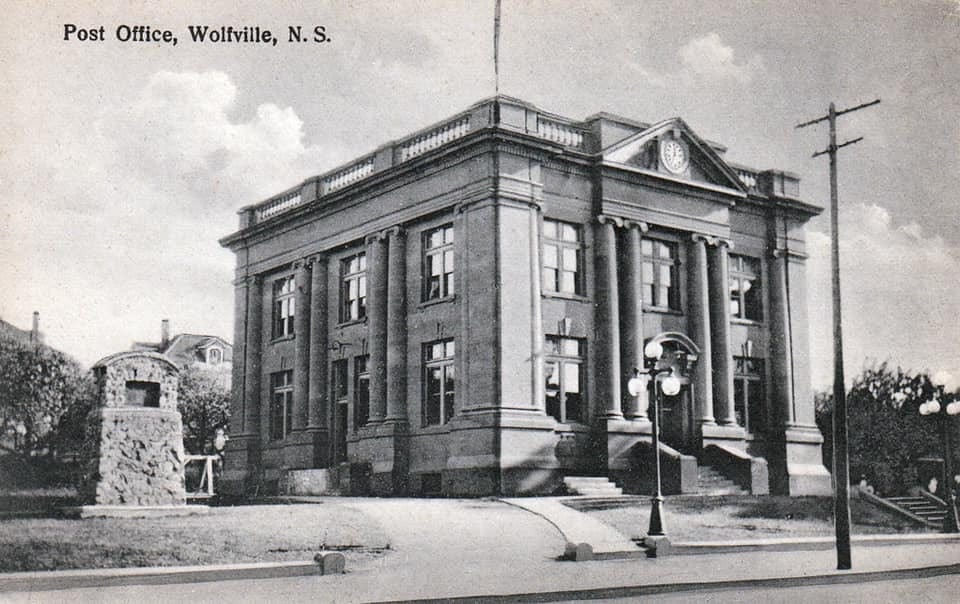

The phrase was modernized by architect William Mitchell Kendall of McKim, Mead & White, the firm responsible for designing the James A. Farley Post Office in New York City, completed in 1914. Kendall had a love of classical literature and chose the inscription for the grand façade of the building.

The phrase was carved in stone on the front of that building—still one of the most iconic U.S. postal buildings. While not an official motto, it has come to symbolize the idealized dedication of mail carriers.

Ironically, the mail has often been delayed by snow, rain, heat, and strikes— goodness knows the postalworker is not stepping in our yard if the driveway is not shoveled clear and dry — but the phrase remains a symbol of civic duty, perseverance, and service, echoing a time when infrastructure and communication were feats of empire.

Today, with the rise of email, privatized courier services, and institutional decline, the phrase often reads more like an epitaph than a mission statement—especially amid recurring Canada Post disruptions and service erosion.

But like many old phrases, its power lies in what it evokes, not in what it guarantees.

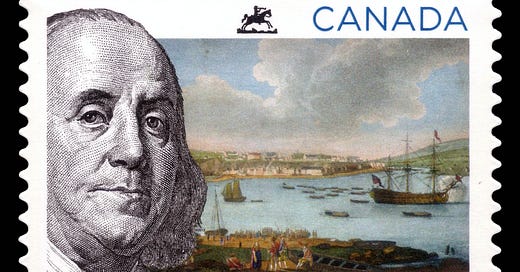

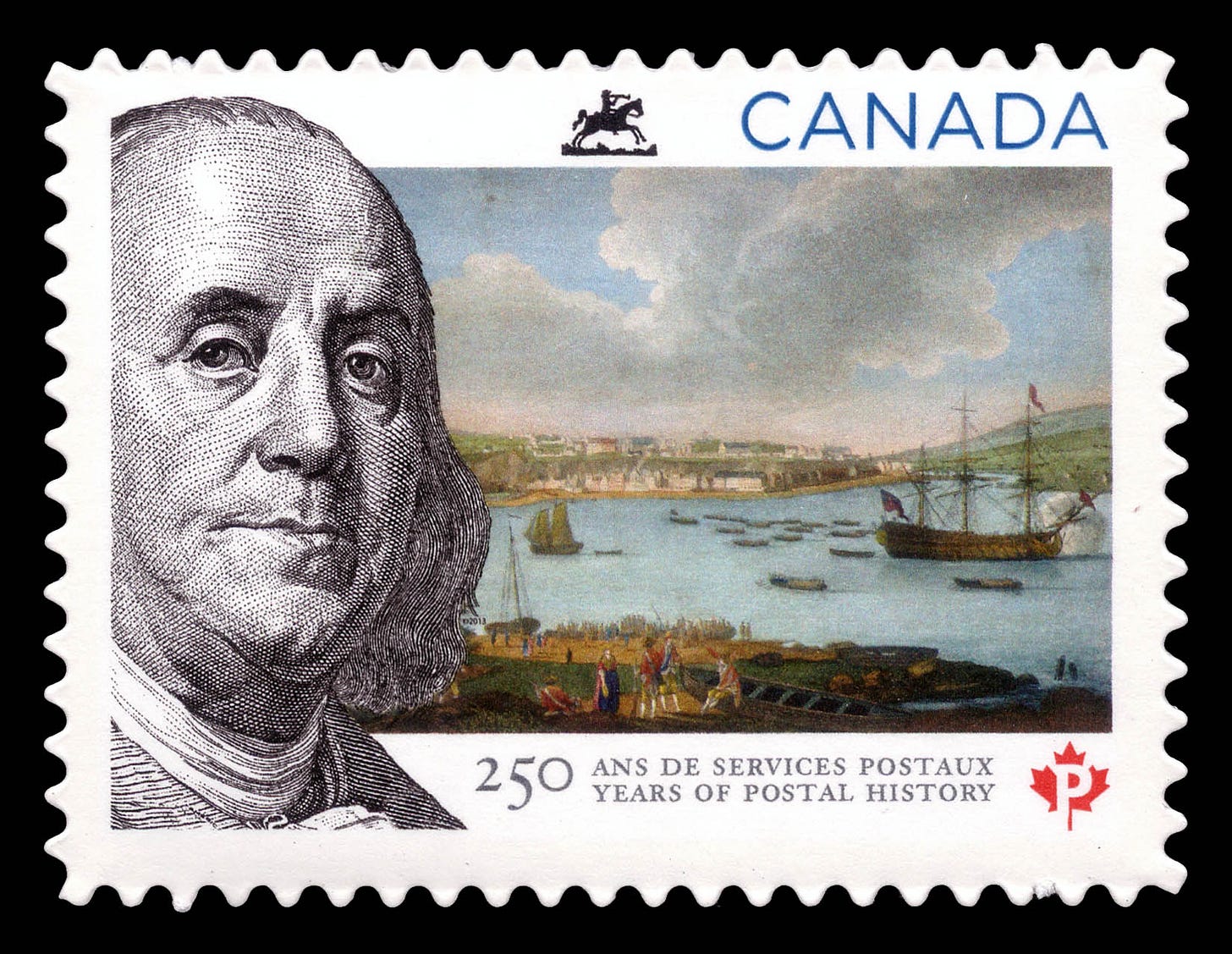

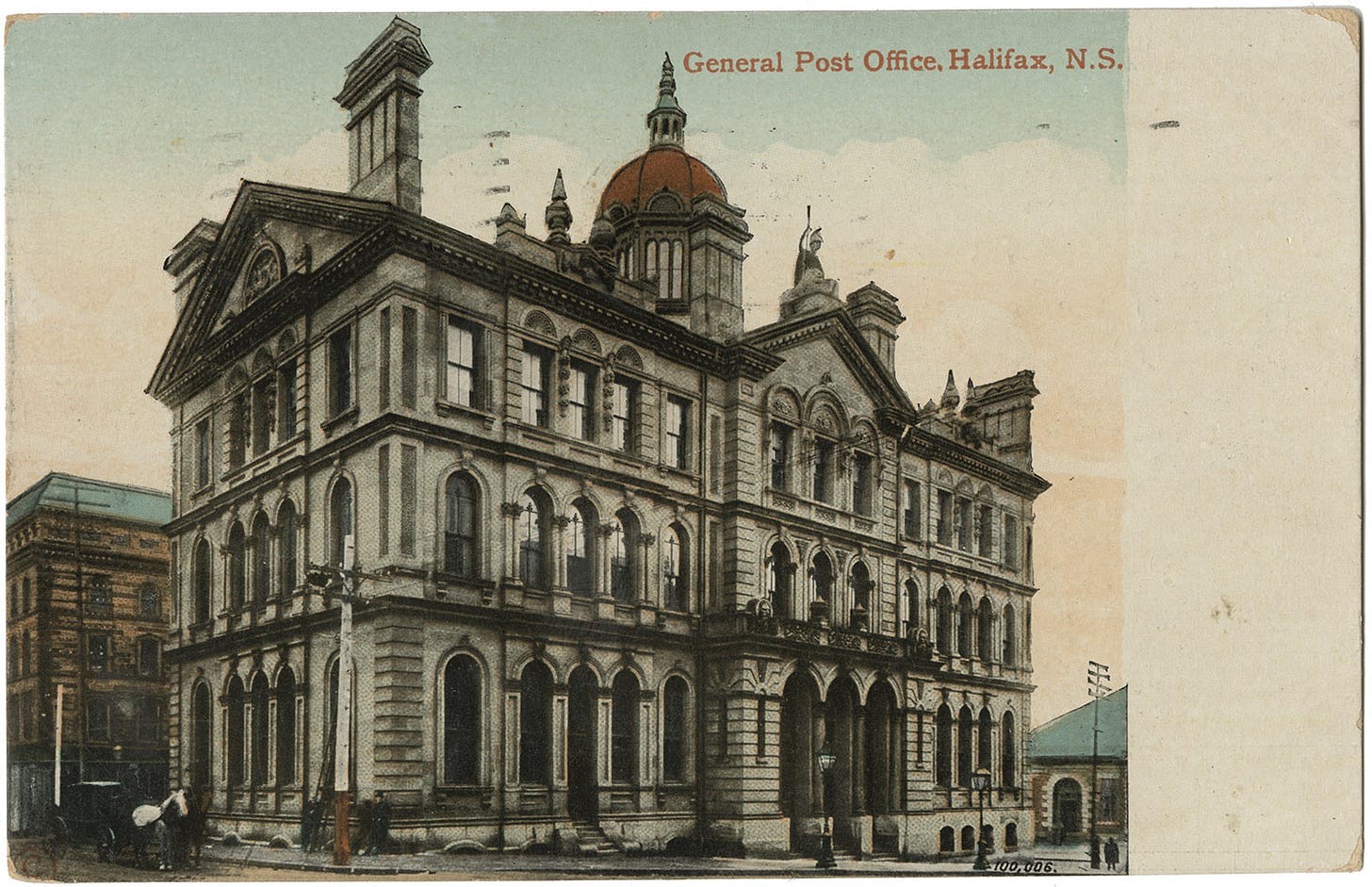

The first post office in Canada opened in Halifax in December 1755. It was Benjamin Franklin’s idea. Or more precisely, it was his job. As Joint Deputy Postmaster General for the British colonies, Franklin was tasked with stitching together an information network across wild distances, colonial rivalries, and hostile terrain. He understood that empires are held together not just by armies or taxes, but by letters. Ideas. Orders. Gossip. He didn’t just open the Halifax post office—he connected it to Boston, New York, and London. There’s no way to over blow the awesomeness of this. Imagine creating the internet, websites, email, Amazon, and international commerce and banking all in one go. And in doing so, he laid the first threads of the system that would later become Canada. We don’t hold ‘institutions’ in high regard these days. But some institutions, like ‘em or not, are what history was made from, and much of what we enjoy today was built on this once inimitable monopoly.

Canada Post has received strike notice with workers set to walk out on Friday.

The facts were presented to CUPE members by an industrial commission of their peers who made it clear — Canada Post as it was is over.

But the delusion continues both within CUPE and government. This time, it really is up to citizens to call it a day.

By Confederation, the post office wasn’t just a convenience—it was the state. Fro most, the post office was the government. Besides collecting customs, maintaining militia muster rolls, and keeping up a modest naval presence, the early Canadian government’s real tangible offering to citizens was the mail. You could be in the middle of the woods, and somehow a letter would find you. That magic—paper, ink, stamps, a whistle in the distance—was what stitched together prairie homesteads, Cape Breton fishing coves, and rail towns in the Rockies into something that could be called a country.

In the 20th century, Canada Post expanded with the same force and faith as the railway or CBC. You could mail a cowbell from Dawson City to Halifax for the same rate as mailing a wedding card across town. It was absurd and beautiful. A shared cost for a shared country. But as the post office grew, so did its payroll—and with it, eventually, the power of the public sector union.

The 1970s brought more than Pierre Trudeau and metric. They brought the postal strike era—brash, ugly, and frequent. Letter carriers became national punchlines and unlikely heroes. Some days they marched for better pay; other days for shorter routes or longer breaks. As trade unionism declined the idea was transmuted and its ghost possessed the public sector. But behind the picket signs, Canada Post became the vanguard of a rising public sector, where job security trumped service, and negotiation meant disruption. Trade Union traditions of little guys getting together to stand up to robber barons for good working conditions, fair pay and decent lives was awkwardly grafted on to a system where the titan of industry was the Canadian taxpayer and the very same government employees calling for lower taxes and smaller government were calling for high wages and more concessions. It’s an unsolvable riddle that causes a kind of social insanity in any nation it infects.

Then came the phrase we all remember but no longer use: “going postal.” Born from American headlines but felt here too, it reflected the boiling frustration inside a bloated system: high pressure, low purpose, zero adaptability. Every organization has a kind of culture and consciousness apart from the individuals that make it up. And that culture attracts the kind of people who would flourish in it and perpetuate it. IT’s a logic of all living organisms. The post office had become the home for those who belonged there, and the consequences were sometimes tragic. almost everyone who I’ve know who worked there during these years has died deaths of despair.

SIDEBAR: Going Postal - The Rise and Stall of Canada’s Postal Union

1950s–1960s: The Public Sector Awakens

1950s – Most Canadian public servants have no formal bargaining rights. Wages and working conditions are set administratively.

1967 – Public Service Staff Relations Act grants federal workers the right to collective bargaining. This marks the true beginning of modern public sector unionism in Canada.

1970s: Postal Workers Lead the Way

1968 – CUPW Formed: The Canadian Union of Postal Workers is created, combining earlier smaller postal unions.

1969 – First Legal Strike: CUPW launches its first legal strike. It sets a precedent for public sector workers asserting private-sector-style demands.

1970s–1980s – CUPW becomes one of the most militant and politically active public sector unions in Canada, often striking and pushing for broader social justice goals.

1981 – Canada Post Becomes a Crown Corporation

Canada Post is separated from the federal civil service, intended to operate on a more business-like footing.

Ironically, this change entrenches the power of the union, giving CUPW a single target (Canada Post) rather than the broader federal government, while still maintaining political leverage and public funding.

1980s–1990s: Militant Peak

CUPW strikes regularly. Postal service becomes synonymous with disruption.

"Going Postal" enters the lexicon—initially in the U.S., but reflecting mounting internal pressure and dysfunction in unionized postal workforces.

1991: A 2-week strike by CUPW over pay and job security disrupts national mail service.

2000s: Restructuring and Resistance

Automation, digital transformation, and competition from private couriers begin eroding Canada Post’s relevance.

CUPW resists job cuts and route restructuring, even as letter volume collapses and parcel delivery becomes king.

Strikes and rotating walkouts continue into the 2010s, despite declining public sympathy.

2018 – Backlash and Legislation

CUPW launches rotating strikes over forced overtime, safety, and pay equity.

The federal government passes back-to-work legislation, highlighting the limits of public patience with essential service disruptions.

2020s: Legacy Without Purpose

As mail volume plummets and costs balloon, Canada Post is functionally insolvent but remains heavily unionized.

The Industrial Inquiry Commission (2025) labels Canada Post as “effectively bankrupt,” recommending sweeping reforms—many aimed at limiting CUPW’s stranglehold on staffing and service models.

The union opposes the reforms, setting the stage for another round of disruption.

In sum: CUPW and Canada Post illustrate the broader arc of Canadian public sector unionism—rising from traditional unionism’s logic and legitimate demands for fairness, growing into a political force, and now standing as one of the greatest obstacles to reform in a public service that no longer serves.

In time, the monopoly cracked. In a capitalist system, problems this obvious begin to look like opportunities ever quickly. First came private couriers—Purolator, FedEx, UPS—cheerfully offering what the post office could not: certainty. Then came email, online billing, and bank apps. The core business—sending letters—fell off a cliff. Mail volume dropped by more than half between 2006 and 2020. But the pensions? The benefits? The dense layers of management? They didn’t drop. They swelled.

Today, Canada Post has no reason to exist. The parcel business is handled better by competitors. The legacy business—letters—is essentially extinct. And yet, tens of thousands of employees remain, paid with public money to operate a legacy infrastructure for a public that no longer needs it.

The cost? Billions. Canada Post lost $748 million in 2023. Last year’s operating expenses were $8.7 billion. And for what? For what?

The Industrial Inquiry Commission's recent report on Canada Post presents a stark assessment of the Crown corporation's financial health and operational viability. Commissioner William Kaplan describes Canada Post as effectively bankrupt with no business case for the future under the current structure, emphasizing that without immediate and significant reforms, its fiscal situation will continue to deteriorate.

For a detailed overview, you can access the full report and its key findings on Canada Post's official website Canada Post.

Let’s be pragmatic for a moment, just for argument’s sake. It might be cheaper to close it all down and simply pay postal workers a stand-by fee to stay home until their pensions kick in. Let them coach minor hockey and take up woodworking. The savings would be staggering. The pain, mercifully brief. The competitive market lightning fast to pick up the slack.

But the truth is more bitter: this isn’t really about Canada Post. It’s about a government that can’t let go. An anachoristic union that exists to grow and serve itself while the average citizen is cast as the robber baron. A nation that confuses nostalgia with necessity. And a public that quietly adapts while its institutions pretend nothing has changed.

Canada Post is an abomination, existing out of its proper place and time. Its past is undermined by its present. And what we see in it is not part of Canada’s future.

There are many things we need to grow Canada as a nation in the 21st century. Canada Post is not one of them. The future of this country will not be built by preserving relics of a bureaucratic past. The national project ahead of us is not a sentimental exercise in institutional nostalgia, nor can it be run by a self-serving, insider political force masquerading as a union. That era is over. It was hollow at the end, and expensive while it lasted.

Canada Post, as it stands, is a monument to inertia. Its purpose has dissolved, but its payroll has not. Its monopoly has evaporated, but its demands grow. It delivers fewer letters each year, but clings to a 20th-century worldview where empire equals infrastructure. The truth is harder, and simpler: the post office is not a vital service. It is a political job bank, sustained by fear, entitlement, and the unspoken agreement that no one will tell the truth if everyone keeps getting paid.

But the new Canada—the one we must now make—is a country of connection, not courier slips. It will be built not by preserving the machinery of yesterday, but by investing in the creativity, courage, and community ties of tomorrow. This new nation will be defined by what we build together, how we care for one another, and how we re-inhabit the places we’ve neglected. It will be grounded in physical presence, not the illusion of service. It will value real work, not make-work.

Canada Post is not only unnecessary to that vision—it is in the way.

It drains resources, clogs reform, and distorts what public service even means. And if we are serious about building a country that works again—for families, for creators, for doers, for those who don't punch the clock but build the clock itself—then we must have the courage to say: this institution had its time. Now we need different tools. Better tools. Tools that belong to this century.

Let the past rest. It delivered its final letter long ago.