Anger Is a Poor Architect: On Protest, Politics, and the Forgotten Power of Joining In

We’ve grown up with the idea that real change comes from protest—that confrontation is more authentic than collaboration, and standing outside the system is more honest than working within it.

Why Protest Alone Won’t Save Us: The Case for Joining Political Parties in a Fractured Democracy

We’ve grown up with the idea that real change comes from protest—that confrontation is more authentic than collaboration, and standing outside the system is more honest than working within it. But what if we’re wrong?

What if that belief, born in a noble time and nurtured by spectacle, has outlived its usefulness? What if, fifty years on, we’re mistaking noise for power and outrage for agency?

In this essay, let’s explore how direct action became the dominant political posture, why it’s failing us now, and how the quiet, often invisible act of joining is still the most powerful tool we have for building a better country. We’ll look back to the chaos of revolutionary Paris, to Greenpeace in Zodiacs, to modern online rage—and make a case for boring, beautiful democracy.

It’s been over fifty years since The Byrds sang “Wasn’t Born to Follow”—a line that became an anthem of generational defiance. The idea had been brewing in pop culture since the invention and rise of the teenager in the 1950’s. It echoed across anti-war protests, sit-ins, back-to-the-land communes, and every dropout dream from Woodstock to Waco. The idea was simple, seductive: you, too, are a rebel. You don’t owe obedience to broken systems. You are not meant to conform.

But here we are, half a century on, and maybe it’s time to ask—weren’t we?

Weren’t most of us exactly born to follow? Not in the sense of blind obedience, but in the deeper, quieter truth of social life: the world runs on cooperation, compromise, and interdependence. Every great movement needs its firebrands, yes—but it also needs a lot more record-keepers, committee members, editors, volunteers, and steady hands on slow levers. It needs people who aren’t storming the gates, but showing up—week after week, year after year—to build what comes after the revolution. Like fixing up those broken gates. How many leaders, rebels, and iconoclasts do we need? How does this whole thing work if we're all protestors? The budget still has to be balanced. The school still needs a groundskeeper.

That protester’s anthem—the heroic rebel narrative—has given us energy, visibility, and in many cases, real change. But when everyone thinks they’re the outsider, when every citizen is a critic, a dissenter, an iconoclast with no loyalty to the group, we lose something vital: the functioning middle. The people who do the long, slow work of democracy. When too many step out, exclude themselves, excuse themselves, what’s left inside is either captured or corrupted.

The truth is, most people aren’t born to lead or to break things. Most people are born to contribute—quietly, imperfectly, and in cooperation with others. And that’s not a flaw. That’s the miracle at the foundation of human flourishing.

Maybe the next anthem we need isn’t about not being born to follow.

Maybe it’s about the courage to join, to stay, to compromise, and to build. The future won’t be made by the loudest voices alone. It will be made by those who choose—consciously, humbly, and repeatedly—not just to beard power when no choices are left and urgency demands, but to take part in the long, wide path to the world of more and better that we can all imagine.

I often get accused, threatened, outed, and cancelled (literally, it’s the number one reason for subscription cancellations on Substack) for ‘bothsiderism’. Just this week I’ve been accused of being a Liberal hack, a Conservative Neo-Liberal, and a stinking NDP Film and TV person. And more generically, an ‘insider’. Which, in fairness, is probably closer to the truth of what’s happening here, but just not as nefarious as the condemnation would insist.

Of course, what’s actually happening here is a creed,

Sit down before facts with an open mind.

Be prepared to give up every preconceived notion.

Follow humbly wherever and to whatever abyss Nature leads, or you learn nothing.

Don’t push out figures when facts are going in the opposite direction.

Admiral Hyman Rickover

But, “people be writing” like,

I have read the book, obvs. The main theme of the book Values: Building a Better World for All is pretty much in the title — that market economies must be re-anchored in moral values to serve the public good, rather than allowing market forces to define value entirely on their own.

Carney argues that we’ve confused price with value, and this confusion has led to financial crises, climate degradation, and growing inequality. He calls for a reset of capitalism, where markets are guided by human values—like fairness, responsibility, and solidarity—instead of short-term profit.

But, is there any real point in responding with stuff like that? My experience is, it just makes people more cross.

Fifty years after Greenpeace’s first high-seas protest, the legacy of direct action lives on—but so does its unintended consequence: a whole generation that believes standing apart from politics is the only honest position. What if we’ve misunderstood where change actually comes from?

Zodiacs, Killers, and Green Peace

As the large Soviet factory ship, harpoon gun poised to fire, loomed over a whale immediately below the bow, Rex Weyler struggled with his camera fighting wind, waves, the stench of the Soviet harpoon ship, and the migraine sea sickness only those trying to focus an eye through a camera while being tossed by the sea can know.

A Line in the Water

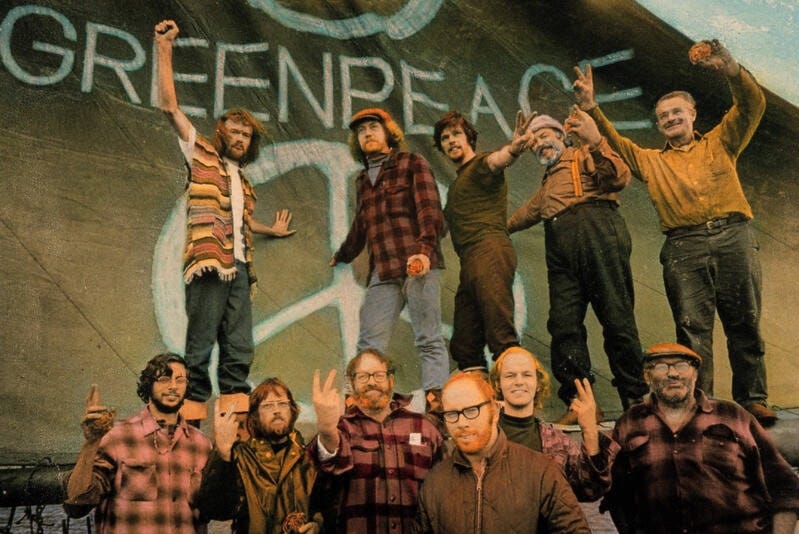

Fifty years ago next week—late June 1975—the fishing vessel Phyllis Cormack slipped out of Vancouver carrying a small band of activists and old Zodiac inflatables determined to confront Soviet whaling ships operating off California. The mission, dubbed Project Ahab, was Greenpeace’s first direct-action campaign against whaling. On June 26 and 27, they placed themselves between the harpoon guns and the whales. At least once, a harpoon was fired over their heads. The images were electric. Men in Zodiacs, bobbing in cold Pacific swells, facing down the industrial mechanized slaughter of the sea.

It made headlines. It made history. And it made a generation believe that change came from confrontation.

But there was something else in those pictures. Something we didn’t see at the time. Something we’ve been living with ever since. It’s not democracy. Not even close.

The Direct Line to Government That Wasn’t

What Greenpeace—and all that followed it—offered was a feeling of agency. Protest felt pure. It felt righteous. It didn’t require compromise, bureaucracy, or boring Tuesday night meetings in drafty church basements. It said: you can make noise and make change.

But here’s what we didn’t see coming. Direct action became the only action many people ever took.

Not as a stepping stone. Not as an entry point to civic life. But as an endpoint.

It created a generation of citizens who only speak to their government when they’re mad. Our politicians and our bureaucracy are in the business of dealing with folks who are angry and self-interested. They’ve become expert at it. And that’s a bad thing. A large swath of the politically active only engage with the community through opposition. It’s been the main track for 50 years now. The claimed successes are many, though seldom celebrated because the focus is on what’s wrong, not what’s fixed or getting better. We began to see mainstream political parties, municipal councils, even neighbours with a different lawn sign, not as fellow citizens—but as adversaries.

In a strange way, protest replaced politics.

And spectacle replaced structure.

The Strange Secret Success of the Environmental Movement

Most people on the planet today live better, healthier lives because of the great successes of the modern environmental movement. It’s at the top of humanity’s greatest modern accomplishments… and that is saying something. So why don’t we talk about it?

Rage as Identity

Spend five minutes online. The loudest voices are almost never members of political parties. They are critics of parties. They are critics of government. Critics of process. Of compromise. Of each other.

Ask them how they want change to happen, and the answer is always opposition, angry, and emotionally pure. No deals. No work. No votes.

They don’t believe in joining. They believe in “calling out.”

They don’t believe in dialogue. They believe in exposure.

And if we step back just a little and look, a strange truth emerges: they don’t believe in democracy as a practice. Only as a feeling. Something you express, not something you do.

Why Joining Still Works

Here’s the boring truth: political parties—yes, the ones with logos and imperfect leaders and compromise platforms—are still the best route to real change in Canada.

Not because they’re perfect.

But because they’re porous.

Any Canadian citizen can show up, knock on a door, attend a riding meeting, submit a resolution, run for delegate, or help pick the next leader. You can be a nobody, a stranger, a newcomer, a kid with a good question—and the structure will hold the door open, even if just a crack. If you push, it opens further.

And yet... almost no one does this anymore.

Even as more and more people scream that they’re not being heard, fewer and fewer are willing to speak the language of action: engagement, votes, memberships, coalitions.

Joining something is now seen as selling out.

That’s the real legacy of protest without purpose.

The Irony of City Hall

Of course democracy is run by the radical fringe, because normal people have stuff to do.

The irony here is that with the continued rise of protest as politics things keep getting quieter at the ballot box, in the parties where real decisions are made, and down at city hall.

Voter turnout continues to decline, especially among people who will be around the longest and should care the most.

Parties are so small now, that they are ripe for coups and takeover by any organized group with a couple hundred or less real supporters. Of particular note, the Liberal Party of Nova Scotia, the natural governing party in the historic sense, probably doesn’t have enough passionately engaged active members to take on a Little League team if the kids choose to vie to run the province instead of the diamond. And the federal Conservative Party is in an existential crisis, and an easy target for any interested progressives who might like to retake the political middle.

And down at city hall council and its processes are stifled, stuck, and hidden away such that no normal citizen with stuff to do could ever follow closely enough to get a sense of, let alone influence what is going on.

But democracy can and should be loud, even without the direct action, protest, burn it all down, consultation veto industrial complex contingents going off like a box of birds.

SIDEBAR: We Always Have Paris

If you think modern politics is messy, try Paris in the 1830s. If we want to see what government by direct action and burning it all f#@king down looks like, picture Paris in the summer of 1832.

The French invented the word revolution, then couldn’t seem to stop having them. From 1830 to 1871, France cycled through two kings, two emperors, two republics, and one bloody commune uprising. In the span of a single lifetime, Paris went from monarchy to liberalism to fascism to democracy to chaos and back again.

It was a time when Victor Hugo wrote Les Misérables not as a romantic tragedy but as a dispatch from the streets. Hugo himself manned the barricades in the 1832 June Rebellion—yes, the one in the musical. And when he wasn't fighting, he was exiled for talking too much about liberty.

Chopin was coughing blood onto his piano and regularly ate hay because only the richest could afford fresh food. Pandemics raged and left bodies in the street. Everyone who could was leaving - some from fear of cholera, others from fear of revolution. The rest were not listening to Chopin. Beset by financial worries, health horrors, political upheavals and war, they partied at all night pleasure palaces and dance halls, where in in fancy dresses and cartoonish suits — most of them grotesque and satirical— the balls were kept up till seven in the morning with drinking, drugs, and sex, and all the extravagant gaiety and noise and fun with which the French people managed such matters. There was even a popular cholera-waltz and a cholera-gallopade.

The plays and stage shows of the Boulevard du Crime reflected more closely the values, experiences, and news of the day in Victorian Paris than even our own pop culture today reflects ours.

A noted magazine writer, Nathaniel Parker Willis, investigating the scene, reported, “As if one plague was not enough, the city is all alive in the distant faubourgs with revolts. Last night the rappel was beat all over the city, and the National Guard called to arms and marched to the Porte St. Denis and the different quarters where the mobs were collected. The occasion of the disturbance is singular enough. It has been discovered, as you will see by the papers, that a great number of people have been poisoned at the wine-shops. Men have been detected, with what object Heaven only knows, in putting arsenic and other poisons into the cups and even into the buckets of the water-carriers at the fountains. Several of these empoisonneurs have been taken from the officers of justice and literally torn limb from limb, in the streets. Two were drowned yesterday by the mob in the Seine, at the Pont-Neuf. It is believed by many of the common people that this is done by the government, and the opinion prevails sufficiently to produce very serious disturbances. They suppose there is no cholera, except such as is produced by poison; and the Hotel Dieu and the other hospitals are besieged daily by the infuriated mob, who swear vengeance against the government for all the mortality they witness.”

Over in the cafés, George Sand—pen name of Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin—smoked cigars, wore men's clothing, and published radical essays that made her a literary and political sensation. She wrote love letters to Chopin and open letters to the National Assembly. The new Romantic movement combined with the suffrage movement to mark an irreconcilable battle line between the sexes on issues from the morality of marriage to the legitimacy of Queen Victoria.

Meanwhile, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (yes, nephew of the Napoleon you're thinking of) was elected President of the Second Republic in 1848, promising reforms and progress, with overwhelming public support… then declared himself Emperor three years later and dissolved parliament at gunpoint.

That’s populism, folks.

For every idea about freedom, there was a general with a musket. For every movement, a crackdown. The army shelled entire neighbourhoods of Paris in 1848. Journalists were imprisoned. Newspapers burned. Exiles filled the ships to England and the colonies.

But then…

Out of that noise came the modern French state. Civil code. Universal suffrage. Public education. A sense that the people could speak, could vote, could act—without necessarily burning it all down. What came from it was a modern, boring democracy and bureaucracy that we would all now easily recognize. It took half a century of lurching failure, egotism, and idealism, but by the 1880s, France had a functioning Third Republic. It has survived the storm of populism, more wars, and the seduction of strongmen.

Why does this matter?

Because it shows that democracy—the real kind, with all its slog and compromise—is the goal, not the problem. A negotiation between power and people. It’s an argument we have with ourselves about the shape of things to come, and it is, by definition, never settled. Democracy is a long, wide road where few people get their way in the short run and everyone is better off in the long. It’s not a place for the impatient, angry, or egotistical. And when direct action, of any political stripe, tries to replace it altogether, the results tend to be violent, brief, and tragic.

Paris had barricades. We have comment sections.

But it’s still better to argue, compromise, and lose sometimes than to burn the whole thing down.

The High Cost of Standing Apart

Democracy isn’t a product. It’s not a service you review on Yelp. It’s a practice. And like any practice, it requires repetition, patience, and occasional failure.

It’s a negative feedback loop. Citizens can’t come in late to the process and expect it to get anything but worse. Democracy doesn’t work without active, everyday citizen participation. We have election cycles. And like all things circular the election is neither the end nor the beginning of the process of democracy. It’s just one tiny part of it.

We got tricked, somewhere along the way, into thinking that not participating was a virtue. That detachment was clarity. That purity was power.

But detachment doesn’t build schools, steward woods and waters, or produce renewable energy.

Only joining does that.

Only people who show up get to write the plan.

Coming along later and demanding ‘consultation’ is not democracy, it’s a con.

We gotta take the ‘con’ out of consultation.

Building Is Harder Than Breaking

It’s easy to tweet. Easy to protest. Easy to rage against the wrong government, the wrong policy, the wrong Premier or Prime Minister.

What’s hard is picking up the phone, attending the meeting, joining the party, finding allies, debating your position, losing the vote, showing up again. For years unending.

But that’s how change actually works.

Real leaders don’t appear from nowhere. They are shaped by the citizens who show up early, and stay late. We have to make the future—brick by boring brick.

Anger may light a fire. But it can’t build a house.

Attention, excitement, action are all awesome… in the moment. But nations are not lived in a sultry summer.

For building nations, you need people willing to work together—even with people they don’t like. Even with people they once protested. Democracy is work done with people you differ from profoundly in mind and manner. It’s not done as a battle. It’s done as a personal challenge to your capacity for understanding, compromise, and ability to think about a very complex, very long, process toward goals bigger than any of us can imagine — prosperous nations in a peaceful world.

I'll keep this short and sweet.

Better to affect change within the system than try to completely change the system itself.

I'll give you my real world example.

In 2003 in my last Environmental Science seminar at Dalhousie the graduating class was asked how they as individuals would use their education in the real world. What are your plans after graduation? Where would you like to work?

One by one every single student said they would prefer to work for Greenpeace or Ecology Action Center. It was what they were taught was the "right answer".

When it finally came around to my turn and as a mature student, single parent I told them all I would like to go to Alberta and work for one of the large oil producers there.

There was so much shock and anger that some actually stood up arms waving.

When the crowd finally stopped attacking me the professor asked me why.

I answered calmly that I felt that's where I could affect the most change.

Within the system! I hoped to be able to use my knowledge to help them become a better company with respect for the environment.

Silence.

No debate. Just shock.

I will never forget what that taught me.

The education system is flawed and it's gotten much worse. I hope some of the students in the room took that with them as well.

Cheers JW. Keep on keeping on.

I don’t always agree with you on your takes but when I don’t my impulse is to add to the discussion and I secretly want to buy you a beer and talk further about what you have written lol! It is the nature of social media to get the kind of troll-like responses you have had, unfortunately. Best to just ignore them.

On this topic I am in general agreement. I am a member of a political party and volunteer during campaigns. I have joined our local community organization to help plan and volunteer for events. Democracy requires engagement to be successful.

Democracies are not inevitable though and can become corrupted as we are seeing in the US—a long slide toward authoritarian governance greased by too much money in politics.

In our (mostly) well-functioning democracy in Canada, we still do not do a good job of representing all points of view in parliament due to the “first past the post” voting system. When there is no representative voice in government the only path to be “heard” is protest.

I think where we are at right now is that far too many people feel alienated from politics generally and would rather criticize than participate. Social media feeds this and amplifies division for clicks.

Turning off our screens would be the greatest act of protest and maybe we would connect more with each other as a result.