Beareaucracy: Black Bear - Red Tape

The great black bear rehab debate wasn’t about science or safety. It was about something even wilder: how government expands itself when challenged.

Bear cub rehabilitation has been a controversial subject in Nova Scotia, most notably after an orphaned black bear cub was taken from Hope for Wildlife and euthanized in 2020.

When a simple ‘yes’ would have sufficed, the government chose a four-year ‘maybe’—and burned through hundreds of thousands of dollars deciding if bear cubs deserve a second chance.

Can we talk about Beareaucracy?

Soon after, Hope For Wildlife submitted a proposal to the provincial government asking permission to rehabilitate orphaned cubs. It was denied the following year.

The Houston government made a promise as part of its mandate when elected in 2021 "to provide options for regulated wildlife centres to rehabilitate orphaned bear cubs."

But the elected government has been unable to get the unelected government to follow through and it’s been four years of struggle.

In a January 2025 media release the Natural Resources Department told the CBC it is confident it will be ready "to provide permits to facilities" by the spring. Spring - the time of year mostly likely to see injured or orphaned bear cubs - is now 10 days away.

Nothing has happened yet.

What is the Natural Resources Department’s problem with bears?

In this Newsletter from THE BEE I’m also going to share with you the trailer from our first DOCUMENTARY - “Black Bear - Red Tape” which is available to our paid subscribers.

You can also watch HOPE FOR WILDLIFE, a factual TV series I created and produce on your favourite channels and streaming platforms. This month Season 11 is premiering in Canada on Blue Ant Channels and is available through April in Free Preview.

The Backstory

When I was a kid I was involved in a dramatic Black Bear encounter that made me hate Black Bears for many years. In fact, some part of me still bears a grudge against bears.

I was one of those kids who liked to carry a blanket - Linus style.

But mine was more elaborate. It was an unbleached and faded flannel with horses and ship’s wheels in a pattern. Maybe it was once a nursery curtain or some homespun something from the long-gone baby basket.

One day while out picking blueberries in a vast barren with my Grandmother, I wandered away from our little campsite, my grandmother, and my blanket. It was the kind of day that the sun warmed the ground and it radiated up all the smells and warmth of the earth. I was exploring some footpath through the tall grass that led to the edge of the dark treeline - a sharp jag of deep greens - the balsam fir and red spruce that make the dense, nearly impassable thickets, especially in regenerating forest stands in Nova Scotia. Unable to go further I turned and started back to our little day camp near the road in the big field.

When I got there the picnic basket, thermos, and cups were strewn. My Grandmother, and my blanket, were gone!

It seemed like an eternity but it was probably just a heartbeat until I saw my grandmother coming over the top of the field with our blueberry boxes full. But she didn’t have my blanket. She looked at me with some alarm. There’s no doubt I was rattled. Everything rattled me in those days. And ghastly pale has always been my perpetual complexion unless stroked scarlet by an hour in the summer sun no matter how cold the coastal wind. I was probably a mix of both puffed-eyed as a Johnny Cobbler on the wharf by the tears that I can still to this day sob cartoon style like a maudlin fool.

I was apoplectic. We searched frantically as she packed up the car. Finally, with the day getting near supper, and having searched everywhere, my grandmother put voice to my worst fear… a bear must have taken it. She was grave, calm, and serious. “We should go.” she said quietly. And, even through tears, I was sure she was right.

I had only just pulled it together by the time we got back to her old house near the coal mine where my Mom was making supper. In those days in Pictou County supper meant burning a quarter-inch slice of meat those of us not knowing any better called “Steak” and mercilessly boiling whatever vegetables that weren’t obviously moldy into a kind of paste - but not the fluffy mashed potato kind - but lumpy and with turnip or whatever other hard vegetables that survived the winter in the cellar mixed in.

But I lost it telling my mom the story; my high and hollow vibrating voice giving way again to a theatre of emotion. The bear had taken my blanket. It was, by a wide margin, the biggest most terrible tragedy I had personally faced up to that point in my life. I was in a shambles.

Now, reading this you probably wonder, and if I told you my age at this point, you would for sure think I was too old to be this dumb. But I wasn’t! I’m still not. I just can’t bring myself to not believe something I’m told to my face.

Reckless with misery, somehow I didn’t see any of the nods or winks, the knowing smiles, or the over-the-top pity I was being shown for my grievous loss. I wasn’t even forced to eat the supper. They gave me white bread with molasses and sugar on it and let me go sit on the back step with the scarred old barn cat, who I’m sure harboured awful secrets of her own far worse than my calamity. I told her the story and I told myself to calm down as she looked at me skeptically with her good eye.

I went almost twenty more years telling the story of the Black Bear taking my blanket to friends and people I met in deadly earnest - solemnly describing that blanket even as it faded more from memory. The story got better and better over the years as stories do in Nova Scotia. Eventually, in the story, I could see the big bear taking the blanket and almost eating my Grandmother before my coming up the footpath must have scared it off.

I was almost 30 years old and telling the story to some hunters at a dinner at the Mason’s Lodge, when it dawned on me… there was no bear. My Grandmother had taken me out to the woods and done the heavy lifting of getting rid of the blanket that was clearly, in our family circle, becoming a real problem and embarrassment. I had heard the grumbling. But I just never imagined this.

It could have been worse. I’m sure my grandfather’s strategy to deep-six the blanket would have been far less clever, and a lot more painful.

Still, almost 20 years of telling anyone who’d listen all about my face-to-face and terrible bear encounter.

Man, I hated those bears. Being in Nova Scotia, where the height of conversation really just involves swapping like or similar stories - listening patiently to one person to earn your opportunity to tell your story - it never surprised me to find that my eye-rolling audience always seemed to have their own bear story. I’ve probably heard a hundred of them. Or maybe I should say the one story, told a hundred times over. Though the places and details change the story goes like this… I saw the bear and the bear saw me. I ran one way and the bear ran the other. There may be other bear stories in Nova Scotia but over hundreds of years, a million people, and ten million acres of forest, there aren’t very many that differ.

So now I look at the bear from the other side of the mountain. To tell the truth, as if I had been prompted to lie about it now, I know the bear issue is polarizing because of the stories we tell about them, and the notion that it is the bears who have taken something of ours, when surely it is the other way round.

Black Bears in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia black bears are a barometer for the health of our forests and our concern for the environment. Published research proves that orphaned bears can be safely rehabilitated and released. It’s just the right thing to do.

So let’s get a few facts on the table and identify the unknowns.

Seeing a bear is not a bear attack or an 'incident'.

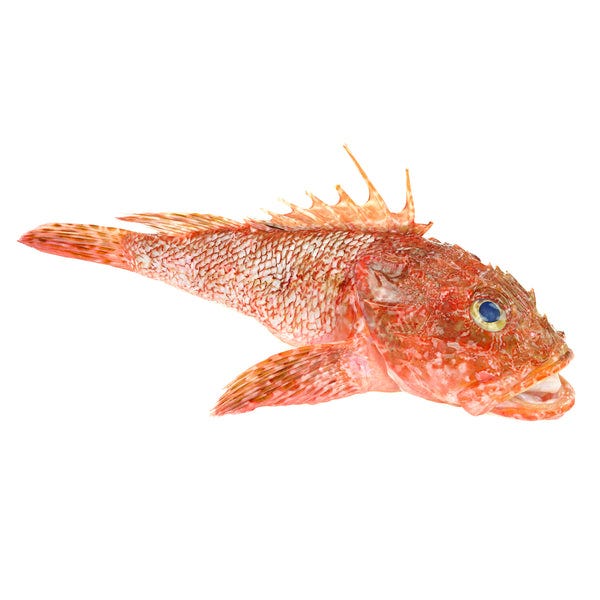

The only bears in NS are Black Bears.

Number of black bear attacks in Nova Scotia ever - 0

Number of people killed by black bears in Nova Scotia ever - 0

The number of Black Bears in Nova Scotia is a complete unknown. It is estimated from the number shot by hunters and the number killed by cars… and DNR… along with a made-up estimate that these might about for about 5% of the population. You don’t have to know much about math or statistics to know that that’s wrong thinking.

Nova Scotia has over 10 million acres of forest away from everyday human presence.

Nova Scotia’s commoditized forest bureaucracy should stop using fear to justify killing bears and other wildlife just because they've inconvenienced and exposed their poor forest and waters management.

Care of the earth is our most ancient, most worthy, and most pleasant responsibility. To cherish what remains of the wild world and seek its renewal is our only hope for the future and our only meaningful legacy to rising generations.

Here's a joke.

Why did the bear cross the road?

Because the road crossed the bear’s forest.

It’s not bears that we need to change, or any other wildlife, it’s our own bureaucracy.

If you want to know what the Department thinks of Balck Bears you can read it directly from them here on the government website...

For A Different Perspective, We Can Talk To Basically Anyone Else In The World

Nova Scotia sees - at most - about a half dozen injured or orphaned baby black bears each year. Some years there are none. These animals are emblematical of how we think of our forests, waters, and wildlife. And they represent the first - they want nothing to do with us.

Here’s Dr. Martyn Obbard, a Research Scientist with the Wildlife Research and Development Section, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources based in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, and an Adjunct Professor in the Environmental and Life Sciences Graduate Program at Trent University in Peterborough. Martyn has studied black bears in Ontario since he joined the Wildlife Research Section of OMNR in 1989. Martyn has been involved in several long-term black bear research projects—in the boreal forest (1989—2001), on the Bruce Peninsula (1998-2006) and in Algonquin Park (2006—present). These projects have focussed on black bear demographics, effects of hunting, habitat use, denning requirements, effects of forestry, and human—bear conflicts.

The point here is the work is done. We know A LOT about Black Bears.

Where other provinces and states with Black Bear rehabilitate them in privately funded sanctuaries and successfully return them to the wild, in Nova Scotia, most often, they are taken by the government and shot.

The Four-Year Farce: How Nova Scotia’s Bureaucracy Blocks Black Bear Rehab—And What It Says About Government Failure

Four years ago, the Premier of Nova Scotia gave a clear directive: get black bear rehabilitation up and running. The logic was simple—Nova Scotia’s black bear population is small, non-threatening, and fully capable of being managed through the province’s existing, privately funded, world-class wildlife rehabilitation infrastructure. Hope for Wildlife, a globally respected organization with decades of experience, was ready, willing, and able to take in orphaned cubs at no cost to the taxpayer, no risk to the public, and with no real obstacles beyond basic regulatory approval.

And yet, here we are.

After four years of delays, studies, consultations, stakeholder meetings, and administrative roundabouts, there is still no black bear rehabilitation program in Nova Scotia.

The cost of the four-year delay in taxpayer terms is certainly substantial. Here’s a back-of-the-envelope estimate, which, even if it’s off by 80% is still ludicrous for work that is absolutely either already done or could be done with privately available funds.

If this is a hill to die on for anyone, I’m happy to share and show my work on these calculations. I have no access to departmental information, but I can estimate the time, labour, and contract costs based on media reporting and the years of work delaying this project.

A Manufactured Controversy

What should have been a straightforward policy decision—one already in place in other Canadian provinces—has been transformed into an expensive, bureaucratic boondoggle. Instead of implementing the program, the Department of Natural Resources and Renewables (DNRR) has engaged in complexification: the process by which government agencies take simple, solvable problems and make them endlessly more complicated through regulation, fear-based messaging, and institutional inertia.

To justify its inaction, DNRR has engaged in what can only be called a misinformation campaign. Officials have exaggerated the risk of black bear rehabilitation by spreading misleading claims about bear behavior, population density, and habitat capacity. The truth is that Nova Scotia’s black bear population is tiny by Canadian standards, with no evidence that properly rehabilitated bears would pose any more risk to the public than their wild-born counterparts. These are plant-eating, shy, forest-dwelling animals, not aggressive predators stalking suburban backyards.

Yet the bureaucratic response has followed a predictable script:

Conjure up a risk where none exists. Suggest that bears will become habituated to humans, despite the fact that provinces with rehab programs (Ontario, BC, Alberta, New Brunswick) have not seen any increase in human-bear conflicts as a result.

Insist that “more study is needed.” When faced with political pressure, launch new research projects and “impact assessments” that will take years to complete and conclude nothing new.

Slow-walk any real action. Promise that progress is being made while burying the process under layers of approvals, oversight committees, and paperwork.

The Bureaucratic Playbook: Delay, Distract, and Deny

What makes this case particularly infuriating is that Hope for Wildlife could have implemented bear rehab immediately, at no public cost, and with no additional infrastructure required. They have the land, the expertise, and the community support. But instead of simply saying “yes” to a proven, successful model, the government chose to say nothing while dragging the process out indefinitely.

This isn’t just a story about bear rehab—it’s a case study in how modern bureaucracies work against solutions, rather than for them.

The problem is structural. DNRR, like many government departments, operates in a siloed, insular way that prioritizes internal control and process over practical outcomes. The department’s interests are not aligned with the public interest or even the Premier’s directives. Instead, like most entrenched bureaucracies, it follows the path of least accountability and maximum self-preservation. Whatever the personal beliefs of the many, I’m sure fine and well-intentioned people working there, if it has any allegence at all it is to the ideology of a commoditized forest, where its highest and best use, its only use, is as a commodity crop to be sold or traded for the prospect of foreign capital.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

A problem emerges. In this case, orphaned black bear cubs in need of rehabilitation.

A solution is offered. Hope for Wildlife, a well-established, privately funded organization, steps up with a plan.

Government agencies panic. They begin raising hypothetical risks, demanding further study, and warning of “unintended consequences.”

The problem is turned into a long-term project. Rather than resolving it, the issue becomes a bureaucratic hamster wheel—meetings, reports, reassessments, all leading nowhere.

The public forgets, the government moves on, and nothing gets done.

And somehow out of all this the only action item has been, astonishingly, a proposal for a Spring Bear Hunt that led to some sort of (again costly) public engagement - as if the government and department doesn’t know exactly what people think about all this - before it was shut down by the elected government and abandoned because of the sheer volume of outrage the elected government was faced with.

Let’s not forget this one.

A Simple Fix, Blocked by a Broken System

Few issues so reveal the difficulty our elected representatives have in bringing the culture and ideology of too-powerful and siloed government departments into check. People ask why one government looks very much like the last but seldom think it through to the obvious answer - the bureaucracy doesn’t change when the government does. We can elect a representative on any mandate. But if they don’t have the power and support to change the government they become little more than spokespeople for the bureaucracy.

In this fascinating article Allan McMaster, arguably the second most powerful and most experienced elected representative after the Premier went public in pleading with the Natural Resources Department to stop killing the baby bear cubs that made national news. He was acting, based on personal values I would say, and on the demands of over 70,000 concerned citizens who had signed petitions saying… stop killing baby bears in distress.

The continued stalling of black bear rehabilitation in Nova Scotia is more than just an environmental issue—it’s an example of government dysfunction at its worst. A clear, safe, and cost-free solution was available on day one, but four years later, nothing has changed.

Why? Because bureaucratic survival depends on complexifying problems rather than solving them. Every study, every meeting, every additional delay justifies the existence of the people within the system. If the problem were solved, there would be no more jobs in managing it.

The Premier ordered it to be done. The people of Nova Scotia support it. The science backs it.

And yet, the machine grinds on, ensuring that simple solutions never see the light of day.

It’s time for Nova Scotians to demand an answer: Why is this still not done? And more importantly, who is actually in charge—the Premier, or the bureaucratic machine that defies him?

RELATED NOTES:

Estimating black bear populations in Nova Scotia—and elsewhere—is fraught with challenges because the methods used often rely on proxy data like harvest rates, car collisions, and nuisance reports. These numbers are influenced by human behavior and external factors, such as changes in hunting regulations, road networks, or urban expansion, which may reflect trends in human activity more than actual changes in bear populations. For instance, an increase in roadkill could just as easily indicate more cars or roads as it could a growing bear population. Without accounting for these external variables, such data risks misrepresenting reality.

The broader issue is that population estimates are often presented without context or an acknowledgment of their uncertainty. A single figure without confidence intervals or caveats creates a false sense of precision, leading to policy decisions based on incomplete or misleading information. To improve, methods must integrate multiple data sources—like genetic sampling and camera traps—while clearly communicating the assumptions, external influences, and statistical uncertainties behind the estimates. Without this transparency, population estimates risk becoming less about wildlife management and more about managing perceptions.

Nova Scotia encompasses approximately 55,284 square kilometers, with a population density of about 18.91 individuals per square kilometer. This suggests that a significant portion of the province remains sparsely populated or uninhabited.

While precise figures on unpopulated land are not readily available, it's noteworthy that forests cover over 80% of Nova Scotia's land area, totaling over 4 million hectares, 40,000 square kilometers or over 10 million Acres.

These forested regions, along with protected areas like the Tobeatic Wilderness Area—the largest protected area in the Canadian Maritimes at nearly 120,000 hectares—contribute to the province's uninhabited landscapes.

One local example... Anyone with a Google map or who has flown in to the Halifax airport can see an area of more than 100,000 acres unpopulated in the heart of HRM. It runs from Waverley to Musquodoboit Harbour, up to Meager's Grant, and over to the airport.

Given these factors, it's reasonable to estimate that a substantial portion of Nova Scotia's land remains unpopulated.

A black bear range varies by region but there's good support to say a black bear family can live happily in about 40 square kilometres.

The black bear rehab issue transcends the relatively small number of bears requiring care. As one of the largest and most iconic animals in the forest, black bears symbolize the health of our wild world and our relationship with it. They stand as a litmus test for how we, through our governments and institutions, choose to support—or neglect—our natural environment and the creatures within it. Their presence, and the challenges they face, reflect the broader mission and attitude of government toward conservation, wildlife management, and our shared responsibility for stewardship.

The Black Bear Population is Exactly What Nature Allows… Minus What We Kill

You don’t need any study to know the number of Black Bears in Nova Scotia.

It’s a wild animal in its natural habitat. All other things being equal, the number of bears is exactly the number that the ecosystem will support. No more, no less. It will vary based on weather, climate, and natural conditions and cycles. Exactly as it should.

But all other things aren’t equal. The number missing is the number killed by cars, hunters, and the government each year.

The population, whatever it is, is diminished by exactly that amount killed relative to what it would naturally carry and is forced to try and rebuild from there.

It’s only reasonable that those in a position to help should be allowed to do so at least to the degree that the animals are killed.

Supporting black bear rehabilitation is not just about helping individual animals; it’s emblematic of a broader commitment to coexistence with nature. It underscores the need for policies that balance human activity with ecological integrity, ensuring that our forests remain vibrant and sustainable. The bear’s plight speaks to the larger story of how we interact with our environment and whether we view ourselves as partners in preserving it or as indifferent occupants, or worse - harvesters of the forest as a commodity product where all the animals are treated little better than insect pests in a farm field.

Addressing this issue with care and purpose can inspire a shift in mindset, one that values our wild spaces and the interconnectedness of all life.

Dr. Martyn Obbard, a leading black bear researcher, provides a fact-based, science-backed perspective on black bear rehabilitation in the video. His key points can be summarized as follows:

1. Bear Rehabilitation is Safe and Effective

Scientific evidence supports the successful rehabilitation of black bear cubs and their return to the wild.

Studies show that rehabilitated bears do not become habituated to humans when properly managed.

Rehabilitated bears behave no differently than wild-born bears in terms of survival, territory establishment, and interactions with humans.

2. Bears Are Not a Major Threat to Public Safety

Black bears are naturally wary of humans and prefer to avoid conflict.

Attacks are exceptionally rare, and when they do occur, they are often due to unique circumstances, not inherent aggression.

There is no evidence that rehabilitated bears pose a greater risk than wild bears.

3. Other Provinces Have Proven Rehab Works

Provinces like Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, and New Brunswick have successfully run bear rehabilitation programs for decades without public safety issues.

These programs have tracked released bears, confirming that they survive well in the wild and do not cause increased human-bear conflicts.

4. Nova Scotia’s Black Bear Population is Small and Not Overcrowded

Claims that Nova Scotia lacks enough bear habitat or that rehabilitated bears would struggle for space are not supported by scientific evidence.

Black bears are territorial and solitary, and they naturally disperse to find their own space.

5. Government Fears About Bear Rehab Are Unfounded

Resistance to black bear rehabilitation often comes from misinformation and fear, not science.

Claims that rehab increases bear-human conflict or that cubs will become dependent on people are not backed by data.

The real issue is bureaucratic inertia, not a genuine wildlife management concern.

Black Bear Rehab is a No-Brainer

Dr. Obbard’s message is clear: Black bear rehabilitation is a well-established, scientifically sound practice that poses no significant risks to public safety. Other provinces and small states have done it successfully, and there is no rational reason why Nova Scotia cannot do the same. The refusal to implement it is not based on evidence—it’s based on bureaucratic hesitation and misinformation.

This is a very accurate summary of the obstacles to bear rehab in N.S. we are the only province in Canada without a protocol. For bear rescue and rehab. I have been both a hands-on wildlife rehabilitator and part of the federal regulatory framework for rehab. To put it bluntly, Nova Scotia has always been anti-rehab based on totally false reasoning. In Canada, well regulated wildlife rehab is seen as an important part of public education into natural resources management. Except in Nova Scotia. I once had a DNRR director describe wildlife rehab as just trying to make pets out of wild animals. The blatant ignorance of that remark has been the guiding principle here in Nova Scotia since day one. There are three classifications of wildlife here in N.S.: huntable; trapable; and nuisance.

Bears should be rehabbed and released in spite of government retardation and laziness. Enough people would protest if government stooges were sent to remove the animals.