A High-rise Isn’t A Neighborhood

The Urban and Up scam: They build the box, we build the rest—and foot the bill forever. Taking an honest look at the hidden public cost of Halifax's high-rise development ideology.

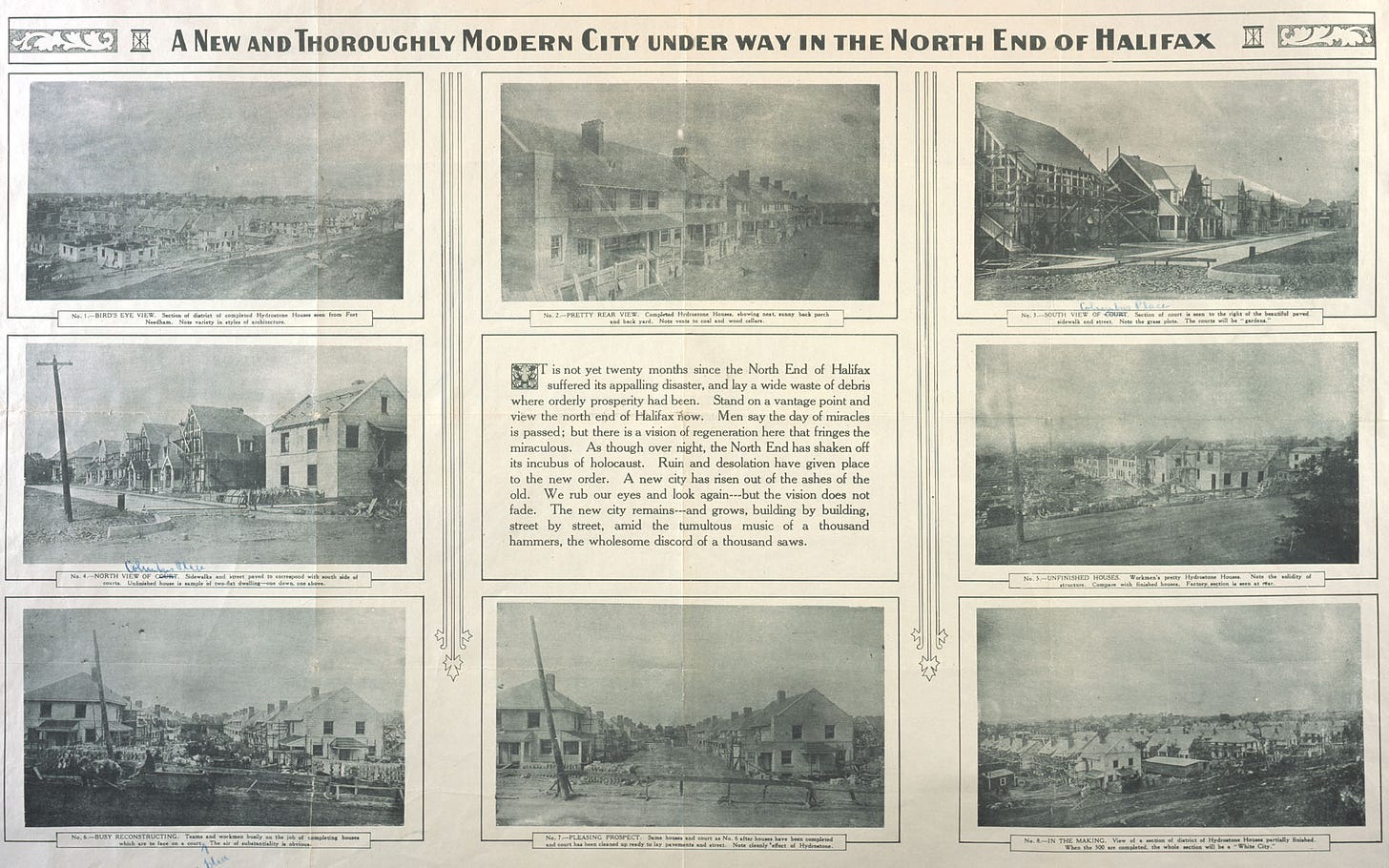

The horrible explosion’s scars looked even worse in the spring mud. But rebuilding had begun. In the summer of 1918, a man named George Ross completed his report for the 23 acres known as the Merkelsfield project.

It was his intention that the development of the 324 housing units, with sixteen shops and offices on West Young Street, should serve as a model of modern construction. His goal was to maximize the aesthetic qualities of the development and provide fire-resistant and sanitary buildings at a reasonable cost. He decided on hydrostone for the exterior of the houses. Hydrostone consisted of a mixture of gravel, crushed stone, sand, and Portland cement molded under pressure and finished with crushed stone that would give it a strong and handsome look. To provide variety, he designed six different types of four-unit buildings, as well as a variety of two-unit houses at the end of the terraces. He also altered roof designs and the arrangement of timber and stucco, in order to give buildings an individual appearance.

The spirit of the idea was captured in an illustrated poster, entitled "A new and thoroughly modern city under way in the north of Halifax."

The poster described the hydrostone construction as beautiful, neat, sunny, clean and substantial, and in glowing terms it encouraged people to:

Stand on a vantage point and view the north end of Halifax now. People say the day of miracles is passed; but there is a vision of regeneration here that fringes the miraculous. As though over night, the North End has shaken off its incubus of holocaust. Ruin and desolation have given place to the new order. A new city has risen out of the ashes of the old. We rub our eyes and look again — but the vision does not fade. The new city remains — and grows, building by building, street by street, amid the tumultuous music of a thousand hammers, the wholesome discord of a thousand saws.

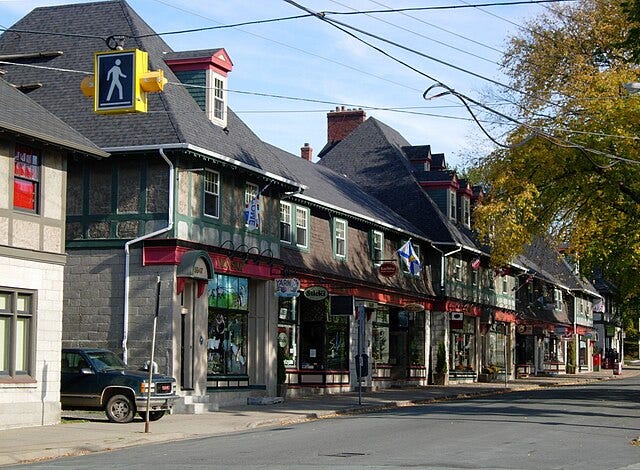

More than 100 years later the Hydrostone district is among the most iconic and valuable communities in North America.

If you bought, as any individual could, one of these little houses 100 years ago, you would have earned a return of over 10,000 percent. In fact, that windfall profit has been mostly shared over generations of regular working Halifax families who lived and raised children in those homes, and today the descendants of those families, now in their many thousands are the inheritors of that legacy.

Let’s compare and contrast the broad economic and social view of this iconic city development with the economic and social impact of the ‘urban and up’ ideology of the current ‘visionaries’ at the city hall.

The Hydrostone, Halifax. High-density, high-efficiency, urban housing for over 1,200 people with all walkable amenities, green spaces, and services built in less than two years, is now more valuable than ever to families, to the city, and to the future, over 100 years after it was built.

We all know what a nice home, a nice street, a nice neighbourhood looks and feels like. No one is confused. We know simple homes built with sustainable local materials, and workers of average skills, can be built quickly, inexpensively, and safely built to last over 100 years while increasing in value (and taxes paid) consistently while adding to the city's infrastructure, assets, charms, and value. We can literally see it incarnate in the city’s Hydrostone Northend.

We also know that, once built, they can be upgraded as needed and as affordable to embrace changing styles, uses, and technology. We know that neighbourhoods and towns built this way in similar climates in European centres have stood for hundreds of years and just get more beautiful and valuable with time.

The only question is why aren't we building like this? Why aren't we creating the kinds of places the luckiest among us save and scrimp to go on holidays just to stand in for a few days? Why don't we build the towns that people are waiting for? Or better yet why don't we restore the dozens of towns and villages from Amherest to Canso that we've let fall into disrepair as we put all our eggs (and people, and businesses, and services) into the basket of Halifax. Why are we taking a 'first little pig' approach to development and letting our city growth be a cost - a net drain on our wealth - rather than a valuable investment in the rising generation before us?

The Hydrostone district in Halifax is one of Canada's best-kept urban planning success stories, a living testament to the principles of human-scale design, resilient building, and the timeless wisdom of creating communities that people love. Born out of disaster—the 1917 Halifax Explosion—it stands today, for all to easily see, as an example of what urban planning should be striving for, yet so rarely does.

For over a century, the Hydrostone has thrived and steadily increased in value, love, and respect. Why? Because it adheres to the principles that people inherently recognize as good. It is walkable, beautiful, efficient, and human-centered. Streets are lined with sturdy, handsome homes that share a consistent design language but allow for individual expression. There are green spaces, a small but vibrant commercial core, and a sense of place that is impossible to fake.

The Hydrostone stands as proof that high-density housing does not have to mean soulless towers or endless sprawl. It represents a human-scale, livable, and complete neighborhood—an antithesis to today’s “Urban and Up” development mentality, which prioritizes raw density over community, ignoring both historical wisdom and the actual desires of the people who live in these spaces. Worse, this approach shifts the burden of building a real, functioning neighborhood onto everyone else.

A tower maximizes developer profits but externalizes all the costs. That’s not planning—it’s a Ponzi scheme.

The "Urban and Up" model thrives on a sleight of hand: it boasts tremendous density, but only by ignoring all the essential spaces that make a city livable. It designs only for the box—the private, rentable square footage—while offloading the need for parks, schools, gathering places, amenities, and livable streets onto the city, taxpayers, and future residents. The result is an illusion of efficiency that collapses under scrutiny.

The Hydrostone, by contrast, was designed as a complete community. It achieved the highest possible density while still allowing for a rich, walkable, and dignified way of life. It balanced private and public spaces, individual homes and shared amenities, streetscapes, and green spaces, in a way that still works over a century later. The big-box tower model, on the other hand, strips these elements away, forcing residents to either buy back what should have been designed in from the start, or simply go without. Or worse, it forces the rest of us to pay for it.

Look, everyone knows something is wrong. Imagine life if you lived in a 21st-floor apartment without a bathroom. People are resilient. You could do it. Find a way. Maybe use chamber pots to pee in the night. Plan your BM’s for work. Buy a spa membership to shower and keep clean. But it would be awful. The current state of affairs is no different. You have the bathroom, but you lack other basic amenities of community life. A high-rise apartment building is not a neighbourhood. At least not the one we’re dreaming of. Who pays for the rest if the developer systems has extracted all the wealth? How does the neighbourhood get built, survive, and thrive, beyond the box in the sky? It does’t. Growth without prosperity feels awful because it is awful. And it’s worse for the demoralized rising generation looking to the future with unseeing eyes. If they can’t imagine a better future, there is no better future.

When all the missing pieces are accounted for, the truth becomes clear: the "Urban and Up" model isn’t just socially corrosive—it’s economically inefficient. It shifts costs, degrades quality of life, and leaves future generations with a built environment that doesn’t work. The Hydrostone proves that good urban planning isn't about stacking people into higher boxes; it’s about shaping spaces that serve human lives.

Look at the real estate market. People pay a premium to live in the Hydrostone. Families choose to move there because it offers something modern developments do not. Planners talk about the need for high-density housing, but the market has already spoken—people want to live in human-scale communities that feel like home, not just exist in vertical stacks of rental units.

In Christopher Alexander’s The Timeless Way of Building, he argued that the best places are ones that grow organically and respond to the way humans actually live. The Hydrostone embodies this principle. It was built quickly, with modest materials and straightforward techniques, yet it has lasted a century and only grown in value. It follows the patterns of traditional towns in Europe—places that have been continuously inhabited, cherished, and maintained for centuries.

Contrast this with the current development trends in Halifax and beyond. The "Urban and Up" mentality pushes towers, maximizing the number of units on the smallest footprint possible. It prioritizes density over livability. This approach is being sold as progress, but it ignores the first lesson of economics, as articulated by Henry Hazlitt: good economics requires looking at both the short-term and long-term effects of any policy, not just the immediate gains. Building massive rental towers may seem like a quick fix for housing demand, but does it create lasting, desirable communities? Does it allow families to build equity? Does it generate wealth that circulates locally? Or does it simply funnel money into large developers and corporate landlords, at the expense of a livable city? The answer is painful and obvious.

We know what people actually want. The evidence is everywhere. The Hydrostone remains a dream neighborhood. Disney spends billions recreating small-town main streets because people who crave that aesthetic and experience will pay premium money just to imagine it. Vacation destinations across Europe charge a premium just to stay in neighborhoods that function the way Hydrostone does. The question isn’t whether we know how to build great places—we do. The question is why we are refusing to do it.

Nova Scotia is uniquely positioned to reject the failed urban planning trends of larger cities and instead lead the way in smart, human-scale development.

Why should we force more and more people into Halifax when we have an entire province full of towns and villages that could be revived and made desirable again? Why let small communities from Amherst to Canso wither while pouring resources into making Halifax denser, more expensive, and ultimately less livable?

We are building as if we’ve learned nothing from history. The Hydrostone proves that we can build quickly, affordably, and beautifully. It proves that urban density and livability are not opposites. It proves that people will pay more for good design. It proves that walkability, green spaces, and community cohesion make a neighborhood resilient.

The only thing left to prove is whether we have the courage to stop the mistake we continue to make, and start again in the direction we know is right. We shouldn’t stick with a mistake just because it cost a lot of money and we spent a long time making it. That is the road to ruin. Even the most petulant driver sometimes has to admit at some point they’ve taken a wrong turn.

The current path is written in the city’s skyline. It’s one of sadness, despair and resignation that would rival any brutalist Soviet era regional city panel buildings. Worse. Even the Soviet panel blocks are limited to five to seven stories. That would be a transformational improvement to the Halifax Plan.

I’m here to tell you we don’t have to give up or give in. We don’t have to accept what is. We can imagine more and better. We can sweep away what is. We can start again with a new goal in mind. And we can create more wealth for ourselves and Nova Scotia’s rising generation than our history has ever imagined in doing it.

Reminds me of the brilliant piece decades ago by the funny guy PJ O'Rourke about his trip to the Soviet Union and the horrible architecture, the cheap concrete apartment buildings where from the ship on the river you could see the absence of straight lines, a metaphor for Stalinist central planning .... a kind of anti-travel piece, like Christopher Isherwood in Berlin in the 1930s...

I agree 100%, I was envisioning a similar community being built in the Cogswell exchange district but sadly Council wants 30-40 story high rises there instead. These were not depicted in the video that was made to show what the new district would look like.